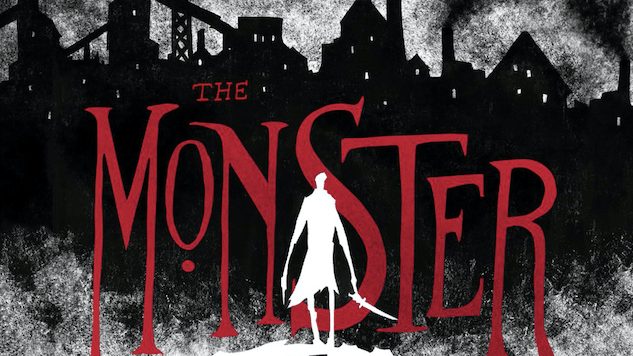

Jennifer Giesbrecht’s Debut Asks, “What If a Magical Oscar Wilde Shacked Up with a Sexy Babadook?”

Tor.com’s publishing list is one of the most visible homes of queer-inclusive science fiction, horror and fantasy on the market today, helping writers like Kai Ashante Wilson, Charlie Jane Anders and Seanan McGuire blaze trails both in LGBTQ+ representation and in cross-genre experimentation. The Monster of Elendhaven, Jennifer Giesbrecht’s debut novella, neatly creeps up alongside the works of those authors. But readers hoping for a nuanced exploration of (monstrous) queer identity to accompany Giesbrecht’s gothic world should lower their expectations.

Elendhaven is a long-past-its-prime city of industry—think Tim Burton’s London from Sweeney Todd—rotting with old magic. Under Giesbrecht’s pen, magic is not a source of wonder but something toxic that spills forth from the Earth; its scant few practitioners use it only for ill and are met in kind. Late in this brief novel, a drunken, diseased character remembers a myth that suggests the end of the world will begin in Elendhaven, and another must correct him: the myth is that the end of the world already has begun in this dying place. And dying is something with which readers will become intimately acquainted, as throats gush blood, plague boils burst and the undying Monster throws himself from greater and greater heights in search of the release that comes when his organs rupture on impact.

If that sounds vaguely sexual, you’re not imagining things: violence stands in for sex from the very first page, where a drunken sailor takes advantage of the monster as a young boy, before the monster claims the name Johann and learns how to stab back at the world. The scant few times Johann and his chosen “master” approach something like intimacy, Giesbrecht pulls the curtains shut before anything can progress past bitten lips and hands pushing against chests. There’s a grand tradition of women and AFAB (assigned female at birth) authors writing horror stories featuring queer male relationships, but The Monster of Elendhaven seems to owe less to Anne Rice or Billy Martin (formerly known as Poppy Z. Brite) than it does to Yaoi, the Japanese manga category for male/male love stories created by and for women.

If that sounds vaguely sexual, you’re not imagining things: violence stands in for sex from the very first page, where a drunken sailor takes advantage of the monster as a young boy, before the monster claims the name Johann and learns how to stab back at the world. The scant few times Johann and his chosen “master” approach something like intimacy, Giesbrecht pulls the curtains shut before anything can progress past bitten lips and hands pushing against chests. There’s a grand tradition of women and AFAB (assigned female at birth) authors writing horror stories featuring queer male relationships, but The Monster of Elendhaven seems to owe less to Anne Rice or Billy Martin (formerly known as Poppy Z. Brite) than it does to Yaoi, the Japanese manga category for male/male love stories created by and for women.

In most yaoi tales, men aren’t represented as complex queer individuals but are used as stand-ins for heterosexual pairings, with one partner clearly defined as the more masculine aggressor and the other as a more feminine object of pursuit, who is expected to resist, resist, resist and, eventually, submit. Johann’s perverse relationship with Florian, a sorcerer whose long-held grudge drives the novel’s plot, follows the yaoi template to a T. Giesbrecht is exacting in her descriptions of Florian as a perfumed dandy covered in greasepaint and dwarfed by extravagant clothes. Johann, by contrast, is described almost entirely by his ability to blend into the shadows. For most of the novel, Florian is the only one who appears to see Johann, which is perhaps The Monster of Elendhaven’s most resonant queer theme: for those who feel invisible, even monstrous, sometimes being seen is enough.

Giesbrecht never quite decides if Johann and Florian are ill-fated lovers or two adrift souls using the other for selfish means, but the necessities of the plot eventually tilt the dynamic toward the latter. Despite jacket copy selling The Monster of Elendhaven as a “tale about murder, a monster, and the sorcerer who loves both,” the sorcerer seems to love murder more single-mindedly than he loves the monster. Perhaps there’s a version of this story told from Florian’s point of view, which dives deeper into the complexities of his relationship with Johann. Instead, Johann is our focal point, and he approaches life with the largely unbothered drive of a shark, always swimming in search of the next warm place to rest his sharp bits.

In the absence of a (com)passionate dark love story or a titillating will-they-won’t-they, the appeal of The Monster of Elendhaven lies in Giesbrecht’s florid prose. It’s delightful to read similes as dramatic as family heirlooms scattered around the city “like bone and blood when a head is blown open by pistol fire.” There are times, though, when Giesbrecht’s cleverness feels gratuitous. When a character simply sits down in a booth, we’re told that she “slid in like a fold of paper,” a line that might feel more at home in a pulpy gumshoe novel.

Complaining about excess in a novel about Magical Oscar Wilde shacking up with Sexy Babadook to commit mass murder is missing the point, though. Giesbrecht has indeed, as the front flap promises, painted a “darkly compelling fantasy of revenge.” But just as Johann continuously searches for a pain exquisite enough to leave a lasting mark, queer readers may find themselves feeling curiously unmoved by The Monster of Eldenhaven’s doomed romance.

Steve Foxe is the author of dozens of comics and children’s books for properties including Pokémon, Transformers, Adventure Time, DC Super Friends, Steven Universe and Grumpy Cat. He was the editor of Paste’s comic section (when it existed) and has contributed to PanelxPanel, The MNT and The Comics Journal. He lives in Queens, where he tweets about comics, Disney theme parks, scary movies, his boyfriend and their dog at @steve_foxe.