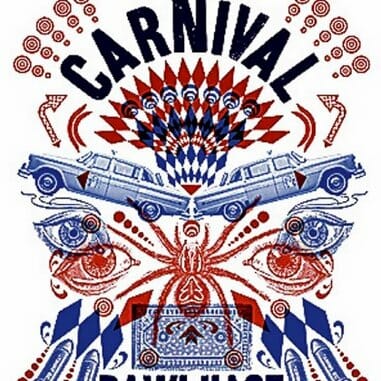

Carnival by Rawi Hage

Welcome to the fun house

With Carnival, his third novel, Montreal-based author Rawi Hage once again takes facts from his own life, blends them with the carnivalesque (quite literally in this case) and pushes things to the border of the fantastic. For those unfamiliar with Hage, he was born in Lebanon, moved to New York in the 1980s, then veered northward to Montreal where he drove a taxi and wrote.

That trek has paid off.

Hage has won the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, along with many Canadian prizes, including the Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction. His writing earned nominations for the Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Award.

Hage’s writing can be poetic, funny and tragic. Most importantly, it always bears the mark of displacement. It makes sense that expats constitute the true heart and soul of this third novel, placed as society’s central players, the people who make the world go round … or at least make people go around in the world. Hage’s characters in this novel drive cabs. Specifically, he writes about immigrant cab drivers who take on larger-than-life, almost mythical qualities.

The narrator, who calls himself Fly, lays the world out for the reader in extreme and contradicting proportions that feel heartbreaking. Fly, in fact, made me fall in love with books all over again. And why not? A book fanatic raised in a traveling circus, Fly is one strand of a web of cabdrivers in a city that loosely resembles Montreal. He separates cab drivers as “spiders” and “flies.” Spiders wait around for prey to find them. Flies wander and roam the city. By name alone, you know where Fly lands.

At one time or other, each of us has very likely met a Fly—the immigrant prophetic taxi driver with a fascinating, mysterious back story. Hage parts the curtain for us, turning taxi driver into universal narrator. And Fly finds much to narrate. Often socially invisible, the driver serves as a witness bordering on voyeur. Coming from a life in the circus where he guessed people’s weight, he now bridges old and new worlds, as well as fantasy and reality between mythologized past and difficult present.

Hage wants the taxi driver in our constructed present, where circuses are a thing of the past and revolutions a path to misled violence, to stand in for priest, witness and confessor. When Fly’s client brings him into an S&M party, the driver watches as “a chained middle-aged man with a hairy back was stomped on by a topless lady in tight pants and a face mask.” Fly thinks of Dante’s Inferno. This self-mythologized man from the circus walks us through a world where his strange kind died and disappeared, yet where dominatrix and leather-clad men chained like dogs replace trapeze artists and contortionists. The world has lost its magic. Yet without ever being naïve or idealistic, Fly shows it to us through his particular fantastical lens, always finding his inspiration in literature.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-