New American Haggadah by Jonathan Safran Foer and Nathan Englander

New Haggadah a brave, gorgeous disappointment

Books Reviews Jonathan Safran Foer

The Haggadah is a short book of prayer, narrative, homily and philosophy that Jews read aloud around the dinner table on the first evening or two of the Passover holiday. Passover occurs at the full moon of a lunar month following the spring equinox, and so is a feast of renewal, farming and light. But in religious terms, it commemorates the liberation of Israelite slaves from the land of Egypt by their God, who “with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm” brought them out of their dismal bondage and led them, with a pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night, into the desert. There, they received God’s law, or Torah, and then for 40 years wandered to reach the Promised Land.

The service itself is called a seder, meaning order, and it has long been the single most observed Jewish ritual in the United States, as it was in the Former Soviet Union where Judaism was suppressed. This fact fits with the home-centered nature of Jewish religion, despite the parallel importance of the synagogue. As a tale of both divine aid and human liberation, the Passover story has always been an inspiration to others. It is about 2,500 years old, and as the seder developed over the centuries it took on aspects of Talmudic debate, Greek symposium, Roman feast and Hasidic revelry.

The Last Supper, which many Christians commemorate with communion, was a Passover seder, the wafer a kind of unleavened bread. In another ancient seder, mentioned in current ones, senior rabbis debated finer points of the seder until their students came in and called them for morning prayers. During the Inquisition, some secret Jews got into the habit of holding small Haggadahs on their laps under the table, so that they weren’t obvious to prying eyes at the window; some of their descendants do it to this day. And on a lighter note, President Obama and his family celebrate seders annually in the White House with their Jewish staff.

It’s not much of a stretch for an African-American. Centuries of spirituals have invoked the burden of slavery, the hoped-for intervention of God and a promised land in a home over Jordan. “I’ve been to the mountaintop,” said Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. on the last night of his life, invoking the last days of Moses. “I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know… that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

It’s also not much of a stretch for a president. The rhetoric of the American Revolution was often imbued with the imagery of Exodus. In 1776, Benjamin Franklin proposed that the Great Seal of the United States show Moses lifting his rod over a drowning Egyptian army. Thomas Jefferson proposed the more peaceful image of the Hebrews following God’s pillars of cloud and fire. In 1789, newly elected President George Washington, congratulated by the Jewish community of Savannah, Ga., wrote back in part:

May the same wonder-working Deity, who long since delivered the Hebrews from their Egyptian Oppressors, planted them in the promised land—whose providential agency has lately been conspicuous in establishing these United States … continue to water them with the dews of Heaven and to make the inhabitants of every denomination participate in the temporal and spiritual blessings of that people whose God is Jehovah.

So when Jews sit down to a Seder it’s not an exaggeration to think that they are bemoaning all human oppressions (sometimes explicitly mentioned) and commemorating all liberations.

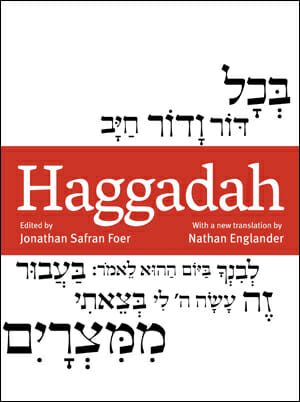

It is always a good thing when a new Haggadah adds to the library of versions we have, even though there are thousands. The newest is edited by novelist Jonathan Safran Foer, designed by Oded Ezer and translated by the gifted fiction writer and playwright Nathan Englander, who was raised as an Orthodox Jew.

As a work of design, this newest Haggadah is gorgeous, a delight to hold and behold. I don’t like the dull black-and-white covers or the bright red-and-white paper stripe, but leaf through the book and you will find page after page of full-color illustrations mostly in the shape of Hebrew words or phrases with an abstract-expressionist flourish. The result is sumptuous but meaningful blotches that ooze across the page. By making the illustrations mostly text-based, Ezer rather brilliantly evokes the illuminated manuscripts of some of the great Haggadahs over the centuries. For a culture steeped in texts from the beginning, this is a particularly apt choice.

The decision to put some commentaries in a column at the tops of the pages, to be read after turning the book 90 degrees, is an interesting one. You can ignore them easily if you like, but when you turn the book you find out fascinating things about seders and Haggadahs of the past, moving chronologically through the centuries. (I learned, for example, that in 1840, after a blood libel episode in Damascus, The Times of London ran a complete translation of the Haggadah to show that it contains not the remotest reference to Christian blood.) The longer interpretive commentaries, by such luminaries as Nathaniel Deutsch, Jeffrey Goldberg, Rebecca Newberger Goldstein and Lemony Snicket feel suitable, and help make accessible the meaning of the core Hebrew and Aramaic texts.

My difficulty, surprisingly, is the translation. Surprising, because I love Nathan Englander’s short stories (especially those in his first collection), and I know he has a great feeling for Jewish tradition despite (like me) having lapsed from it. He has lived in Israel, and I am guessing his Hebrew is much better than mine. I also know that he spent many months studying the Haggadah with a knowledgeable partner, this being the classic way to learn Jewish texts. I’m very glad that he tried this.

My problem lies not with the technicalities of translation, but with the fact that, for this reader, much of it doesn’t scan as English, and I think that is because Englander tries too hard to get away from the phrasing of more traditional versions. There is nothing wrong with this—we certainly need to be jarred out of our complacency, and this is one way to do it. Sometimes it works well, as in this gloss of a key Aramaic passage:

This is the poor man’s bread that our fathers ate in the land of Egypt. All who are bent with hunger, come and eat; all who are in dire straits, come share Passover with us. This year we are here, next year in the land of Israel. This year we are slaves, next year the liberated ones.

But even this has problems. I understand “poor man’s bread” as opposed to the more conventional “bread of affliction.” But most recent Haggadahs have made a brave attempt to de-gender the text in translation. This cannot be done in full, but why not try? I have in front of me what was for a time the official Haggadah of the Reform movement in Judaism, beautifully illustrated by Leonard Baskin; the Feast of Freedom Haggadah of the Conservative movement, also visually appealing. I also hold the recent, more easily available Gates of Freedom Haggadah. All say “that our ancestors ate” instead of the words chosen by Englander. And why the multisyllabic “liberated ones”? Other Haggadahs use some variant of “free.”

The numerous Hebrew blessings afford similar choices. Certainly we don’t want the archaic “Blessed art Thou O Lord our God, King of the Universe… “ that many of us grew up with. But suppose we take one pivotal blessing and see what Englander does with it:

You are blessed, Lord God-of-us, King of the Cosmos, who breathed life, and sustained life, and shepherded us through to the current season.

I like “You are blessed” as a replacement for “Blessed are you” or the common “We praise you,” which though less literal may better capture the spirit of the Hebrew phrase. “God-of-us” did grow on me after many repetitions (as opposed to “our God”), but why the hyphens? They make the phrase a coinage that seems stilted and forced. I like “Cosmos,” but why not “Sovereign” or “Ruler” as many de-gendered translations have it, rather than “King?” It’s more of a mouthful, but it includes Queens.

“Lord” is harder to deal with, but not impossible. The Hebrew is written not as a word at all but as a kind substitute for the Hebrew letter equivalent of Yahweh. It is pronounced “Adonai,” which literally does mean “Lord,” but which is now often carried into English as “Adonai.” Englander does this with other Hebrew words such as matzah (unleavened bread) and hametz (leavened bread and other food forbidden on Passover). And I’m particularly puzzled by “who breathed life, and sustained life” because, just like the word he translates as “shepherded us,” the Hebrew words are personal: “gave us life; sustained us”). Depersonalizing them seems to reduce the blessing’s power.

After the feast, there is more to the service, including a third and fourth cup of wine, a number of songs, and quotations from the Psalms, always treacherous territory for a translator because they have been done so well. Still, Englander succeeds with some of this (p. 101):

Shed your wrath upon the nations that do not recognize You, and on the kingdoms that will not proclaim Your name. For they devoured Jacob, and his dominion they laid bare. Pour upon them Your indignation and let Your rage engulf them. Pursue them in anger and annihilate them from under the heavens of the Lord.

In other places I find myself wishing for a more traditional version. Here’s Englander (p. 82):

He raises up the impoverished from dust,

from rubbish heaps. He lifts the poor,

To seat them with princes,

among the noblemen of His realm,

He restores the barren of the house,

and a mother of children rejoices.

And here is a very slight update of the great King James Version (Psalm 113):

He raises up the poor out of the dust and lifts the needy out of the dunghill,

That he may set him with princes, even with the princes of his realm,

He makes the barren woman keep house, and be a joyful mother of children.

Jonathan Safran Foer, in the April 1 New York Times, touted his new Haggadah with a quite unfair comparison. He mentioned that there have been 7,000 or so versions, but he only compares this one to the little Haggadah given out for free by the millions by the makers of Maxwell House Coffee. That one is comforting to people because it is traditional, convenient, and you can’t beat the price. Nevertheless I agree with Foer that it should be retired and replaced with something vibrant and new. Perhaps a more fair comparison would be to some of the versions I’ve mentioned above.

Graphically, this is a beautiful book and would make a beautiful gift. I will enjoy having it in my library. Practically, I don’t see it at most people’s seder tables. At $30, it’s too expensive for larger groups, and its oversized format will cause many a spilled glass of wine and clash of elbows, especially when it’s turned to read the commentaries. Also, it has no transliterations—a spelling out of key Hebrew prayers and songs in English letters—which will tend to make non-Jews and Jews who can’t read Hebrew feel left out. The absence of any attempt to make the translation more gender-neutral will also not make women and girls feel optimally welcomed.

All that said, my favorite Haggadahs are out of print, and I wish there were more choices. I’ll continue with my old ones, modified with various additions—excerpts from MLK’s “I Have a Dream” speech, for instance, and Yiddish and Judeo-Spanish versions of the Four Questions—and hope for better versions in the future. If you’re looking, there are many good things online, and you can mix and match and add things of your own if you’re not too strict. For a religiously correct touchstone, find a version on an Orthodox Jewish website and work from there. Or, you can always fall back on that old standby from Maxwell House.

The main thing is to celebrate freedom. Whether you think God or people are responsible, there is nothing sweeter than liberation. Slavery takes a different form in every generation, and the Haggadah in every version reminds us to resist, not just for ourselves but on behalf of all who suffer.

Melvin J. Konner holds Ph.D. and M.D. degrees from Harvard University, and is Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor in the Department of Anthropology and the Program in Neuroscience and Behavioral Biology at Emory University. He spent two years among the !Kung San (Bushmen), and has taught at Harvard and then at Emory, for about 40 years. He is author of 10 books, including The Tangled Wing, The Jewish Body, and The Evolution of Childhood. For more by and about him, visit www.jewsandothers.com and www.melvinkonner.com.