The 70 Best Albums of the 1970s

The ’70s sometimes get a bad rap: Often these years are remembered as the musical era that brought us disco at its absolute gaudiest. But there was far more going on in the decade than polyester, sequins and cocaine; the 1970s saw the rise of the singer/songwriter, the birth of punk rock, reggae’s infiltration of the mainstream and the long, strange trip led by some of psychedelia’s finest.

In fact, it’s a decade so musically diverse, we had quite a time whittling it down to our top albums. When we polled our staff, interns and writers, over 250 albums received votes, but ultimately these 70 emerged as clear favorites.

Note: As with our best albums of the 1960s, we’ve limited each artist to two albums. That means artists like Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Stevie Wonder and David Bowie all had some stellar work bumped from the list—but it also means you’ll have more to get angry about, so have at it.

70. Various Artists, The Harder They Come soundtrack (1973)

70. Various Artists, The Harder They Come soundtrack (1973)

There was a lot more to the early years of reggae than Bob Marley & the Wailers, and the best of the rest is brilliantly summarized on this soundtrack album for one of the best fictional music films ever made. Once they realized they weren’t going to get any Wailers tracks, the filmmakers chose brilliantly. As the charismatic outlaw/singer/star of the movie, Jimmy Cliff sang half the songs, but there’s not a bad cut in the original soundtrack’s dozen. Included are reggae’s best-ever ballad (Cliff’s “Many Rivers To Cross”), best-ever pop hook (the Maytals’ “Sweet and Dandy”) and such one-hit wonders as the Slickers and Scotty. The 2003 “Deluxe Edition” reissue adds a second CD with 18 more songs, as smartly chosen as the first disc. —Geoffrey Himes

69. Blondie, Parallel Lines (1978)

69. Blondie, Parallel Lines (1978)

The wondrous pop, rock and disco songs on Parallel Lines weren’t supposed to be on good albums, much less all on the same one. To imagine it is to put “The Loco-Motion,” “I Wanna Be Your Dog” and “Staying Alive” on a mixtape and pronounce it a band. Whether pilfered directly from the Nerves (the breathless “Hanging on the Telephone” takes no prisoners) or stitched together, nursery rhyme-like from Buddy Holly’s “Everyday” (few melodies jangle so timelessly as “Sunday Girl” ), Debbie Harry and Chris Stein’s shrewd, sexy melodicism on these 12 classics clawed its way into the pantheon from the simple ambition to conquer any radio format they touched. One way or another, they sneered. We’re gonna please ya please ya please ya please ya. —Dan Weiss

68. Nick Drake, Pink Moon (1972)

68. Nick Drake, Pink Moon (1972)

Few albums on this list have aged as well as Nick Drake’s final album from 1972, recorded in a pair of post-midnight sessions with just Drake and producer John Wood. The simplicity of acoustic guitar, subtle piano and whispered vocals could have been recorded four decades later—and indeed Drake has sold many more copies of his albums since his death in 1974. And, of course, the heartbreak of which he sings will never become irrelevant. Beauty and melancholy have seldom meshed so completely as on songs that tackle longing, despair and the slimmest rays of hope. —Josh Jackson

67. Devo, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! (1978)

67. Devo, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! (1978)

I think I was 16 when I realized Devo wasn’t a jokey one-hit wonder but one of the greatest rock bands of all time. Not that “Whip It” isn’t an amazing song, but it was a little too goofy and ubiquitous for me to take seriously at that very serious age. If I had heard the spastic art rock of Are We Not Men? first I never would’ve doubted them. It’s not their best album, but it’s the best at convincing serious young rock nerds that Devo were more than a silly footnote. —Garrett Martin

66. Derek and the Dominos, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs (1970)

66. Derek and the Dominos, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs (1970)

For a band that only released one studio album, Eric Clapton, Duane Allman, Bobby Whitlock, Carl Radle and Jim Gordon sure made it count. The supergroup recorded both modernized interpretations of classic songs like “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” and “It’s Too Late,” as well as original compositions like “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?” and the eponymous “Layla.” Though originally snubbed, Layla has continued to be recognized as an explosion of blues-infused rock ’n’ roll and a seminal work in Clapton’s career. —Hilary Saunders

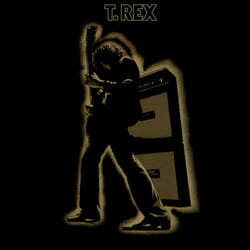

65. T. Rex, Electric Warrior (1971)

65. T. Rex, Electric Warrior (1971)

T.Rex’s sixth record would be worth talking about even if it was a collection of bad Monkees covers, based solely on the sheer awesomeness of its cover art. If that doesn’t make you want to play the electric guitar, there is something wrong with you. Fortunately, Marc Bolan brought the tunes to back it up. “Bang A Gong” and “Jeepster” are the hits, and great ones at that, but spaced-out acoustic numbers like “Cosmic Dancer” and “Planet Queen” and the fuzzy blues riffs of “Lean Woman Blues” give the album its depth and diversity. Add in lyrics about flying saucers, girls and cars, and glam rock has never sounded so weird and wonderful. —Charlie Duerr

64. The Stooges, Fun House (1970)

64. The Stooges, Fun House (1970)

Although The Stooges made their first sonic statement with 1969’s self-titled effort, they didn’t do it right until their sophomore album with the rowdy, Don Galluci-produced Fun House. With the band recording in a raw, live setting, they were almost able to capture their untamable live energy onto tape. The Stooges might have reached a much wider audience with Funhouse’s follow-up, Raw Power, but they never again were able to produce the gritty, warts-and-all intensity seen in staples like “Down on the Street” and “T.V. Eye.” And, maybe to tie in with the album’s title, closing track “L.A. Blues” sounds like Iggy and the boys crying out for help on the way to the loony bin—only this time, they’re using wailing guitars; harsh, stick-splintering drums; and Pop’s unmistakable wail. —Tyler Kane

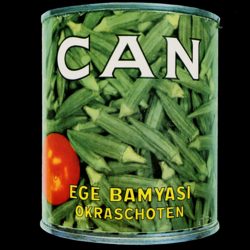

63. Can, Ege Bamyasi (1972)

63. Can, Ege Bamyasi (1972)

Drawing influences from Stockhausen to The Beatles, Can refined their wide range of influences on Tago Mago’s follow-up. The term “krautrock” never fully represented the Cologne collective’s musical breadth, but nevertheless Ege Bamyasi has become one of the sub-genre’s essential recordings. The seven-song record is tense and concise, requiring patience and understanding to fully embrace the group’s experimentalism. But once the allure of tracks like “One More Night,” “Vitamin C” and “Spoon” creeps in, there’s no turning back. —Max Blau

62. Led Zeppelin, Physical Graffiti (1975)

62. Led Zeppelin, Physical Graffiti (1975)

After starting off their career with five studio albums (I, II, III, IV and Houses of the Holy) that ensured their legacy as one of the decade’s definitive rock acts, Led Zeppelin had no need to prove themselves further. That didn’t stop them from putting out their most ambitious record—a sprawling, 80+ minute double album that encapsulates their earlier blues rock and latter mystical psych-synth sound. On the first half of Physical Graffiti, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones and John Bonham crafted some of their most influential songs, including “In My Time of Dying,” “Houses of the Holy” and “Kashmir.” It’s the record’s latter part, however, that brings it all together with a deep-cutting run featuring the band’s most unheralded songs. —Max Blau

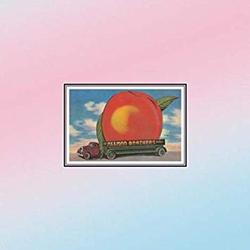

61. The Allman Brothers, Eat A Peach (1972)

61. The Allman Brothers, Eat A Peach (1972)

The first Allman Brothers Band album released after Duane Allman’s death is a sprawling beast that highlights every one of the band’s strengths. Chief among those are Duane’s mastery of the slide guitar and Gregg Allman’s incomparable voice, but Eat A Peach also underscores the band’s multifaceted songwriting proficiency, from the half-hour “Mountain Jam” to the plaintive pop of “Melissa” to the upbeat guitar calisthenics of Dickey Betts’ “Blue Sky. ”—Garrett Martin

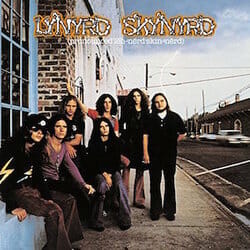

60. Lynyrd Skynyrd, (Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd) (1973)

60. Lynyrd Skynyrd, (Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd) (1973)

(Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd) introduced the world to both the quintessential Southern rock band at the height of its powers and the epic “Free Bird,” empowering decades of slow-witted would-be hecklers with the ability to provoke audible groans from any audience throughout the world. More importantly the album features two of the absolute greatest rock songs of all time, “Simple Man” and the elegiac “Tuesday’s Gone. ”—Garrett Martin

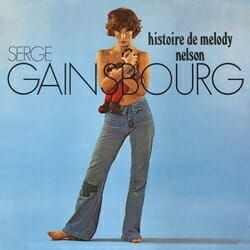

59. Serge Gainsbourg, Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971)

59. Serge Gainsbourg, Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971)

It takes less than half an hour for the French maestro to take us through a semi-autobiographical concise exploration of seduction. Serge Gainsbourg was always known for his varied musical styling from album to album, or sometimes even song to song. However, Histoire de Melody Nelson’s consistency gives the album the sense that it is one long musical piece with different scenes. The term “concept album” is thrown about quite often, but Gainsbourg was more interested in telling a story than creating a perception. The musician’s funky bass lines, orchestral strings and a slam-poetry vocal delivery helps paint the harrowing story of Gainsbourg crashing his Rolls Royce into a teenaged beauty on her bicycle and the ensuing affair, creating a sense that the entire ensemble of songs is taken from a modern performance meant to be performed in opera houses instead of a studio. Only Serge Gainsbourg and his real-life muse Jane Birkin could have allowed the world into such intimate emotions. —Adam Vitcavage

58. The Modern Lovers, The Modern Lovers (1976)

58. The Modern Lovers, The Modern Lovers (1976)

If there was a Socratic ideal form of how we (mis)remember the ‘70s, it’d probably look a lot like The Modern Lovers. Bright, airbrushed guitars, lovably sloppy vocals and an aw-shucks inebriated charm—their 1976 self-titled debut still sounds like accidental genius. It’s difficult conceding that the Lovers were barely more than a myth when it finally hit shelves. Jonathan Richman has gone through many guises and many adorers in his life, but his lasting legacy will forever be centered on those first, gleefully wry sessions. —Luke Winkie

57. Joni Mitchell, Hejira (1976)

57. Joni Mitchell, Hejira (1976)

In 1976, after spending years in the limelight, singing and playing hippie-friendly anthems like “Big Yellow Taxi” and “The Circle Game” for people who came of age in the ‘60s, Joni Mitchell needed time off to reflect and reassess. Her solution was to drive across America by herself, and the time away gave birth to the songs on Hejira, a word that loosely translates as “traveler” in Arabic. Songs like “Amelia,” “Coyote” and especially “Song for Sharon” expressed a new depth and maturity in her lyrics that perfectly fused with the challenging new music she was composing. Supported by a stellar who’s who of modern jazz musicians including Jaco Pastorious, Tom Scott and Larry Carlton, Mitchell’s guitar playing that had previously comprised of little more than folk strumming attained a mastery of expressing, phrasing and tone that has lost none of its power or innovation with the passage of time. Rhythmically complex, daring and beautiful, Hejira’s travelogues of despair and illumination have inspired many to consider it the finest album in her discography. —Doug Heselgrave

56. Gang of Four, Entertainment! (1979)

56. Gang of Four, Entertainment! (1979)

On Gang of Four’s debut, their post-punk mixed with funk is a clear inspiration for bands ranging from Red Hot Chili Peppers to Maximo Park, yet the album’s Entertainment! moniker is quite sarcastic. The album discusses issues like Marxism, Irish prisoners and guerilla warriors, mixed with songs about love and lust. With tracks like “Natural’s Not In It” and “Damaged Goods,” Gang of Four makes dancing to heavy issues not unusual, but rather encouraged. —Ross Bonaime

55. Harry Nilsson, Nilsson Schmilsson (1971)

55. Harry Nilsson, Nilsson Schmilsson (1971)

At a 1968 press conference announcing the formation of Apple Corps., The Beatles were asked about their favorite American artist and group. The Fab Four answered “Nilsson” to both questions. Harry Nilsson may have been a one-man operation, but it’s easy to mistake his perfectly harmonized, multi-tracked vocals for a whole group of talented singers. By 1970, Nilsson had already recorded what would become his most famous songs (“One” and “Everybody’s Talkin’”), but his best album would come a year later with Nilsson Schmilsson. On “Early in the Morning,” the singer shows off his skills as a true melodist, while “Jump into the Fire” is a blistering rock ‘n’ roll tune. Nilsson’s cover of Badfinger’s ballad “Without You” serves as the most heartbreakingly beautiful moment on the record for which he took home the Grammy for Best Male Pop Vocal. But count on Nilsson to provide a lighthearted counterpoint to melancholy with one of the record’s most memorable moments, “Coconut. ”—Wyndham Wyeth

54. Simon & Garfunkel, Bridge Over Troubled Water (1970)

54. Simon & Garfunkel, Bridge Over Troubled Water (1970)

With the release of their glorious swan song, Bridge Over Troubled Water, Simon & Garfunkel began the 1970s with a devastating finale. And what a way to go out: Though they’d already laid the groundwork on 1968’s subtly expansive Bookends, Simon & Garfunkel’s last—and best—album is also their most eclectic. Opening with the gospel-tinged title track, which featured Garfunkel’s all-time finest lead vocal, Bridge Over Troubled Water never relents its focus, even as it sprawls: “El Condor Pasa (If I Could)” is a mystical folk gem; the ramshackle pop of “Cecilia” is the very definition of a sing-along; meanwhile, the aching, psychedelic ballad “The Only Living Boy in New York” is simply the greatest song they ever released—sort of like having your heart demolished and swiftly re-assembled in just under four minutes. —Ryan Reed

53. Joy Division, Unknown Pleasures (1979)

53. Joy Division, Unknown Pleasures (1979)

There might not have been a better band to usher in the ‘80s than Joy Division, a forward-thinking group of English rockers whose sum was more than its individual parts. Vocalist Ian Curtis had an unmistakable, dry vocal delivery that blended perfectly with Bernard Sumner’s atmospheric, yet always distorted and punchy guitar parts. Peter Hook still inspires slews of pick-wielding, gnarled bass parts, and Stephen Morris brought a dancier take on gloom-rock rhythm. It’s hard to think of another debut in the decade that took as many chances and was as self-assured as Unknown Pleasures. —Tyler Kane

52. Big Star, Third/Sister Lovers (1978)

52. Big Star, Third/Sister Lovers (1978)

When it was recorded Memphis’ Ardent Studios in 1974, Big Star’s third album couldn’t generate enough interest from record labels to get a proper release. It took UK fans’ and critics’ enthusiastic response to the rerelease of the first two records in 1978 for the music to ever see the light of day. But the sprawling power-pop masterpiece would have quite an effect on young musicians like R.E.M.’s Peter Buck and The Replacements’ Paul Westerberg. Over one album, Alex Chilton’s lyrics span the range of human emotion, but both the highs and lows are accompanied by perfect pop hooks. —Josh Jackson

51. Talking Heads, Fear of Music (1979)

51. Talking Heads, Fear of Music (1979)

Fear of Music was leaning out of the ‘70s, dropping in August of 1979, and that epochal advantage can certainly earn a lot of asterisks. But David Byrne’s premier pop moment in the Talking Heads canon still feels remarkably singular. The pure exotic pleasures of “Paper” and “Cities” brushed right up against the sardonic “Life During Wartime,” but it all feels remarkably kindled, free of that overshadowing density of their most “important” work. We used to call it New Wave, but now it’s just a lovely template. —Luke Winkie

50. Marvin Gaye, Let’s Get it On (1973)

50. Marvin Gaye, Let’s Get it On (1973)

Aside from earning its spot as the timeless soundtrack for making out (and more), Let’s Get It On symbolized a provocative, profound evolution for Marvin Gaye. More commercialized than his previous themed album, What’s Going On, Gaye’s 12th studio album took to Motown, soul, R&B, funk and the blues to understand the disparities and connections between sex and love. Songs like the heartbreaking, falsetto-laden “If I Should Die Tonight” balance the titular track, resulting in a complex record of human nature and emotion. —Hilary Saunders

49. The Allman Brothers Band, At Fillmore East (1971)

49. The Allman Brothers Band, At Fillmore East (1971)

One year for my birthday, one of my best friends bought me two very different live albums. One was Ben Folds Live! and the other was At Fillmore East. Up until then, I had never really been a fan of live recordings. I mistakenly thought that all live songs should sound just like their studio-recorded counterparts. I also hadn’t been to many concerts at that point in my life, so I didn’t understand there is a certain energy that is trying to be captured with live albums. But I was willing to give At Fillmore East a try at the recommendation of my friend, especially because I had recently gained interest in blues music, and I was relatively unfamiliar with The Allman Brothers. My mind was blown. I couldn’t even begin to comprehend Duane Allman’s gut-wrenching slide-guitar work, and songs like the near 20-minute jams “You Don’t Love Me” and the album closer, “Whipping Post,” begged for repeated listens, despite their length. This can be heard near the end of the former track when the band slows down, gliding into the “Joy to the World” section, and someone in the audience emphatically yells out, “Play all night!” At Fillmore East captures the talent of a band in its heyday that not only played well, but played well together, showcasing the group’s vigor, exquisite timing and precision in what may be the greatest live album of all time. —Wyndham Wyeth

48. Bob Dylan and The Band, The Basement Tapes (1975)

48. Bob Dylan and The Band, The Basement Tapes (1975)

After Dylan’s infamous motorcycle accident in 1967, the singer went into seclusion in the Woodstock area of New York. The members of his recent touring band, The Hawks (later to become better known as The Band), joined him shortly thereafter, and the group of musicians began writing and recording the music that would eventually become The Basement Tapes. Bob Dylan & The Band recorded over 100 tracks during this time, and while most of them circulated for years on bootleg recordings, it wasn’t until 1975 that they were officially released. The album is notable for its sound, which was a distinct turn away from the type of songwriting Dylan had been exploring on Blonde on Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited. The music on The Basement Tapes is characterized by its roots or Americana feel—a stark contrast to the trends of rock music at the time. When everyone else was infusing rock music with psychedelia or using every nook and cranny of the recording studio to create complex production work, Dylan & The Band sent the music world for a loop by going down into the basement and embracing traditional American stylings. You can always count on Dylan to do the exact opposite of what is expected of him. —Wyndham Wyeth

47. Kraftwerk, Trans-Europe Express (1977)

47. Kraftwerk, Trans-Europe Express (1977)

Trans-Europe Express is the most consistent album by one of the most important bands of all time. Kraftwerk found the perfect muse for their minimal electronic pop with this concept album about an old European railway system. The album’s influence reached beyond electronic music or traditional pop, and somehow this cold, mechanical, Gemanic art helped birth hip-hop, with the title track memorably incorporated into Afrika Bambaataa’s seminal “Planet Rock.” —Garrett Martin

46. Crosby Stills Nash & Young, Déjà Vu (1970)

46. Crosby Stills Nash & Young, Déjà Vu (1970)

With the follow-up to Crosby, Stills & Nash’s critically acclaimed debut, the group decided to enlist the talents of Canadian singer/songwriter Neil Young. All of the group’s members, including Young, had already established themselves as musical powerhouses through their work with previous bands Buffalo Springfield (Stills and Young), The Byrds (Crosby), and The Hollies (Nash), and all were on the verge of launching successful solo careers as well. With the addition of Young, CSN gained an extra voice to add to their already complex tidal waves of harmony as well as another unique songwriter. The result turned the band that is often cited as one of the first supergroups into something even better. Despite the tensions within the band that stunted their potential over the following years, the fusion of country/folk songwriting with psychedelic/hippie flair and pop sensibility caused Déjà Vu to become a standout record of its time and the diamond of the group’s catalog. —Wyndham Wyeth

45. The Rolling Stones, Some Girls (1978)

45. The Rolling Stones, Some Girls (1978)

The Stones’ decision to make a New York City record in the late 1970s should have gone drastically wrong. Instead, the veteran rock stars, who most thought were on the final legs of their victory lap (one they appear to still be on), turned in a glorious mishmash of punk, disco, blues and country that silenced their detractors and woke up former fans. From the groove-heavy “Miss You” to the campy country of “Far Away Eyes” and Keith’s rollicking “Before They Make Me Run,” Some Girls is a dirty, sexy mess, much like the city that was its muse. —Charlie Duerr

44. The Velvet Underground, Loaded (1970)

44. The Velvet Underground, Loaded (1970)

Loaded was the final album recorded with Lou Reed, and the band’s clearest attempt at making radio-friendly music. In the time after it came out, Reed distanced himself from the final product, but the trifecta of “Who Loves the Sun,” “Sweet Jane” and “Rock & Roll” is among the best three-song openings on any rock and roll record. It’s as good a soundtrack for the first few minutes of a summer day as there is, and guaranteed by doctors to erase a hangover instantly.*

*Maybe. —Jeff Gonick

43. Tom Waits, Small Change (1976)

43. Tom Waits, Small Change (1976)

Tom Waits’ third studio album, Small Change, had everybody wondering, “Does Tom Waits need a hug?” Waits had become a little too comfortable with life on the road and admitted later on that he had been drinking too much. The jazz influence present in his previous albums did not waiver with this album, but the lyrics became much more dark and depressing. “The Piano Has Been Drinking (Not Me)” is a disheartening, speech-slurred bar tune describing what seems to be wrong with the world but blaming it all on everything that isn’t the cause of the problem. Nothing seems to be going right for Waits in this album. If Waits’ first albums were the upbeat side of jazz, Small Change proved that he understood that it can also express heartbreak and pain. —Clint Alwahab

42. Elton John, Madman Across the Water (1971)

42. Elton John, Madman Across the Water (1971)

A year after Madman Across The Water was released, Elton John made Honky Château, which is considered one of his greatest works, has a stronger foothold in the canon, was better loved by critics and is ultimately probably the better album. “Honky Cat,” “I Think I’m Going To Kill Myself” and “Rocket Man” are classics, indeed, but there’s something special about Madman. It’s a wonderful display of the partnership between Elton John and songwriter Bernie Taupin—Taupin’s ability to tell a compelling story and John using his keys, his voice and his presence to make you care about the characters. There’s the weirdness and sadness of “Levon”—a song full of quirky names and scenarios but a feeling of longing and familial dysfunction all too common, backed with that punch of a chorus. There’s “Tiny Dancer,” which was and will always be great regardless of what sentimental movie scenes soundtrack it, and the powerhouse title track, of course. And even the deep cuts have their moments, most notably the mournful, mandolin-tinged “Holiday Inn.” —Lindsay Eanet

41. The Band, The Last Waltz (1978)

41. The Band, The Last Waltz (1978)

A historic event, such as The Band’s “farewell” concert at Bill Graham’s Winterland Ballroom on Thanksgiving Day, 1976, filmed for posterity by Martin Scorsese, can either inspire musicians to greater-than-normal heights or distract them into bombastic overplaying. The Band rose to the occasion on this album as their best-known songs were bolstered by adrenaline, by Allen Toussaint’s horn arrangements and by the presence of so many friends and heroes. Bob Dylan, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison, Emmylou Harris, Dr. John. Neil Young, Eric Clapton and the Staples Singers all sang with the headliners, each benefiting from as good a backing band as they’d ever had. The album even included a studio session: three new songs, “The Weight” and two instrumentals combined into “The Last Waltz Suite.” An expanded version was released in 2002. —Geoffrey Himes

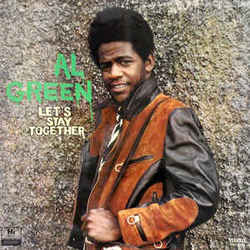

40. Al Green, Let’s Stay Together (1972)

40. Al Green, Let’s Stay Together (1972)

When Al Green released Let’s Stay Together in 1972, retailers of roses and water beds wore smiles—the album quickly became the soundtrack of lovemaking in America. Green’s astonishing falsetto set him apart in the soul-singer pantheon, with Marvin Gaye his only rival in silky smoothness. President Obama covered “Let’s Stay Together” last January at an Apollo Theater fundraiser, delivering a credibly sweet verse before Green himself performed. How great is Al Green? Back in the day, those capricious Greek gods, wickedly fond of changing mortals into narcissus and spider and other flora and fauna, would have made Green a songbird. He’d be singing outside every bedroom in the world. —Charles McNair

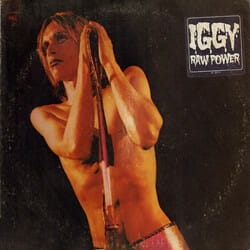

39. Iggy and The Stooges, Raw Power (1973)

39. Iggy and The Stooges, Raw Power (1973)

Raw Power opener “Search and Destroy” is about as iconic as proto-punk gods Iggy Pop and his Stooges got in the ‘70s. The track, with its sloppy, clipping production ushered in a new era for the band, which featured a new name (Iggy and the Stooges instead of just “The Stooges”) help from David Bowie on mixing, and new guitarist James Williamson. The album—which at this point was the band’s most commercially successful by leaps and bounds—featured not only the decade-defining “Search and Destroy,” but other unforgettable, biting tracks like “Your Pretty Face is Going to Hell” and “Gimme Danger.” —Tyler Kane

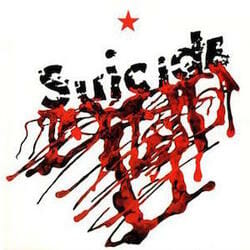

38. Suicide, Suicide (1977)

38. Suicide, Suicide (1977)

Suicide’s eponymous 1977 debut, in terms of style and influence, is one of the most groundbreaking releases in the history of music. I don’t think that’s hyperbole, when you consider that it’s regarded as the first synth-pop record, and has since gone to inspire legions of bands, from Joy Division to MGMT. What’s interesting is that, unlike most seminal records, it still sounds ahead of its time today. The reverb, bleakness and atonal drone might have turned off much of the general public, but like all great artists, Suicide’s Alan Vega and Martin Rev had the balls to sound like sex, danger, madness and ultimately possibility. —Drew Fortune

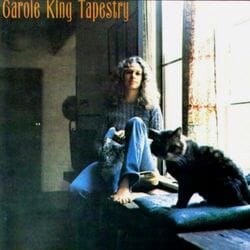

37. Carole King, Tapestry (1971)

37. Carole King, Tapestry (1971)

Tapestry was nothing less than the sound of a generation growing up. I was 13 the first time I heard “It’s Too Late.” It shook me, because it was one of the first pop songs I can remember about love dying, divorce, etc. Sure, there were lots of songs about young love not prevailing —“Breaking Up Is Hard To Do,” that kind of thing. But Carole King sang about adult love not prevailing —about heartbreak and compromise being permanent features of the grownup landscape. Tapestry has always been the ultimate chick album. But more than that, it was a mature album, and the world it described was both as exotic as Tahiti, and as familiar as my parents’ bedroom, down the hall. —Tom Junod

36. John Lennon, Imagine (1971)

36. John Lennon, Imagine (1971)

Perhaps atoning for sins committed in his heavy-handed salvation work on The Beatles’ Let It Be recordings, here co-producer Phil Spector brings a simplicity of instrumentation to Lennon’s brilliantly written tunes. Even today, the album retains its freshness (except maybe for that annoying sax solo on “It’s So Hard”—I don’t care if it is King Curtis). Compared to the soaring production of Simon and Garfunkel’s inspirational Bridge Over Troubled Water a year earlier, the title track relies on the profundity of Lennon’s words with a fitting, uncomplicated arrangement of piano, bass and drums and just a dusting of strings. And then there’s Lennon’s formidable vocals. While he moves us with his sincerity on “Imagine” he tongue-lashes his way through “Gimme Some Truth,” immediately starting with an obvious impatience and disgust at the incompetence of our political leaders. Later, in the same manner, he unabashedly burns his ex-songwriting partner Paul McCartney in “How Do You Sleep?” With every song a gem, this is John Lennon at his multi-layered best. —Tim Basham

35. Elvis Costello & The Attractions, This Year’s Model (1978)

35. Elvis Costello & The Attractions, This Year’s Model (1978)

Elvis Costello had already made a splash with My Aim Is True, but the addition of his own band makes an immediate impact, as the rhythm section of Bruce Thomas and Pete Thomas launch right into “No Action,” colored with organ from Steve Nieve, who’d added so much to “Watching the Detectives.” Songs like “Pump It Up” and “Radio, Radio” are as energetic as anything in his catalog. It’s a rock ’n’ roll record that would make Buddy Holly happy to have Costello wearing those glasses. —Josh Jackson

34. David Bowie, Low (1977)

34. David Bowie, Low (1977)

In 1977, David Bowie had shed his Thin White Duke persona and began cleaning up after the severe cocaine addiction that fueled the Station to Station sessions. He relocated to France and then Berlin to begin work on his next album, Low. The record embraced a highly experimental and avant-garde style that was directly influenced by the work of bands like Kraftwerk and Neu! as well as Bowie’s collaboration with Brian Eno. The result is an LP that is simultaneously compelling and confounding. Polarizing critics and fans when it was released, Low is split into two distinct halves with their own unique sounds. The first is made up less of songs, but rather “song fragments” that seem to start and end from out of nowhere, fascinating the listener nonetheless. The second half is characterized by mostly instrumental sprawling, spacey tracks. Low became the first installment in Bowie’s famous “Berlin Trilogy,” and would go on to become highly influential in its own right through its structure, embrace of electronic sounds, and unique production techniques. —Wyndham Wyeth

33. The Kinks, Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One (1970)

33. The Kinks, Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One (1970)

Some of the best music in existence was written to poke fun at the music industry, which was the source of inspiration for Lola versus Powerman, including tracks like “Top of the Pops,” “Denmark Street” and “Get Back In Line.” The band’s musings on the modern age are still every bit worth pondering and absorbing as they were back then. “This Time Tomorrow” still induces chills; “Lola” can still get crowds of all ages and at all levels of inebriation going. —Lindsay Eanet

32. Michael Jackson, Off the Wall (1979)

32. Michael Jackson, Off the Wall (1979)

Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall marks the icon’s transition from a Motown singer to one of the biggest solo artists of all time, garnering him a Grammy and a quartet of big hits on the Billboard 100. With its single “Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough,” Off the Wall is widely acknowledged as one of the great, enduring pop albums from years past, so it’s easy to forget that the record is also peppered with heartfelt ballads. But the one-two punch of raw emotion (Jackson actually cries at the end of the take for “She’s Out of My Life”) and pop prowess is at the heart of who Jackson really was as an artist, and why his music is still so beloved after so many years. —Rachel Bailey

31. Neil Young, Harvest (1972)

31. Neil Young, Harvest (1972)

While an album’s sales are seldom a reliable measure of its true value, Young’s Harvest struck a chord with record buyers. Billboard ranked it the best selling album of 1972, quite a feat considering the year’s release of now-classic albums by Carole King, Elton John, The Rolling Stones, Stevie Wonder, David Bowie and on and on. Even more amazing, I can overlook radio’s oversaturation of the single “Heart of Gold” and hear it for what it is: a song as pivotal to its time as other classics in theirs, like Hank Williams’ “Your Cheatin’ Heart” or Johnny Cash’s “I Walk the Line.” The album was a further affirmation of a sound Young had already begun with After the Gold Rush. The “unplugged”production of songs like “The Needle And The Damage Done” and “Harvest” mix surprisingly well with the almost Broadway-like “A Man Needs A Maid” and “There’s A World” before closing with a CSN&Y-like “Words (Between the Lines of Age)”. Country-rock before it was “alt.” —Tim Basham

30. Bruce Springsteen, Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978)

30. Bruce Springsteen, Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978)

In 1977, Springsteen’s songwriting made a dramatic shift, breaking with his previous romanticism to write with a hard-edged realism and in a populist vernacular about and for the working-class kids he’d grown up with and still saw in his audience. The result was some of the best songs he’d ever write: “The Promised Land,” “Badlands,” “Racing in the Street” and the title track. The fact that Springsteen insisted that he could “still believe in the promised land” after all the injustices he’d described created the dramatic tension that drove the record. And the songs blossomed from their overly studied studio versions into liberated and liberating live versions, best represented by the bonus DVD of a Houston show on the 2010 box set, The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story. —Geoffrey Himes

29. Patti Smith, Horses (1975)

29. Patti Smith, Horses (1975)

First impressions have always been important in discussions about art, from Elizabethan literature to more contemporary jams. And good Lord, does Horses make an entrance: that dirge of a piano riff, and then Patti Smith, with a slow burn, that line: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins/but not mine.” With the piano and guitar as kindling, the backbeat stoking the flames, that burn builds and builds to the explosion of “Gloria,” the chaotic “ding-dong, ding-dong, ding-dong” of Smith’s heartbeat. And from there, you’re in love, with Gloria, with Patti. Horses is the kind of album people try to talk about and it always turns into a sermon or a sales pitch. When people talk about an artist or an album having “saved their life,” this is the kind of record they mean. It’s the kind of album we wish parents would standard-issue give their children as a means of encouraging personal growth and survival. And as further evidence of Horses’ importance, Smith is still making records decades later, and they’re still great. —Lindsay Eanet

28. Queen, A Day at the Races (1976)

28. Queen, A Day at the Races (1976)

Coming off of the heels of A Night at the Opera (and their biggest hit of all time, “Bohemian Rhapsody”) Queen decided it best to not let the success linger and released A Day at the Races just little over a year later. Like so many of Queen’s albums, this one was an assorted blend of current metal and classical music and meant to be played in the largest arenas in the world. The album weaves through blaring guitars, cathedral pianos, fast and furious vocals and deep ballads, but it’s Freddie Mercury’s gospel-baroque hits of “Somebody to Love” and “Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy” that sent millions of fans over the edge. Once you flip the record and hear the multi-layered vocals and complex melodies, you know the boys in Queen weren’t suffering any slump in the hits department. “Lover Boy” is a short and sweet ragtime moment that doesn’t seem like much, but then turns into another show-stopping sing-along. —Adam Vitcavage

27. George Harrison, All Things Must Pass (1970)

27. George Harrison, All Things Must Pass (1970)

While his mate John Lennon was quick with the catchy hooks for the peace and love movement of the times, it was George who answered with specific instructions, exemplified in songs like “Awaiting On You All”: “You don’t need a love in, you don’t need a bed pan. You don’t need a horoscope or a microscope to see the mess that you’re in.” Co-producer Phil Spector’s wall-of-sound brings a layered depth (listen to “Wah-Wah”) to Harrison’s impressive cache of talent, which included Ringo, Eric Clapton, Badfinger, Dave Mason, Billy Preston and the infamous saxophonist Bobby Keys, whose signature licks were heard on many a 1970s album, like the Stones’ Exile On Main Street. Harrison’s devotion to the Hindu god Krishna permeates the 20+ tracks. The innocently plagiarized “My Sweet Lord” still stands as a symbol of the personal musical exhilaration Harrison must have experienced with his post-Beatles explosion of songwriting, long kept in the shadows by the hugeness that was Lennon and McCartney. —Tim Basham

26. Talking Heads, More Songs About Buildings and Food (1978)

26. Talking Heads, More Songs About Buildings and Food (1978)

More Songs About Buildings and Food launched what would become a career-spanning relationship between Talking Heads’ leading man David Byrne and Brian Eno, whose tight production has been credited with helping the band expand their audience beyond their original stomping grounds at CBGB. The album features some of Byrne’s most delightfully quirky song topics, including songs written from the point of view of art school students (“Artists Only”) and a track about a couple who gets so sick of lousy TV that they simply go out and make their own shows (“Found a Job”). The Talking Heads and, later, David Byrne went on to make a long series of great records, and More Songs About Buildings and Food was their introduction to the wider world. —Rachel Bailey

25. Elton John, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (1973)

25. Elton John, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (1973)

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is perhaps the best example of the magic that was the Elton John-Bernie Taupin songwriting partnership. It produced some of John’s best-known tracks, including the rollicking “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting,” the Marilyn Monroe tribute “Candle in the Wind,” the titular ballad and the karaoke staple “Bennie and the Jets.” John seamlessly shifts from brash to mournful over the course of its 17 tracks, and the result is not unlike when Dorothy steps into the Technicolor land of Oz for the first time. —Bonnie Stiernberg

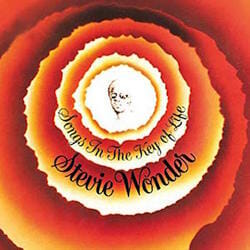

24. Stevie Wonder, Songs in the Key of Life (1976)

24. Stevie Wonder, Songs in the Key of Life (1976)

To celebrate his independence from the Motown machine, Wonder released this album, even more extravagantly packaged than the Beatles’ White Album. He produced and wrote or co-wrote all 21 tracks, handled the lion’s share of instruments and vocals, and released the results as a two-LP, gatefold album with a 24-page booklet and seven-inch EP. All this hubris was justified by the terrific music—catchy as hell, impeccably performed and often very funky. There were four top-40 singles, including two #1s (“I Wish” and “Sir Duke”), plus his much-covered standard, “Isn’t She Lovely.” This closed out Wonder’s five-year, five-album run of peak performance, but it closed it out with a bang. —Geoffrey Himes

23. Neil Young, After the Gold Rush (1970)

23. Neil Young, After the Gold Rush (1970)

Along with Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, After the Gold Rush is one of the greatest break-up records ever made regardless of intention. Even though it has nothing to do with the album, which was inspired by a Dean Stockwell-Herb Berman screenplay, I liked to imagine that it was written to capture the feeling too often ignored by movies and music. The truth of loss that comes after the magic, after the bum-rush of serotonin and possibilities, after you realize the holes inside haven’t been plugged, that the overflow of emotion you poured in ran right out. —Jeff Gonick

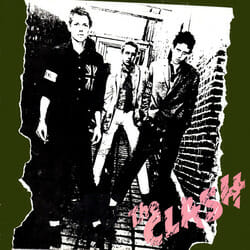

22. The Clash, The Clash (1977)

22. The Clash, The Clash (1977)

At the beginning of the 1970s, John Graham Mellor was, at various points, a gravedigger, a busker in the London Underground, a pinch-hitter vocalist and guitarist for bar bands. Then came the release of The Clash’s eponymous first album in ’77, a year associated forever with the explosion of punk rock. Mellor would become Joe Strummer and lead his band charging onto the scene with their debut, 35 minutes of pure energy, challenging the youth of Britain and the world to listen and to get up and dance (er, pogo). The Clash is an important reminder of how diverse the influences on the scene were, especially for a style of music that seems so simple. “Police & Thieves” recontextualizes the words of reggae greats Junior Murvin and Lee “Scratch” Perry; the harmonica and guitar fuzz on “Garageland” recalls the American R&B and early rock that Joe Strummer played in pubs when he was getting his start. But what stands out are the lean, guitar-driven howlers and sing-a-longs, like gleeful opener “Janie Jones,” “White Riot” and “I’m So Bored With the U.S.A.” Indeed, The Clash took their influences and environment and all the things that were pissing them off and turned it all into a riot of their own. —Lindsay Eanet

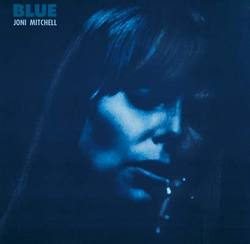

21. Joni Mitchell, Blue (1971)

21. Joni Mitchell, Blue (1971)

It’s no coincidence that the title of Mitchell’s fourth album echoes the title of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, for the singer-songwriter similarly uses modal minimalism and augmented chords to lend a translucent glow to romantic melancholy. Written in the wake of her break-up with longtime lover Graham Nash, these songs have such sturdy melodies and stories that they can afford to be stripped down and stripped bare in the studio, often to nothing more than Mitchell’s soprano and acoustic guitar, dulcimer or piano. The results include her catchiest tune since “Both Sides Now” (“Carey”) and the decade’s best new Christmas song (“The River”). —Geoffrey Himes

20. Elvis Costello, My Aim is True (1978)

20. Elvis Costello, My Aim is True (1978)

Costello’s debut album bridged the gap between the roiling punk energy of the mid-70s and the staid tradition of literate, intimate, popular songwriting that traces from the Gershwins, Berlin and Porter to Buddy Holly and Lennon/McCartney. The record (with the country-tinged ballad, “Alison,” the straight-up rockers “Mystery Dance” and “I’m not Angry,” the politically charged “Less Than Zero”) only hints at the eclectic breadth and scope of Costello’s future catalog, and it sets the musical and fashion stage for the so-called New Wave. Not Costello’s greatest work, but a landmark, highly influential first album. —Mark Baker

19. Pink Floyd, The Wall (1979)

19. Pink Floyd, The Wall (1979)

The legacy of Pink Floyd was not cemented with just The Dark Side of the Moon. The Wall is one of the greatest concept albums of all time. It tells the tale of Pink, a troubled young man raised by an overprotective mother, who is trying to break down the wall in his mind that has been constructed by the authoritative figures in his life. It’s a painful story that most can relate to or at least comprehend, not only because so many have suffered similar pains in life, but because it comes from the story of a real person. Lead singer, bassist and founding member of the band Roger Waters wrote the album based on experiences in his own life. The themes that present themselves throughout the album stitch the story together, making a cohesive 26-track album. The tour that followed the album’s release took it to new heights, turning it into a rock opera. The psychedelic music that Pink Floyd so heavily influenced is present throughout the entire album. Pink Floyd and The Wall not only changed a genre of music, but music itself. —Clint Alwahab

18. Funkadelic, Maggot Brain (1971)

18. Funkadelic, Maggot Brain (1971)

Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain opens with a kaleidoscopic 10-minute suite that ruminates on the pratfalls of drowning in one’s own shit. It only gets weirder from there. Clinton apparently didn’t think much of sampling infant coos on the implacable call to arms “Wars of Armageddon;”“You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks” bedecks a classic 20th Century parable with rolling juke pianos and static flourishes of electronic organ. “Can You Get to That” seesaws on the dueling voices of Gary Snider and Pat Lewis, taking on the air of a violent fantasia. Maggot Brain doesn’t always make sense, either technically or thematically, but it’s big and florid and overwhelming—imagine staring into a gilded, floor-to-ceiling mirror while on DMT. —M.T. Richards

17. Van Morrison, Moondance (1970)

17. Van Morrison, Moondance (1970)

On his third solo release, the Belfast troubadour reached a hallowed space between the irresistible pop structure of “Brown Eyed Girl” and the impenetrable poetry of 1968’s Astral Weeks. Moondance was calculating in its musical precision, but unrestrained in its radiating and joyful imagery, as exemplified in songs like the title track, “Caravan,” and “Crazy Love.” Even decades removed, Moondance still serves as the one-disc, single-artist soundtrack to ‘70s FM radio. —Hilary Saunders

16. Sly & The Family Stone, There’s A Riot Goin’ On (1971)

16. Sly & The Family Stone, There’s A Riot Goin’ On (1971)

With the world crumbling around Sly Stone—including dissolving relationships and political pressure from the Black Panther Party—he and his group nose-dived into the era’s drug culture. During this period, they picked apart their already-successful psych-soul blueprint to make a darker, more somber record. Stone teetered on the edge during the making of There’s a Riot Goin’ On, holding on long enough to create one of the formative post-flower-power psychedelic albums. Within this work, Sly and the Family Stone offer a disillusioned look at the changing landscapes around them, sharing a loosely conceptualized and cynical outlook depicting the signs of the times. —Max Blau

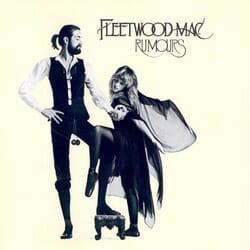

15. Fleetwood Mac, Rumours (1977)

15. Fleetwood Mac, Rumours (1977)

By 1977, hitmaking couple Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks had lost each other in a psychotropic haze. On Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, that haze is thick enough to suck the air out of the room. These 11 tracks saturate in bad faith. “Second Hand News” and “Don’t Stop” put on a happy face, but even they evoke violent sensations: the stinging drip of a cocaine high; the lurking, painful realization that your wedding vows were meaningless. This tension climaxes in “The Chain,” where all five members air out their grievances in a somewhat bizarre dance of kabuki theater. The Nicks-anchored “Dreams” is even darker, employing a theme of inconsolable suffering. From the slo-mo churn of “Oh Daddy” to the boogying disco shuffle of “You Make Loving Fun,” Rumours hasn’t aged a day in 35 years. It might be a snapshot of a band in peril, but it refuses to yellow. —M.T. Richards

14. Stevie Wonder, Innervisions (1973)

14. Stevie Wonder, Innervisions (1973)

By spring 1971, “Little” Stevie Wonder had grown tired of Motown’s upbeat factory sound. The Vietnam War, riots and assassinations put the nation in peril, yet much of Stevie’s music still resembled that sugary soul of the 1960s. Stevie, now an adult, had heavier things to say. By 1973, Stevie’s new direction would reach its pinnacle: Innervisions is arguably his best work, and one of the decade’s definitive albums. It tackled drug usage (“Too High”), inner city blight (“Living For The City”), and religion (“Jesus Children of America”) with refreshing clarity, and solidified Stevie Wonder as a national treasure. —Marcus Moore

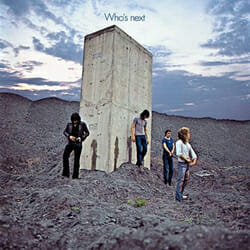

13. The Who, Who’s Next (1971)

13. The Who, Who’s Next (1971)

It’s kinda hard to believe Who’s Next, The Who’s rawest, most powerful and perfect album, came out in 1971. Barely out of the flowery 1960s (and fresh off their psychedelic—and cluttered—rock-opera, Tommy), guitarist-songwriter-vocalist Pete Townshend set to work on Lifehouse, a futuristic follow-up concept album so epic in its proposed scope, it made Tommy’s deaf-dumb-blind-pinball-playing narrative look meager by comparison. While Townshend’s outlandish ideas eventually got away from him, it worked out for the best: Who’s Next, a bastardized version of the original concept album, is hard rock’s definitive masterpiece, crammed top-to-bottom with classics like “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” “Behind Blue Eyes,” “Bargain,” “Baba O’Riley,” and, well, everything else. —Ryan Reed

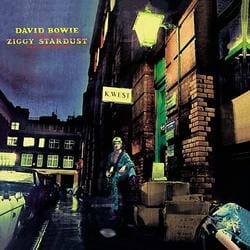

12. David Bowie, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972)

12. David Bowie, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972)

It’s an end of days story, the earth is out of resources. We all are, as my grandmother would say, up shit creek without a paddle. Along comes Ziggy Stardust, an alien returned for our waning days to bring a message of hope. I tend to think bringing giant space-spiders along with you to convince people everything is going to be alright is a questionable decision, but what’s inarguable is the greatness of the album both in terms of concept execution and rock ‘n’ roll range. It’s as timeless as any record of the era, proven by its acoustic recreation for The Life Aquatic, and its historical reinterpretation for The Velvet Goldmine. —Jeff Gonick

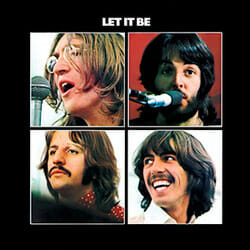

11. The Beatles, Let it Be (1970)

11. The Beatles, Let it Be (1970)

The thing about Let It Be is that it was recorded in the death throes of a band no longer at the top of its game. Many fans don’t realize—because the songs are still, for the most part, all classics—that they were actually playing stylistic catch-up on the album. In Get Back, the large tome detailing the recording of Let It Be, there’s an instance where John tells the other Beatles that they “have to make it sound more like The Band.” The Beatles were no longer groundbreaking or cool when they made Let It Be, but some of their greatest songs came out of the process. The last album they released ended up being a fitting snapshot, a manifestation of every major trope of their music and careers: the sweetness of a McCartney/Lennon love ditty (“Two of Us”), John celebrating Yoko and his ever-present new life (“Dig A Pony”), George Harrison’s growth and presence as a songwriter (“For You Blue”), the Scouse charm and humor that earned them a base in the first place (the Liverpudlian folk song “Maggie Mae”), their ability to pick at our consciousness (“Across the Universe”), their occasional non-sequitur weirdness (“Dig It”), the life-affirming rockers (“Don’t Let Me Down,” “Get Back”). And then, there’s the title track, still ever capable of making the hardest fan weep. “The only currency in this bankrupt world,” we’re told in the gospels of Almost Famous, “Is what we share with someone else when we’re uncool.” If that’s the case, the Beatles made us all exponentially richer. —Lindsay Eanet

10. Sex Pistols, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols (1977)

10. Sex Pistols, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols (1977)

It would’ve been more shocking if the Pistols stuck around long enough to make a second LP. Every marketing gimmick has a shelf-life and the Pistols’ was particularly short. Bollocks is a musical Ouroboros, as its reputation has cycled from “dangerous salvation of rock ‘n’ roll” to “embarrassing cartoon” multiple times over since 1977. If you can ignore big sweeping statements and the misplaced notions of grandeur forced upon it you might be able to appreciate its relatively frills-free take on caustic rock ‘n’ roll recidivism. And hey, at least two people responsible were in on the joke, which is probably two more than The Police. —Garrett Martin

9. Television, Marquee Moon (1977)

9. Television, Marquee Moon (1977)

Television, NYC’s post-punk godfathers, only made two albums during their late ‘70s heyday (including 1978’s oft-overlooked Adventure), but in many ways, they really only needed to release one. 1977’s masterful Marquee Moon was a commercial flop upon its initial release, but its legacy was cemented immediately; capturing the fluid, technical, dynamic unison of the band’s acclaimed live show, Marquee Moon stuck out like a sore thumb from the blooming punk scene: Compared to The Sex Pistols, whose blistering, chaotic debut was released that same year, Television were an anachronism: Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd’s clean, interlocking guitar patterns bordered on the psychedelic, with Verlaine’s snotty, head-cold whine burning blisters over the muscular rhythms of bassist Fred Smith and drummer Billy Ficca. Every moment is devastating, and the winding title track could be the greatest song to ever eclipse 10 minutes. —Ryan Reed

8. The Ramones, Ramones (1976)

8. The Ramones, Ramones (1976)

No single album did more to define the sound and attitude of punk rock. The immortal debut’s 14 songs cover puppy love (“I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend”) and its opposite (“I Don’t Wanna Walk Around With You”); crime narratives (“53rd & 3rd”) and B-movies (“Chain Saw”) against a backdrop of Johnny’s frantic downstroke, Joey’s yelping croon, and the steady backing of bassist Dee Dee and drummer Tommy. More than 35 years after Joey first hollered “Hey! Ho! Let’s Go!” at the album’s opening, da bruddahs’ rally call still resonates. —Bryan C. Reed

7. Miles Davis, Bitches Brew (1970)

7. Miles Davis, Bitches Brew (1970)

After playing at the forefront of jazz for decades, Miles Davis had nothing left to prove by 1970. When Bitches Brew came out that year, it reflected his belief that things had changed and that it was rock musicians and not jazz players who were extending the boundaries of what was possible. With tracks like “Pharaoh’s Dance” and “Spanish Key” averaging around 20 minutes each, Bitches Brew successfully fused Miles Davis’ staccato, wailing trumpet with the psychedelic sounds he’d been soaking up by hanging out in San Francisco and opening up for bands like The Grateful Dead and Santana. More than 40 years after it was first released, Bitches Brew is still one of the most aggressive, confrontational and downright beautiful albums ever recorded. —Doug Heselgrave

6. Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin IV (1971)

6. Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin IV (1971)

It’s difficult to call Led Zeppelin IV the greatest “hard rock” album in music history—only because (in spite of its legacy) it’s much, much more than a “hard rock” album. Led, as always, by the black-magic mojo of guitarist-producer Jimmy Page, Led Zep truly indulged in 1971, branching out into extended progressive-rock (the sweeping, majestic epic “Stairway to Heaven”), medieval folk (the witchy “The Battle of Evermore”) and psychedelic balladry (the emotional centerpiece, “Going to California”), in addition to their trademark electrified blues (“Rock and Roll,” “Black Dog,” “Four Sticks,” “When the Levee Breaks”). Eight tracks, eight classics: It’s one of the greatest rock albums ever recorded, whatever it is. —Ryan Reed

5. Bruce Springsteen, Born to Run (1975)

5. Bruce Springsteen, Born to Run (1975)

After nearly 40 years of consistent veneration from critics and fans alike, there’s little left to say about Born To Run. In just eight tracks, Bruce and the E Street Band constructed a nearly perfect album—dynamic in its instrumentation, euphoric in its lyricism, contradictory in its youthfulness and maturity and iconic in its metaphors and imagery. From the first piano notes in “Thunder Road” through the soul-stirring saxophone solo that closes “Jungleland,” Born To Run captured the collective mindset of a generation and perpetuated it through many more.

—Hilary Saunders

4. Pink Floyd, The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

4. Pink Floyd, The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

What else can be said about The Dark Side of the Moon that hasn’t been said already? It’s one of those records that seems to exist in its own little world. There hasn’t been another quite like it before or since its release, and its impact on nearly every aspect of music—songwriting, production, engineering—is still felt even decades later. In regards to Pink Floyd as a band, the album marked a distinct change of direction in the group’s sound, due in large part to the departure of Syd Barrett, who had been the band’s principal songwriter until his deteriorating mental state forced him to leave the group. Barrett’s mental problems also served as inspiration for much of Dark Side’s concept and themes, which focused on issues like madness, the passage of time, conflict and death. —Wyndham Wyeth

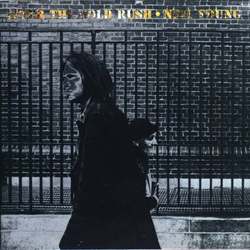

3. The Rolling Stones, Exile On Main St. (1972)

3. The Rolling Stones, Exile On Main St. (1972)

Listening to Exile on Main St. hardly creates a sense of highly-crafted musicianship or fine-tuned production. If you read into the history of the The Rolling Stones’ 12th album, it adds to that notion—Mick Jagger is galavanting throughout the French countryside with his soon-to-be wife while Keith Richards is drugged out on heroin. The band struggled to get all of its members to show up for recording sessions day-in and day-out. Out of this period from 1968-1972 emerged an unpolished realism that ebbs and flows throughout Exile, in which The Stones perfected the art of imperfection, basking in their humanity and all its accompanying honesty. There’s an abundance of triumphant moments within these 18 songs, but the transcendence occurs when the band juxtaposes good and the bad, the flawed and flawless. In doing so, The Stones cap off a golden four-album run, exhibiting the band at the peak of their country-gospel greatness. —Max Blau

2. Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On (1971)

2. Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On (1971)

If Marvin Gaye had been a better athlete—or less obstinate—we might not have gotten one of the greatest albums of all time. In 1970, after the death of his musical partner Tammi Terrell, the Motown singer tried out for the Detroit Lions. When he returned to music, it was on his own terms. What’s Going On was an epic response to his brother Frankie’s letters from Vietnam—politically charged and musically ambitious, a soul album with jazz time signatures and classical instrumentation. The album’s posture was one of lament for the way things were rather than an angry protest, making the message both clear and difficult to tune out. It was such a departure from Gaye’s radio-friendly pop that his brother-in-law Berry Gordy Jr. initially refused to release it on Motown Records. Gaye had produced the album himself with backing from the Funk Brothers, and presented it as a complete nine-song suite. It was a singular vision and one that hasn’t lost its power over time. —Josh Jackson

1. Bob Dylan, Blood on the Tracks (1975)

1. Bob Dylan, Blood on the Tracks (1975)

With good reason, Bob Dylan is most revered for his nearly unparalleled streak of legendary albums in the 1960s (including 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited, and 1966’s Blonde on Blonde), but he saved arguably his finest album ever until 1975, making one of rock ’n’ roll’s most jaw-dropping comebacks with the striking, emotional Blood on the Tracks. Despite being recorded in a ridiculous 10 days (barring a last-minute re-tracking of a few songs), the album remains Dylan’s warmest, richest recording—loads of purring organs, shuffling acoustics, and soulful rhythm sections. But as always with Dylan albums, it’s the words that steal the show, particularly on the bitter epic “Idiot Wind” and the haunting, uplifting “Tangled Up in Blue.” Rock’s most critically acclaimed troubadour kept on releasing wonderful albums after Blood on the Tracks—but he never topped it. —Ryan Reed

GET PASTE RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

The best music, movies, TV, books, comedy and more.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-