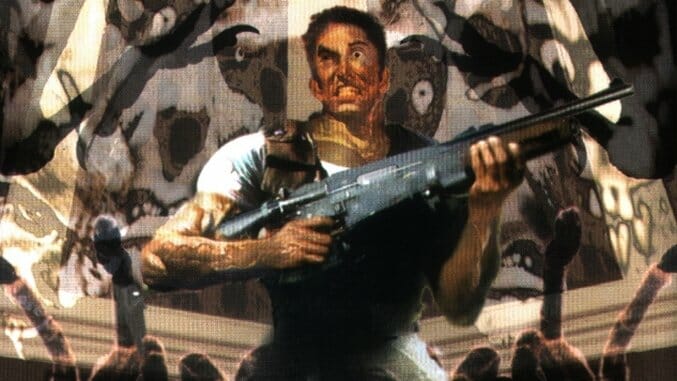

Why the Original Resident Evil Remains Relevant 20 Years Later

Twenty years ago today, when Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men’s “One Sweet Day” was ruling the music charts and the Coen brothers’ Fargo had just hit theaters, a new game lurched onto PlayStation, its dead hands outstretched for our brains… and, well, our cash.

Resident Evil was a smash hit from virtually day one, and it’s easy to see why: it combined the brain-teasing puzzles of point-and-click adventure games of the 1980s and ‘90s with a healthy dose of real-time action. It wasn’t the first horror game but, just like Halloween wasn’t the first slasher movie but kick-started the slasher genre, it was the first game to convince large numbers of people that horror—and, more specifically, survival horror—was its own bankable genre.

The creation of a late twenty-something developer called Shinji Mikami, work on Resident Evil began in early 1994. In a somewhat unlikely leap, Mikami was then best known for his Disney game adaptations, including successful titles like Aladdin and Goof Troop for the SNES. The horror game Mikami settled on making was a loose update of Capcom’s Sweet Home, a 1989 RPG title in which five characters are trapped together inside an abandoned mansion by the vengeful ghost of a woman who died there years earlier. From the excellent Sweet Home, Mikami borrowed the claustrophobic setting, the iconic “door opening” animations, the focus on puzzles, and (most essentially) the emphasis on survival. All of these were updated for the new generation of videogame consoles released in the mid-1990s, in this case specifically Sony’s new Playstation console.

Stop! Don’t, Open, That, Door!

Of course, looking at the original Resident Evil from the vantage point of 2016, what is notable is not so much the game’s “next gen” capabilities, but rather what it managed to pull off with limited technical firepower. Much as the smartest horror movie directors compensated for laughable effects and silly premises by relying on audience’s imagination, Mikami and his team took what could have easily been technical shortcomings and turned them into advantages. For instance, early on, the team was forced to ditch its dream of using fully 3D graphics in favor of pre-rendered backdrops with static “camera” shots. Rather than this being a weakness, however, Resident Evil opted for impossibly Hitchcockian camera angles which left players in a constant state of paranoia about what was lurking just out of frame.

Much the same can be argued about the cumbersome control system, which some gamers point to as a weakness of the original Resident Evil. Was it as fluidly smooth as a game like Quake, the other big title that gobbled up my time during the summer of 1996? No way. Did its dodgy controls, which had the on-screen characters rotate on their axis like particularly skittish tanks, make you panic even more when a zombie was lumbering after you? You bet. Resident Evil’s controls were the gaming equivalent of one of those nightmares where you’re running from some unseen threat, but your limbs just won’t do exactly what you want them to. I’m not sure this was entirely the point—but it certainly worked.

The least defensible aspect of the game is its terrible dialog. When they’re not creeping around the game’s dilapidated mansion, which comes straight out of The Shining, Resident Evil’s characters participate in some of the most hilariously naff conversations to ever make it into a professional title. Worse than just “clunky,” Resident Evil’s script sounds like it was run through a dozen languages in Google Translate before being translated back into English and given final approval. How else to explain the immortal lines, “That was too close! You were almost a Jill sandwich!” or “Don’t be a hard dog to keep under the porch, Barry?”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-