The 30 Best Books of 2017 (So Far)

Now that we’re over halfway through the year, we decided to update our picks for the best books of 2017 (so far). From thrilling sci-fi to Latin American fiction, illuminating memoirs to eclectic short stories, our favorite titles promise enthralling reads for every literary taste.

We’ve assembled 30 books released from January through July, including novels, short story collections and nonfiction books. Browse our favorites below (listed in alphabetical order by title), and check out our lists of the best novels and best nonfiction books of 2016 for more great reading recommendations.

All the Beloved Ghosts by Alison MacLeod

All the Beloved Ghosts by Alison MacLeod

Alison MacLeod blends memoir and fiction to stunning effect in her short story collection, blurring the lines between life and death as she explores the nature of memory. In “Sylvia Wears Pink in the Underworld” and “Dreaming Diana: Twelve Frames,” she examines our relationship to celebrities after their death. While in stories like “The Thaw” and ‘The Heart of Denis Noble,” MacLeod crafts intimate portraits of individuals at the end of their lives. The collection’s haunting prose is by turns heartbreaking and uplifting, transforming the stories’ heavy themes into something entirely unique. —Bridey Heing

Black Mad Wheel by Josh Malerman

Black Mad Wheel by Josh Malerman

Josh Malerman’s second horror novel amplifies its dread with a surrealist vibe reminiscent of H.P. Lovecraft or Philip K. Dick. Set in the late ‘50s, Black Mad Wheel follows a rock ‘n’ roll band recruited by the U.S. military to investigate an otherworldly sound echoing across the Namib Desert. From there, the novel crescendos with a spate of mysterious disappearances, disturbing Satanic mirages, AWOL ghosts and a thrilling pair of confrontations between two uniquely-represented monstrosities—one in the Namib and one in a U.S. hospital. But Malerman’s greatest feat is setting a tone of brotherly friendship between his main characters, which amplifies the tension when one bandmate (or more?) falls into peril. —Jeff Milo

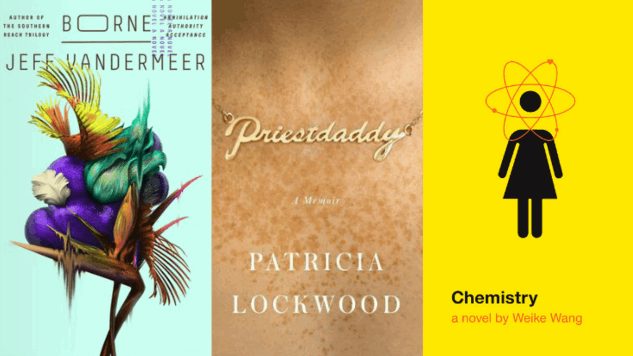

Post-apocalyptic dystopian fiction can be exhausting, especially in today’s political climate. But with Borne, Jeff VanderMeer has created a narrative so refreshing that it defies genre clichés. The novel follows Rachel, a scavenger in a city ruled by malevolent forces and terrorized by a giant flying bear. When she discovers a bizarre creature and chooses to protect it—against her better judgment—she catalyzes events with alarming consequences. The creature, nicknamed Borne, proves both wondrous and chilling, proving that VanderMeer has crafted one of the most compellingly original characters in years. —Frannie Jackson

Chemistry is narrated with such a catching rhythm that you won’t need a science background to fall in love with this contemplative debut novel. Weike Wang’s book boasts a wholly original narrator, whose philosophic musings on sliding through her twenties toward the looming specter of matrimony prove insightful (and always entertaining). The unnamed narrator also faces the stress of graduate school, the pressure of parental expectations and the dense weight of wondering whether her career choice in synthetic organic chemistry was the right move. Wang’s prose draws you in with its wry wit, causing you to wonder what’s in your own makeup that positively (or negatively) charges your more existential thoughts. —Jeff Milo

Francesco Pacifico’s second novel to appear in English, Class, is a humorous, sprawling look at a group of wealthy Roman hipsters who alight on 21st-century New York in hopes of finding some validation for their largely directionless lives. Yet underneath that comic crust is a more complicated tale of forgiveness, restlessness and death. Pacifico’s ability to slyly resuscitate the comedy of manners while deploying a Faulknerian multiple-consciousness narrator—all while thoroughly inhabiting the present moment of conspicuous consumption—has expanded the bounds of contemporary fiction. —Lucas Iberico Lozada

The Destroyers by Christopher Bollen

The Destroyers by Christopher Bollen

Christopher Bollen’s literary thriller is an exemplar of the form—one of those rare novels that not only embraces all the conventions of its genre but elevates them. The Destroyers opens as Ian Bledsoe joins childhood friend Charlie Konstantinou, member of a Cypriot construction dynasty, on the Greek isle of Patmos. When Charlie disappears, Ian is left to piece together his place among the island’s coterie of souls while investigating his friend’s fate. Yachts and reformed actresses aside, by availing itself to the twin tragedies of the refugee and Greek economic crises, The Destroyers rises above the wealthy’s luxe dramas and slots instead into the plights of a cosmopolitan world. —B. David Zarley

The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry

The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry

Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent was one of the most acclaimed books of 2016 in the UK—and it’s easily one of the most engrossing works of historical fiction in recent years. Released in the U.S. this summer, the novel follows Cora Seaborne’s travels to a small Essex village after her husband’s death in 1893. When she arrives, Cora learns about a mysterious beast called the Essex Serpent, which is rumored to be responsible for a recent death and other strange occurrences. Lively and brimming with eclectic characters, Perry’s novel perfectly captures a sense of time, place and peril. —Bridey Heing

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Mohsin Hamid has always had a finger on the global pulse, publishing stories hot on the heels of the latest headlines. And though Exit West was completed nearly a year before Trump announced a travel ban on Muslim-majority countries, its timing is perfect. The novel opens in an unnamed city (feasibly located in one of said countries) that’s tipping towards civil war and swollen with a sea of refugees. Then we meet Saeed and Nadia, young adults falling in love just as their world is falling apart. Their hope is kindled by rumors of mysterious doorways that transport people to undetermined locations. These doors have supernatural powers, but the way Hamid weaves his story, you’ll believe that they’re real. And, in a way, they are. —Jeff Milo

The Golden Legend by Nadeem Aslam

The Golden Legend by Nadeem Aslam

At The Golden Legend’s core is a deep understanding of the centuries-long conflict between Muslims and Christians—and how it continues to be exploited by men in power. Set in Pakistan, Nadeem Aslam’s novel follows several characters whose lives are uprooted when an American man kills innocent Muslims. It’s a narrative that insists on a very simple but terrifying fact: everything is political. God, love, family, justice, faith, power, friendship, secrets—acts of kindness and acts of evil are all informed by politics. And still, The Golden Legend dazzles as much as it devastates. As characters wrestle with the truths of their worlds, Aslam succeeds in reflecting these truths in his prose. And the reader walks away better—and with more understanding—for such an intimacy with such unforgettable characters as these. —Shannon M. Houston

Grown-Up Anger by Daniel Wolff

Grown-Up Anger by Daniel Wolff

New Bob Dylan books appear so frequently these days, and it’s become a rare treat to find one that distinguishes itself by delving into deeper mysteries than the Nobel laureate himself. Daniel Wolff’s provocative new book, Grown-Up Anger, enumerates the ways Dylan fashioned his early public persona around Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl balladeer image, exploring connections in the anger that came across in the two men’s songs. Wolff particularly focuses on the time-transcending rage that made those songs stick, which established Dylan and Guthrie’s voices as connected but distinct, honest, mature, uncompromising and impossible to ignore. As Wolff says, “We could all use a little grown-up anger.” —Steve Nathans-Kelly

Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh

Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh

A great deal of (digital) ink has been spilled comparing Ottessa Moshfegh to Flannery O’Connor, but Moshfegh’s short story collection establishes a firm connection to “horror-adjacent” writers Angela Carter and Shirley Jackson. Like Carter, Moshfegh finds near-infinite literary possibilities in the world of fluids and bodily flaws, from colostomy bags to sagging private parts to foul teeth. And like Jackson, Moshfegh’s characters are often young people on paths toward self-inflicted destruction—or at least continued unhappiness, for happy endings are all but nonexistent here. Moshfegh’s skill lies in her ability to present horrid people without judgment. She isn’t here to moralize, but to deliver enough dark humor that we can almost understand where the nastiness comes from. Almost. —Steve Foxe

How to Murder Your Life by Cat Marnell

How to Murder Your Life by Cat Marnell

Press surrounding Cat Marnell’s book deal was dripping with venom. Yellow headlines blared—even a publication as august as The Atlantic couldn’t resist running the headline, “Cat Marnell’s Book Deal Could Buy a Lot of Drugs.” The entire saga was laced with hatred, because although Marnell was achieving media success directly because of her sickness, she was not afflicted with something relatable like cancer. Her main condition, the least pitied of all pathologies, is addiction. Yet Marnell’s memoir is wonderful. Her voice is her single greatest asset—a pure stylist who can tackle both beauty tips and the savage electricity of a life on amphetamine. How to Murder Your Life turns the addict, trucked with so many gallows watchers’ outrages, into her own fully-formed person. —B. David Zarley

I Was Told to Come Alone by Souad Mekhennet

I Was Told to Come Alone by Souad Mekhennet

As a national security correspondent for the Washington Post, Souad Mekhennet puts herself into situations most people couldn’t imagine. Since 2001, she has provided comprehensive on-the-ground reporting from the frontlines of extremism, interviewing terrorist leaders and their victims to understand what drives them. In I Was Told To Come Alone, she combines memoir with in-depth stories about her reporting to create a complex portrait of identity, conflict and ideology. Mekhennet balances objectivity with understanding, revealing what causes people to accept extremist ideologies—and highlighting the necessity of universal understanding in the face of overwhelming hate. —Bridey Heing

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

After decades of brilliant work in the brief yarn vein, George Saunders has released his first novel. Set in 1862, Lincoln in the Bardo features the 16th President and a Washington graveyard full of ghosts—including the president’s recently departed son, Willie Lincoln. Saunders’ host of voices provides us with a chance to see what lies on the doorstep of the beyond, and it’s a humdinger; spectral psychology is alternatively denial and dismemberment of the things of this world. By turns moving and hilarious, Lincoln in the Bardo proves there is life after death—and more than short stories in the splendid Saunders. —Jason Rhode

The Lucky Ones by Julianne Pachico

The Lucky Ones by Julianne Pachico

By turns surreal, confounding, terrifying and improbably funny, The Lucky Ones explores Colombia’s specter of guerilla violence through a few young women’s adventures. While the characters’ common history as boarding school students provides a loose framework for the novel’s interlocking stories, The Lucky Ones presents a view of the conflict that is endlessly fascinating, but more prism than lens. Its perpetual perch on the edge of disaster leaves the reader in a state of dread, but Julianne Pachico creates a palpable anguish with a light touch, a combination that makes this astounding first novel as irresistible as it is unnerving. —Steve Nathans-Kelly

Notes on a Banana by David Leite

Notes on a Banana by David Leite

The James Beard Award-winning food writer’s memoir is about being Portuguese, gay and in love with food. But it is first and foremost about being bipolar. David Leite’s work belongs in the great Canon Of Mental Illness, a rending portrait of a bipolar sufferer’s parabolic life—with an extra emphasis on mania, the less understood phase of the disease. It’s Leite’s deft portrayal of mania, written with the celerity and buzzing hagiography that are hallmarks of the condition, that gives Notes On A Banana its chimerical quality: equal parts memoir, case study and, for those who suffer along with Leite, both signal and solace. —B. David Zarley

The Novel of the Century by David Bellos

The Novel of the Century by David Bellos

Not everybody loved Victor Hugo’s masterpiece, Les Misérables, when it was first published in 1862. As David Bellos writes in The Novel of the Century, opinions varied widely: Flaubert and Baudelaire loathed it, but Confederate soldiers christened themselves “Lee’s Miserables.” Bellos shows that Hugo’s giant tome, le Léviathan of French literature, was huge in every way: in its scope (the totality of the 19th century), physical volume (over a thousand pages) and morals (Hugo aimed at nothing less than the salvation of humanity, France and, incidentally, himself). Everything you ever wanted to know about the classic is included, making this the definitive book about “the novel of the century.” —Jason Rhode

Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life by Jonathan Gould

Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life by Jonathan Gould

Peter Guralnick’s Sweet Soul Music posited that 1960s Southern Soul brought the races together not only in front of radios and concert stages, but in the studios where integrated bands prefigured post-racial America. The best soul music books since have shredded Guralnick’s thesis, recognizing that the same inequalities that plagued the country framed the lives of Southern soul artists and the musicians who supported them. Jonathan Gould’s Otis Redding doesn’t so much practice revisionist history as simply get a complex story right, capturing the too-short life and career of the immortal Otis Redding with unerring perceptiveness, precision and cultural context. In short, Gould delivers the first biography to do Redding justice. —Steve Nathans-Kelly

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

In her much anticipated second novel, Min Jin Lee traces a Korean family across four generations as they search for home. Pachinko follows its cast across the globe, capturing the zeitgeist of major historical periods like Japanese colonial rule, World War II, the Korean War and the AIDS crisis by demonstrating how global events become personal struggles. Casting history as a backdrop for narratives of resilience and loss, Lee’s novel explores immigrants’ mechanisms of internalized oppression and the fraught position of being a “well-behaved” member of a maligned group. The result is a timely narrative about striving for a better life while being resigned to a second-class status. —Christine An

Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood

Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood

Patricia Lockwood had an unorthodox childhood. As the child of a Catholic priest, she grew up as an anomaly in the faith, but that detail is only the tip of the bizarre Midwestern upbringing Lockwood recounts in her memoir. Her parents are hilarious and strange, her siblings unique and loud, and Lockwood herself is just as mischievous as her Twitter presence would suggest. But Priestdaddy is more than just a series of anecdotes. The book is filthy, moving and complex, with Lockwood not shying away from reflecting on the darker areas of the faith in which she grew up. —Bridey Heing

Quiet Until the Thaw by Alexandra Fuller

Quiet Until the Thaw by Alexandra Fuller

In the same way that Ava DuVernay’s Oscar-nominated film 13th shows that slavery was never abolished (but was merely amended to create mass incarceration), Quiet Until the Thaw shows that genocide against the Native American is an ongoing, white American legacy. Alexandra Fuller relays her characters’ devastating realities, yet she creates a story that is ultimately concerned with the deeply personal experiences of those fighting against an entire nation of powerful men bent on their destruction. Fuller argues in the presentation of her Lakota Oglala Sioux characters that White America has wreaked havoc, but it has not been entirely successful. As long as there are surviving members of these tribes—people passing on stories like the ones she tells here—there exists a legacy that cannot be cut down. Quiet Until the Thaw offers up a distinctive view of America, even as it suggests a new understanding of how great American novels can be written. —Shannon M. Houston

The River of Kings by Taylor Brown

The River of Kings by Taylor Brown

Taylor Brown’s The River of Kings is an almost impossibly vivid novel, rendering Georgia’s Altamaha River and the woods that surround it with spellbinding intensity. Brown’s book recounts two Altamaha River adventures in parallel: the modern-day journey of the fractious Loggins brothers to scatter their hard-ass shrimper father’s ashes, and a fictionalized recasting of the French encounter with Timucuan natives at Fort Caroline in the 1560s. Like Cormac McCarthy and Annie Proulx, Brown possesses rare and wild gifts, writing with an arresting precision and unremitting intensity that can keep a reader’s jaw clenched for books at a time. —Steve Nathans-Kelly

A Separation by Katie Kitamura

A Separation by Katie Kitamura

Katie Kitamura’s new book is a novel-length meditation on what it means to belong to someone else—and then, suddenly, to not. The unnamed narrator has recently separated from her husband of five years, Christopher, but the information isn’t public yet. It’s a private wound that begs to be explored. But when Christopher goes missing in Greece, it’s the narrator who must search for him—despite questioning if she even has the right to find him. Gorgeous, lyrical and provocative, A Separation asks challenging questions about the nature of coming together and breaking apart. —Swapna Krishna

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Taylor Jenkins Reid’s novel is a gripping story following Evelyn Hugo, a legendary Cuban American actress haunted by secrets. And when Evelyn agrees to exclusively reveal her secrets to Monique Grant, a magazine reporter who’s low on the totem pole, everyone is shocked. Why did Evelyn choose Monique? It’s hard to believe that Evelyn is fictional, as she leaps off the page with style, grace and an unbelievable amount of pluck. You’ll pick up Reid’s book expecting to breeze through it, and you’ll be blown away instead. —Swapna Krishna

So Much Things to Say by Roger Steffens

So Much Things to Say by Roger Steffens

In this fine oral history, Bob Marley is considered as a prophet ought to be: from every side. Was he a dyed-in-the-wool original, or a carefully cultivated bridge between true reggae and mainstream pop? Was he a man whose beliefs led to his early death, or the first among the faithful to show the world how to die for a cause? Who does he belong to, save all of us—and if that’s true, what claim can a single time and place have on him? The genius of Roger Steffens’ book is to have everyone else tell the story. Marley’s voice may have sung, “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery,” but the “Redemption Song” can only be sung by a chorus. All of us carry the harmony, and Steffens shows the way. —Jason Rhode

Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enríquez

Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enríquez

Mariana Enríquez’s first short story collection to appear in English is part of a wild and weird wave of contemporary Latin American fiction reaching American readers this year. (Enríquez’s translator, Megan McDowell, can claim a significant amount of credit for that happy fact—she’s translated some of the past few years’ most exciting books.) The stories in Things We Lost in the Fire unfold in unexpected ways, tending to descend into horror while remaining very, very funny along the way. Enríquez successfully transforms the banal routines of middle-class life into a terrifying grotesquerie, all while threading a faint whiff of punk rock delivery throughout. —Lucas Iberico Lozada

The Thirst by Jo Nesbø

The Thirst by Jo Nesbø

Oslo detective Harry Hole will debut on the big screen (in the form of Michael Fassbender) in October’s The Snowman, but the character’s first 2017 appearance is in The Thirst. The 11th Hole novel sets the unconventional, alcoholic, insubordinate and compulsive antihero detective against the most sadistic killer Jo Nesbø has conjured yet. Nesbø is a master of style, balancing action and tension in a plot haunted by a demonic tattoo and ritualistic blood drinking. In Nesbø’s consistently excellent Hole series, The Thirst may well be the pinnacle. —Eric Swedlund

The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti

The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti

In the nine years since her debut novel, The Good Thief, was published, Hannah Tinti has crafted another masterpiece. The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley explores a captivating father-daughter relationship, weaving the pair’s saga through two narrative timelines. The first follows a young girl named Loo as she comes of age in a small Massachusetts town. The second reveals her father’s past through 12 stories chronicling the events that led to his 12 bullet wounds. The result is a fascinating literary thriller, with Tinti building the tension as both timelines count down to the final gunshot. —Frannie Jackson

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle

The second novel from The Mountain Goats’ frontman delivers an unsettling journey to the late-1990s era of video rental stores and dial-up Internet, a recent past that feels strange enough to carry this edgy mystery. In small-town Iowa, a twenty-something video clerk sets out in search of answers after discovering that someone has been splicing homemade footage into the store’s VHS tapes. With John Darnielle’s inimitable voice driving a narrative that’s both sad and frightening, Universal Harvester explores loss, grief, resiliency and the never-ending search for human connection. —Eric Swedlund

Waking Gods by Sylvain Neuvel

Waking Gods by Sylvain Neuvel

Countless authors have answered the question, “What if we’re not alone in the universe?” But Sylvain Neuvel’s response sets him apart. His Themis Files series, launched in 2016 with Sleeping Giants and continued this year with Waking Gods, begins with a deceptively simple premise: a child discovers a giant metallic hand buried in South Dakota. What follows is a global hunt for the artifact’s significance, relayed through interviews conducted by an unnamed man (who quickly becomes a favorite character) and peppered with transcripts, journal entries and other forms of media. Sleeping Giants may have debuted his thrilling saga, but Waking Gods proves that Neuvel’s scope is more daring than readers could have imagined. —Frannie Jackson