When Per Petterson emerged on the American literary scene last year with Out Stealing Horses, the critics flipped—both over the novel and the Norwegian author’s story. Petterson survives a handful of close family members who died in a ferryboat fire circa 1990.

Since the tragedy, Petterson has written only one book that closely relates to his terrible experience, In the Wake. As The New Yorker put it, “What happened to the Scandinavian Star seems to have transformed Petterson as a novelist; although there is no mention of the ship’s fire in his other books, it burns on every page.”

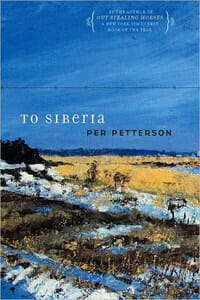

Indie powerhouse publisher Graywolf brought Petterson to the states in 2007 (though he had long been a name in his homeland). Out Stealing Horses did so well here that the FSG imprint followed up with the Oct. 2008 release of To Siberia, a 1996 novel with similar themes and the same elderly-narrator-reflecting-on-her-life plot construct.

Unfortunately, this year’s publication doesn’t have the same appeal as its predecessor. Siberia is a harder novel all around—the prose is less accessible, the timeline staggered and frustrating, and it never quite develops the same narrative hook.

The story centers on a young girl growing up in the reaches of northern Denmark pre-WWII. Her sixty-something self recreates a grim adolescence, through the beginning of the war, her travels and subsequent illegitimate pregnancy. The events and people in her life—a drunk grandfather who commits suicide, a broken, penniless father, a mother whose gratification lies only in religion—though harsh, are leant a scope of bright, naïve frankness. This inclination is inspired, not by the narrator’s youth, but by her brother, whom we discover to be the singular connection of her story.

Jesper is reckless, passionate, a junior socialist at 12—in other words, the counter to the rest of the family. He calls our unnamed narrator “Sistermine,” the only appellation she receives throughout the book.

To Siberia is a novel about distances; both brother and sister are searching for an escape from the unforgiving landscape of their youth, as she yearns to bridge the gap between their futures.

In the first chapter, the two make a blood pact to flee their hometown—he’s got his eye set on Morocco, as she longs for Siberia—and in her vision the tundra of Siberia holds all the warmth of Jesper’s presence. “I shall sit in the train and look out of the window and talk to people, and they will tell me what their lives are like… and then we’ll drink hot tea from the samovar and be quiet together just looking.”

Jesper’s temerity leads him to the early death we’ve predicted, and the bulk of the novel drudges uneventfully without him. Like Out Stealing Horses, Siberia is about nostalgia, but this time around the protagonist is stagnant. We don’t discover anything about her, only what she clings to, or desires in her old age, and that may be the point.

But the focus of her nostalgia is abducted from the text and we’re left with a great deal of melancholy narrative—from the icy characters to the wintry prose. This coldness makes the book difficult to navigate, but forms a background against which the memories of Jesper burn brightly, feverishly. Sistermine never makes it to Siberia, not in body. The memories of her brother replace the dream.