The Best Books of 2017 (So Far)

Photo by Frannie Jackson

Editor’s Note: We’ve updated our list to include the best books from January to July. You can view it here.

Now that we’re one-third of the way through the year, we decided to round up our picks for the best books of 2017 (so far). From thrilling sci-fi to Latin American fiction, illuminating memoirs to eclectic short stories, our favorite titles promise enthralling reads for every literary taste.

We’ve assembled 20 books released from January through April, including novels, short story collections and nonfiction books. Browse our favorites below (listed in alphabetical order by title), and check out our lists of the best novels and best nonfiction books of 2016 for more great reading recommendations.

4 3 2 1 by Paul Auster

4 3 2 1 by Paul Auster

4 3 2 1 kicks off with as challenging a premise as Auster has ever constructed: four parallel narratives chronicling four different lives of the same character, Archie Ferguson. Although Auster chooses not to reveal why we’re reading about four versions of the same guy until the last half-dozen of the novel’s nearly 900 pages, 4 3 2 1’s real power radiates from each Archie’s adventures with love, sex, friendship, risks, books, writing and ideas. With this book, Auster has delivered the finest—though, one hopes, far from final—act in one of the mightiest writing careers of the last half-century. —Steve Nathans-Kelly

All the Beloved Ghosts by Alison MacLeod

All the Beloved Ghosts by Alison MacLeod

MacLeod blends memoir and fiction to stunning effect in her short story collection, blurring the lines between life and death as she explores the nature of memory. In “Sylvia Wears Pink in the Underworld” and “Dreaming Diana: Twelve Frames,” she examines our relationship to celebrities after their death. While in stories like “The Thaw” and ‘The Heart of Denis Noble,” MacLeod crafts intimate portraits of individuals at the end of their lives. The collection’s haunting prose is by turns heartbreaking and uplifting, transforming the stories’ heavy themes into something entirely unique. —Bridey Heing

The Animators by Kayla Rae Whitaker

The Animators by Kayla Rae Whitaker

Brimming with electricity, Whitaker’s novel boasts witty prose and two vibrant main characters. Sharon and Mel, a straight laced go-getter and a troubled-genius wild card, are rising stars in the indie-animation scene. Theirs is not so much a relationship story as a portrait of Gen-Y creatives navigating the pressures of success (and their own baggage). And by combining their engaging personalities with a handful of intriguing twists, Whitaker has crafted one of 2017’s first page-turners. —Jeff Milo

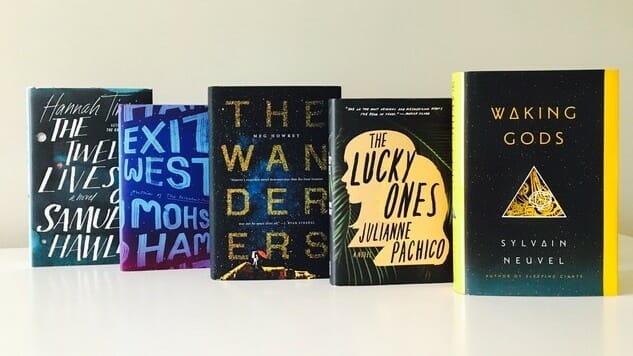

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Hamid has always had a finger on the global pulse, publishing stories hot on the heels of the latest headlines. And though Exit West was completed nearly a year before Trump’s travel ban on Muslim-majority countries, its timing is perfect. The novel opens in an unnamed city (feasibly located in one of said countries) that’s tipping towards civil war and swollen with a sea of refugees. Then we meet Saeed and Nadia, young adults falling in love just as their world is falling apart. Their hope is kindled by rumors of mysterious doorways that transport people to undetermined locations. These doors have supernatural powers, but the way Hamid weaves his story, you’ll believe that they’re real. And, in a way, they are. —Jeff Milo

Flâneuse by Lauren Elkin

Flâneuse by Lauren Elkin

Elkin’s latest book draws on literature, art and history to create a globe-spanning study of women walking alone in cities. The title comes from the French word “flâneur,” a term for privileged men who meander through a metropolis. Women, Elkin argues, have just as much claim to cities as men, but their relationship with cities has long been ignored. From George Sand to Virginia Woolf to Sophie Calle to Martha Gellhorn, Flâneuse demonstrates how women have staked their independence in urban landscapes around the world. By including her own experiences in cities like Paris, London and Tokyo, Elkin crafts an expansive portrait of what it means to be a woman in a city. —Bridey Heing

Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh

Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh

A great deal of (digital) ink has been spilled comparing Moshfegh to Flannery O’Connor, but Moshfegh’s short story collection establishes a firm connection to “horror-adjacent” writers Angela Carter and Shirley Jackson. Like Carter, Moshfegh finds near-infinite literary possibilities in the world of fluids and bodily flaws, from colostomy bags to sagging private parts to foul teeth. And like Jackson, Moshfegh’s characters are often young people on paths toward self-inflicted destruction—or at least continued unhappiness, for happy endings are all but nonexistent here. Moshfegh’s skill lies in her ability to present horrid people without judgment. She isn’t here to moralize, but to deliver enough dark humor that we can almost understand where the nastiness comes from. Almost. —Steve Foxe

How to Murder Your Life by Cat Marnell

How to Murder Your Life by Cat Marnell

Press surrounding Marnell’s book deal was dripping with venom. Yellow headlines blared—even a publication as august as The Atlantic couldn’t resist running the headline, “Cat Marnell’s Book Deal Could Buy a Lot of Drugs.” The entire saga was laced with hatred, because although Marnell was achieving media success directly because of her sickness, she was not afflicted with something relatable like cancer. Her main condition, the least pitied of all pathologies, is addiction. Yet Marnell’s memoir is fucking wonderful. Her voice is her single greatest asset—a pure stylist who can tackle both beauty tips and the savage electricity of a life on amphetamine. How to Murder Your Life turns the addict, trucked with so many gallows watchers’ outrages, into her own fully-formed person. —B. David Zarley

The Kingdom by Emmanuel Carrère

The Kingdom by Emmanuel Carrère

The latest book from France’s master of groundbreaking nonfiction is pure Carrère: forthright, ruthlessly self-analytical and endlessly brilliant. The bestselling author of novels, screenplays, biographies and essays, Carrère begins the book by confronting his past as a devout—if comically pretentious—Catholic, a past the middle-aged writer had apparently forgotten before re-encountering the notebooks he kept from that time. The Kingdom soon transforms into something much weirder, though, as Carrère fictionalizes the early decades of the Church, transforming the book into an extended parable of his own enthralling life. —Lucas Iberico Lozada

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

After decades of brilliant work in the brief yarn vein, Saunders has released his first novel. Set in 1862, Lincoln in the Bardo features the 16th President and a Washington graveyard full of ghosts—including the president’s recently departed son, Willie Lincoln. Saunders’ host of voices provides us with a chance to see what lies on the doorstep of the beyond, and it’s a humdinger; spectral psychology is alternatively denial and dismemberment of the things of this world. By turns moving and hilarious, Lincoln in the Bardo proves there is life after death—and more than short stories in the splendid Saunders. —Jason Rhode

The Lucky Ones by Julianne Pachico

The Lucky Ones by Julianne Pachico

By turns surreal, confounding, terrifying and improbably funny, The Lucky Ones explores Colombia’s specter of guerilla violence through the adventures of a few young women. While the characters’ common history as boarding school students provides a loose framework for the novel’s interlocking stories, The Lucky Ones presents a view of the conflict that is endlessly fascinating, but more prism than lens. Its perpetual perch on the edge of disaster leaves the reader in a state of dread, but Pachico creates a palpable anguish with a light touch, a combination that makes this astounding first novel as irresistible as it is unnerving. —Steve Nathans-Kelly

Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman

Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman

Gaiman has built a decades-long career out of weaving myths into new shapes, perhaps most prominently in American Gods, which borrows from Norse legends. So Norse Mythology reads like a natural culmination of Gaiman’s allusion-heavy path through literature, as the master storyteller joins the ranks of bards who have kept the fragmented pieces of Norse legend alive. Beginning at creation and ending at Ragnarök, Gaiman brings his signature wit and humor to a saga known for its violence and ever-impending doom. His Thor is a lunkhead; his Loki is conniving. And his Norse Mythology is both intrinsically Gaiman and exactly what the title promises. —Steve Foxe

Notes on a Banana by David Leite

Notes on a Banana by David Leite

The James Beard Award-winning food writer’s memoir is about being Portuguese, gay and in love with food. But it is first and foremost about being bipolar. Leite’s work belongs in the great Canon Of Mental Illness, a rending portrait of a bipolar sufferer’s parabolic life—with an extra emphasis on mania, the less understood phase of the disease. It’s Leite’s deft portrayal of mania, written with the celerity and buzzing hagiography that are hallmarks of the condition, that gives Notes On A Banana its chimerical quality: equal parts memoir, case study and, for those who suffer along with Leite, both signal and solace. —B. David Zarley

The Novel of the Century by David Bellos

The Novel of the Century by David Bellos

Not everybody loved Victor Hugo’s masterpiece, Les Misérables, when it was first published in 1862. As Bellos writes in his new book, opinions varied widely: Flaubert and Baudelaire loathed it, but Confederate soldiers christened themselves “Lee’s Miserables.” Bellos shows that Hugo’s giant tome, le Léviathan of French literature, was huge in every way: in its scope (the totality of the 19th century), physical volume (over a thousand pages) and morals—Hugo aimed at nothing less than the salvation of humanity, France and, incidentally, himself. Everything you ever wanted to know about the classic is included; this is the definitive book of the novel of the century. —Jason Rhode

A Separation by Katie Kitamura

A Separation by Katie Kitamura

Kitamura’s new book is a novel-length meditation on what it means to belong to someone else—and then, suddenly, to not. The unnamed narrator has recently separated from her husband of five years, Christopher, but the information isn’t public yet. It’s a private wound that begs to be explored. But when Christopher goes missing in Greece, it’s the narrator who must search for him—despite questioning if she even has the right to find him. Gorgeous, lyrical and provocative, A Separation asks challenging questions about the nature of coming together and breaking apart. —Swapna Krishna

The Stranger in the Woods by Michael Finkel

The Stranger in the Woods by Michael Finkel

The latest book from journalist and author Michael Finkel hangs on one tantalizing question: How was a man able to live in solitude for 27 years in the woods of central Maine? The capture of the so-called North Pond Hermit (during one of the 1,000+ break-ins that sustained him over the years) became major news in 2013, catching Finkel’s attention across the country. The author patiently pursued interviews with the hermit, crafting a fascinating and empathetic portrait of a man who turned his back on the world. —Eric Swedlund

Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enríquez

Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enríquez

Enríquez’s first short story collection to appear in English is part of a wild and weird wave of contemporary Latin American fiction reaching American readers this year. (Enríquez’s translator, Megan McDowell, can claim a significant amount of credit for that happy fact—she’s translated some of the past few years’ most exciting books.) The stories in Things We Lost in the Fire unfold in unexpected ways, tending to descend into horror while remaining very, very funny along the way. Enríquez successfully transforms the banal routines of middle-class life into a terrifying grotesquerie, all while threading a faint whiff of punk rock delivery throughout. —Lucas Iberico Lozada

The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti

The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti

In the nine years since her debut novel, The Good Thief, was published, Tinti has crafted another masterpiece. The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley explores a captivating father-daughter relationship, weaving the pair’s saga through two narrative timelines. The first follows a young girl named Loo as she comes of age in a small Massachusetts town. The second reveals her father’s past through 12 stories chronicling the events that led to his 12 bullet wounds. The result is a fascinating literary thriller, with Tinti building the tension as both timelines count down to the final gunshot. —Frannie Jackson

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle

The second novel from The Mountain Goats’ frontman delivers an unsettling journey to the late-1990s era of video rental stores and dial-up Internet, a recent past that feels strange enough to carry this edgy mystery. In small-town Iowa, a twenty-something video clerk sets out in search of answers after discovering that someone has been splicing homemade footage into the store’s VHS tapes. With Darnielle’s inimitable voice driving a narrative that’s both sad and frightening, Universal Harvester explores loss, grief, resiliency and the never-ending search for human connection. —Eric Swedlund

Waking Gods by Sylvain Neuvel

Waking Gods by Sylvain Neuvel

Countless authors have answered the question, “What if we’re not alone in the universe?” But Neuvel’s response sets him apart. His Themis Files series, launched in 2016 with Sleeping Giants and continued this year with Waking Gods, begins with a deceptively simple premise: a child discovers a giant metallic hand buried in South Dakota. What follows is a global hunt for the artifact’s significance, relayed through interviews conducted by an unnamed man (who quickly becomes a favorite character) and peppered with transcripts, journal entries and other forms of media. Sleeping Giants may have debuted his thrilling saga, but Waking Gods proves that Neuvel’s scope is more daring than readers could have imagined. —Frannie Jackson

The Wanderers by Meg Howrey

The Wanderers by Meg Howrey

What comes before a Mars mission? Why, simulations, of course. In The Wanderers, Howrey tackles the behind-the-scenes drama at Prime Space—a private aerospace company attempting to place astronauts on Mars within four years. Protagonist Helen Kane has just retired after 21 years at NASA, but now Prime Space wants her for a full Mars simulation mission. And once it’s completed, she’ll be the top candidate for the actual journey. Howrey’s literary novel is as much a character study as it is about space, exploring Helen and her crewmates’ profound isolation on their simulated journey. —Swapna Krishna