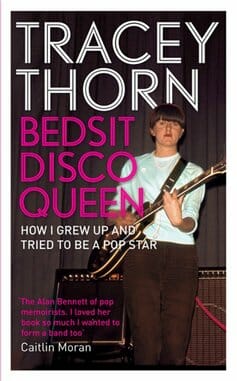

Bedsit Disco Queen: How I Grew Up And Tried To Be A Pop Star by Tracey Thorn

Like The Deserts Miss The Rain

Books Reviews Tracey Thorn

Why don’t we get more books from female pop musicians?

It seems every aging male rocker throws together a volume—in the last year, we’ve heard from Pete Townshend and Neil Young, in addition to several more entries in the never-ending annals of Mick and Bruce. Similar tomes from the ladies in the business show up far less frequently. Of course, women must battle the cumulative sexism of two entertainment industries, music and publishing, so maybe it’s lucky that we get any of their stories at all.

Bedsit Disco Queen, by the English artist Tracey Thorn, arrives as one of these rare, shining examples of musical autobiography—or, really, autobiography in general.

Thorn helped found two groups in the post-punk years of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and these anticipated several subsequent developments in popular music. Much of the hazy guitar-pop that’s made in the “indie” world these days owes some debt to Thorn’s first group, the Marine Girls. New bands that favor slinky ‘80s-inflected R&B (the recent album from Rhye, for example) walk a path Thorn helped chart as a member of Everything But The Girl (EBTG). Thorn’s groups offered a nice course in startup-do-it-yourself independent success in the days long before Kickstarter, and EBTG showcased the merits of constant artistic reinvention.

Oh, and Thorn’s bands also claim their share of good and commercially successful music. Thorn notes that she’s sold about nine million records in all, a remarkable accomplishment for any recording artist. It’s especially impressive considering that Thorn claims her groups “existed mainly on the margins.”

Thorn’s early work with Marine Girls consists of a few strummed guitars, hardly plugged in, no songs longer than 2:30, these with rudimentary percussion and harmonies—simplicity as beauty. Taking this to its extreme resulted in Thorn’s first solo effort, the Distant Shore mini-album. We hear just Thorne’s guitar and a series of melancholy, precise songs about feelings people rarely voice…and struggle to describe. The overly excitable English magazine NME wrote that Thorn existed “midway between the Shangri-Las and Nico,” though really she doesn’t share much with either of these artists, besides gender (and Thorn plays an affecting cover of “Femme Fetale,” which Nico originally helmed).

Then Thorn changed pace, hooking up with Ben Watt to form EBTG. She describes the group as “in the charts, out of them, then back again…signed, dropped, re-signed, mixed and re-mixed.” Maybe you love that group for “Each And Every One,” an early hit. The tune cleverly links the gently relentless groove of bossa nova—strengthened by a horn section—with a frank discussion of flawed romantic interactions. It’s as if the only place the song’s subjects could talk about their feelings happens to be in the middle of a crowded club, where they gain enough confidence (by performing impeccably choreographed dances moves) to say things like, “Being kind is just another way to keep me under your thumb, and I can cry because that’s something we’ve always done.”

Many prefer the second EBTG album, which emulates the spit, polish and jangle of the group’s then-idols, The Smiths. The American crowd might have checked in for The Language Of Life, a 1990 album recorded in the U.S. with the best R&B studio musicians (including the drummer Omar Hakim, recently drafted by Daft Punk to add that human beat to its music).

Thorn also got noticed for her work with another group, Massive Attack, which drafted her to sing on its second album, Protection. Finally, anyone who has spent fun times with the Ultimate Dance Party 1997 CD knows Todd Terry’s galloping remix of “Missing,” with its memorable refrain, “I miss you, like the deserts miss the rain,” a million-dollar lyric that should have hit charts a lot earlier. Not every iteration of EBTG had the same vitality, but to its credit, the group never stayed in one place for long.

Thorn’s voice and her love of smart, straightforward lyrics, usually about love and the pain it can cause, solely connects all these musical endeavors and entities. She sings fairly low and clearly, and she’s confident enough to know that volume does not always mean strength. Critics often describe her voice as sultry or smoky, though she rarely sings come-ons—she sounds like the type more likely to drink a couple glasses of wine and hit the hay than stay up all night smoking cigarettes.

In the world of pop, where people love hidden meanings and obtuse references, Thorn’s candor often arrests. If she’s hurt, she’ll say so. If she shouldn’t be hurt but is anyway, and she needs you to deal with it, she’ll tell you that too. Romance, like pop music, involves performance; sometimes it doesn’t pay to play all the cards up front. Thorn cuts through games, and listening to her costs much less than a therapist. But she doesn’t annoy or preach. After all, she doesn’t have it figured out either. If she did, she probably wouldn’t feel the need to write as many songs.

Thorn writes in Bedsit Disco Queen about her disparate influences, ranging from Watt’s love of jazz and Kevin Coyne to her appreciation of the Smiths, Dusty Springfield’s In Memphis album and country/Sun Studio artist Charlie Rich. She also provides an easy thread connecting all the music she listened to: “It was all about trying to piece together a kind of lineage of classic, simple songwriting, no matter where or when those songs had been written.”

Thorn writes in a classic and simple style herself…and she’s got a knack for description. Telling about going to shows in the late ‘70s, she remembers “the grubby grottiness of it all,” evoking the unkempt filth of a dive bar in a few precise words. She throws around phrases like “emotional fuckwittery,” and suggests the Marine Girls sounded like “a class of year five children let loose.” Effective writing. To the point.

Thorn speaks truth to her fears as a woman in the male-dominated world of pop and to the criticism her music has received. The Marine Girls lasted just a short time at least partially because Thorn thought their loose, bedroom-sounding style pandered “to patronizing expectations of female musicians to remain” at what she calls a “shambolic level.” She’s also not shy in this book about addressing those who labeled EBTG as “jazz-tinged soft-rock background music for bed wetters.”

Finally, Thorn writes frankly about the way she approached one of the most difficult tasks in the world, artistic creation. When it came to making Eden, the first EBTG album, Thorn and Watt made five rules. “[N]o snare drum, which was too rockist. Only rimshot. . . no electric bass guitar; had to be double bass. . . no acoustic guitars, as they meant Folk music. . . no piano, which meant ghastly 1970s rock ballads. . . and no backing vocals—too glossy.”

Many autobiographies can be a slog. They force a reader to watch while the author tries to imbue the most mundane details of his or her life with cosmic significance.

Thorn is funny. She writes self-mocking lines about her teenage self going to anti-fascism rallies both “to see loads of bands. . . and stop the Nazis, all in one day.” One of her best sequences comes terse as Hemingway but far more amusing: “I want a baby. . . Ben doesn’t want a baby. We get cats instead. It’s not a great idea because a) I am allergic to cats, and b) one of them is mental.”

English-isms litter the book. I found myself completely lost when Thorn told her readers, “if at this point it all sounds a bit Enid Blyton, it was about to get a bit Irvine Welsh.”

Still, I was happily lost.

Elias Leight is getting a Ph.D. at Princeton in politics. He is from Northampton, Massachusetts, and writes about music at signothetimesblog.