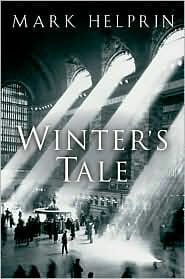

Mark Helprin

I’ve spent 35 years as a reader and literary critic, and still, to this day, I have never found a more stunning, courageous and powerful work of ?ction than Winter’s Tale, Mark Helprin’s millennial New York epic.

On my ?rst read, I stayed up through an entire night, ?nished the whole 768-page novel and wept for a full 15 minutes, then turned back to page one and started again. I personally bought, oh, maybe 50 copies of the book and gave them away to friends, pressing it upon them with the fervor of a mad evangelist. I try to read the book once a year, as a reality check and a spiritual bracer. I made two trips from California to interview Helprin in his New York home, trying my damnedest to understand the mind where this colossal, towering work of the imagination originated.

Until now, though, I’ve never written about Winter’s Tale, out of abject fear. I was unsure that I could do the book justice, as was critic Benjamin DeMott in the New York Times Book Review, who wrote, “I ?nd myself nervous, to a degree I don’t recall in my past as a reviewer, about failing the work, inadequately displaying its brilliance.”

Winter’s Tale spans the latter half of the 19th century and all of the 20th, and probably best ?ts into the very wide con?nes of Magical Realism, although any genre categorization inadequately and unfairly represents its scope and breadth.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-