There’s No Time Like the Present to Get Onboard with the Real James Acaster

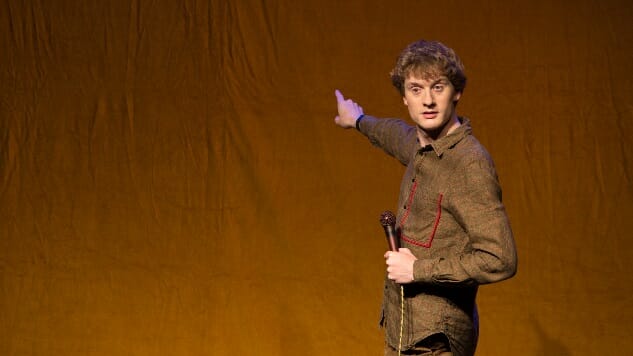

Photo by Silviu Nutu Vegan Joy Comedy Features James Acaster

Heads up: James Acaster is, pound for pound, as great a working comedian as you can find today. The British comic and storyteller got a big boost in America after Netflix released four of his specials concurrently under the title Repertoire. Those same shows had been critical hits for years prior to that, which was no doubt a major factor in releasing all four at once—a not-particularly-un-taxing move for Acaster’s considerable work ethic. “We filmed all four of them in a day,” he says, wearily. “I was walking off stage and sitting in my dressing room with my head in my hands.”

This isn’t especially surprising, considering everything he had going on. Acaster’s newest show, Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999, gets significantly more personal—though, a defining feature of Repertoire was his ability to make absurd situations grounded and emotionally resonant. When Acaster, in character as a cop whose ‘wife’ left him once he got too deep undercover with a group of criminal stand-up comedians, asks us, “What if every relationship you’ve ever been in, is someone slowly figuring out they didn’t like you as much as they hoped they would?” It elicits both laughter and existential moans from the audience. Cold Lasagne reverses this, finding the absurdity in Acaster’s real-life struggles instead.

While we can’t—and wouldn’t want to—spoil any of the jokes and stories at play here, in broad strokes: Acaster had a rough 2017. Dumped by his girlfriend, dropped by his agent and in a severely depressed state. Worried about drowning the show in stories of his own isolation during the writing process, he decided to take a different tact. “I wrote down all the times in my life when I’d felt most connected to people,” says Acaster. “Most of them aren’t in the show now. I wrote them down on paper and would take that to gigs, and realized they all happened in 1999.”

Balancing nostalgic memories of eclipses and historic football wins was a major necessity for Acaster during 2017. “I couldn’t get onstage and pretend that everything was fine,” says Acaster. “The year I filmed those specials, I toured them all, and that took most of the year… I had done that kind of comedy so relentlessly.” What allowed Acaster to blow off some steam was the book tour that immediately followed the pre-Netflix run, giving Acaster the chance to tell refreshingly true stories and figure out a new approach for himself.

What I am very pleased to report is that in the transition to this more personal material, Acaster nimbly avoids the pitfalls that trip up most other comics who turn their focus to their own lives. It is neither self-pitying nor particularly self-hating—despite the title—and Acaster is smart enough not to shoot himself in the foot when it comes to his greatest strengths. Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999 is chock full of the extreme escalations that he specializes in. He’s found a way to identify the natural escalations in his own life better than almost anyone (I’ll just say, you’ll never guess who his ex left him for…)

This apparently wasn’t always the case, though, and much of Acaster’s new voice was found through a painful trial by fire. “In shows where I’m talking about made up stuff that’s not true, if a joke about a honey company isn’t working, you kind of still believe in it, and it’s fine,” he says. “You know that you want to talk about that onstage. You know that you want to make a joke about a honey company. You know that you’re just getting the mechanics of it wrong. When you’re talking about a really horrible personal thing that happened to you… and it doesn’t get laughs… I feel really exposed and like I’ve overshared with some strangers. Then I’d have a gig where the personal stuff would do really well, and it’d feel amazing.”

Audiences are clearly both registering this and relating to it. The laughs and existential moans I mentioned earlier are now stretched out over an entire show of personal resonance with a story of pain and healing, played out by a performer who is hyper-aware of how the audience is perceiving his story as he goes along, and will speak to that reaction when he feels like it.

What interests me here is Acaster’s control of the room. He’s as in control as any old-school comic would want, but he does this by sacrificing the illusion that he’s in control of anything. We trust him because he’s honest about his abilities—he wrestles this thing back on track if he needs to, but if we meet him halfway in this story, we’ll get more out of it. In Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999, Acaster gets to take advantage of the transparency of the set and actively dismiss the bullish comedians who want to shock you for shock’s sake, and punch down in the name of challenging expectations, though he doesn’t name names (he does, it’s Ricky Gervais).

It comforts me to know that Acaster’s incredible precision as a comedian now gets to go toe-to-toe with the comics who give interviews complaining that all this personal soul-bearing works at the expense of actual laughter. It excites me to think that a comedian of his caliber is taking steps that still scare himself this much. And it pains me to think that you might not be caught up when Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999 finally makes its way to you. Go catch up. In the meantime, don’t worry about James Acaster’s personal life. It all worked out. He’ll let you know at the top of the show just in case. “You gotta let people know that they’re about to laugh at it,” he says, “and it’s fine.”

Graham Techler is a New York-based writer and comedian. You’d be doing him a real solid by following him on Twitter @grahamtechler or on Instagram @obvious_new_yorker. A real solid.