If you ever have the bounty of standing on the rim and looking down into the astounding beauty of the sacred Navajo landscape of Canyon de Chelly, you might possibly have a sudden urge to stay longer than you’d originally planned.

If that happens, you’ll probably want to check in at the tribally owned Thunderbird Lodge nearby. That evening, you could wander over to the cafeteria, housed in the original 1896 trading post, and maybe have some fry bread with honey. When you’re full, try sitting out under the cottonwood trees in the abiding quiet and reading a good book until the high-plateau Arizona light fades in the West.

No book? Well, you can buy one in the Thunderbird’s gift shop. They’re on a rack by the check-in desk not too far from the rug room, where you’ll see piles of beautiful handwoven Navajo rugs. There’s a catch, though—they only have books written by one author.

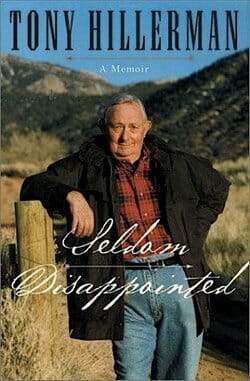

And Hillerman, who made his passage into the Great Beyond three years ago, wasn’t even a Navajo. Yet Navajo schoolchildren all read his books, he was adopted as a Special Friend of the Tribe, an honor bestowed on very few, and the body of his work has personified the Navajo zeitgeist for the rest of world for the past 40 years.

Just for a moment, try to imagine the magnitude of that achievement. No American author, maybe no author anywhere, has ever done this before—become a defining voice for an entire ancient tribal culture not his own.

Anthony Grove Hillerman was a Depression child, born in the Oklahoma Dust Bowl in 1925 and growing up there in the 1930s. Born 50 miles and a little more than a decade away from Woody Guthrie, Tony came up rural and hard-scrabble. “We were poorer than the Joads,” he liked to say. “They had enough money to leave.”

His family farmed cotton and ran a small store in Sacred Heart, Oklahoma, population 34 souls, and Tony’s earliest memories center around the stories he heard there. Seldom Disappointed unfolds with the quiet country cadences of the storytellers that consistently suffuse Hillerman’s prose.

“Blessed are those who expect little,” his mama told him, “they are seldom disappointed.” That’s not just the title, but the deep theme of this powerful memoir—the kind of simple wisdom that informed Hillerman’s entire life, forming the character that attracted him to the selflessness of the Navajos.

When young Tony came of age and was ready to go to school, his father decided, because the one teacher at the public school was rumored to be a member of the Ku Klux Klan, to send his boys to an Indian girl’s school.

The children of the local tribe, the Potawatami, became Tony’s childhood peers and playmates. Much of the early going in Seldom Disappointed brims over with the stories of Hillerman’s rascal childhood among what he affectionately calls the Potts, and his darkly delightful Depression tales describe a time and a place that may be forever extinct—an idyllic, poor but free life without indoor plumbing or outdoor restrictions, where kids with no electronics created their own games and pastimes and fantasy worlds.

The book soon reveals that this sense of unfettered play and creativity contributed mightily to Hillerman’s development as a droll, understated storyteller:

“As grade schoolers, we were also playing Cavalry and Comanches, riding imaginary horses through the woods, creeks, and cow pastures, carrying wooden sabers, horseweed stalks as lances, and using clay balls (carried in old socks hung from the side buttons of our overalls) as ammunition. The rules required one hit by a missile to fall and cheating was rare. Sacred Heart offered a limited recruiting pool for our wars, and the genuine farm boys away from the village were kept busy chopping cotton, plowing, and so forth. Usually we had only Barney and me, Cousin Cecil from down the section line, [and] the three Delonie boys…

“The Delonie boys, being Indians, were assigned Comanche roles. But every Saturday evening the Rex Theater in Konawa would be opened and a movie would be shown. These movies in the 1930s tended to be westerns and the Delonie boys saw one of these. This made them aware that in Cavalry vs. Indian battles the Indians lose. Henceforth, even though as Potawatomi’s they had no aversion to shooting Comanches, we Hillerman boys had to alternate in the roles.”

The boyhood war games inevitably gave way to the brutality of the real thing. Tony went off from rural Oklahoma to World War II as a mortarman in the European Theater. Almost half of Seldom Disappointed deals with that formative part of Hillerman’s life; his maddening, terrifying account of combat in all its randomness, suddenness and stupidity forms the core of the book. Tony tells a harrowing tale, one filled with the black heart of war; the gore in the trenches; the shock of the bullet and the grenade; the terrible dark humor of the grunt and the scorn-inducing, plain pig-headed incompetence of all military intelligence and most military commanders.

The middle section of Seldom Disappointed makes for a magnificent war memoir, because it spares nothing and no one. Hillerman tells the story of the European war with the Germans in a spare, unsentimental way, castigates himself for his own mistakes and missteps, and faults everyone, including himself, for war’s moral failings. He never sanitizes war from the grunt-level view, and he spares us from the recently fashionable greatest-generation-hero tripe-and-treacle. Because he spent much of his postwar life as a journalist, he casts a reporter’s eye for detail and nuance on it all, which makes his memoir a scathing, searing piece of reportage:

“The plan seemed to be to make a stand along the asphalt road and I was signaled to hustle down it. I hustled, my 1902 pistol in my hand. I scrambled up the steep road embankment, flopped on my belly. Just as I did, a German hustled up the other side of the embankment, crouching, carrying a machine pistol. He pointed it at me. I shot him.

“I have relived that moment often. At first, with no particular emotion except relief, remembering him seeing me, jerking his machine pistol toward me, his body slamming backward from the almost point-blank impact of the heavy .45 slug. But soon my imagination gives him a personality. This was face-to-face killing of a man, not the impersonal killing we had done with the mortar, where the victims were an invisible enemy in a machine gun position, or some hypothetical person who might be on the street when you fired the required harassing rounds.

“The German dropped into a crouch on the edge of the single-lane asphalt directly across from me and perhaps fifteen feet away. I seem to remember his face, although the dawn light made that unlikely. I was aware I had three rounds in the pistol… I was also aware this didn’t matter. Luck gave me the first shot, but that’s all I’d get. He had the machine pistol.

“My shot hit him either high in the chest, the throat, or the face.”

Hillerman stepped on a landmine during a firefight with Nazis somewhere in the French countryside and was very seriously wounded. He lost the sight in one eye and part of his left foot and suffered from his wounds the rest of his life. But, in the spirit of his mother’s advice, this did not disappoint him—in fact, he characterizes it as the grunt’s beloved Million-Dollar Wound, the one that absented him from the remainder of the war and likely saved his life.

Hillerman’s long and painful recuperation in the field hospital in Aix-en-Provence fills the book with the hilarious, perverse black humor that forever afflicts and comforts those who are traumatized together:

“This ward had a tradition that no patient would be sent off to surgery without his fellows gathering at his bedside to hold a wake. The commissioned medical staff forbade this custom as insulting to them and contrary to good medical practice. However virtually everyone in the ward was a combat infantryman (the two exceptions were a tanker and an artillery forward observer) and the wakes went on anyway after the nurses had left. At these wakes, ambulatory patients would gather around the bed of the fellow due to go under the knife, discuss his character, and regale him with awful stories of ineptitude in military operating rooms (wrong organs tinkered with, arm removed instead of leg, and so forth). They would also establish ‘dibs’ on his various possessions in the event he didn’t come back alive and compose a letter to his family describing his sins and shortcomings. The only nurse who didn’t consider this tradition barbarous was an old-timer captain. She thought it was an antidote against self-pity—the worst danger in any ward full of badly-damaged young males.”

After the war and his slow recovery from his injuries, Hillerman worked as a journalist into the early 1960s, then decided to write more lasting prose. After earning a master’s degree he became a journalism professor at the University of New Mexico, where he taught from 1966 to 1987. During that period, he finally had the time to devote himself to writing. Eventually he penned 18 books in his Navajo series, which became worldwide bestsellers.

Hillerman won France’s esteemed Grand Prix de Litterature Policiere award. The Western Writers of America gave him the Wister Award for Lifetime Achievement. He served as president of the prestigious Mystery Writers of America, received that organization’s Edgar Award, and was named one of mystery fiction’s Grand Masters. The Tony Hillerman Prize, co-sponsored by Wordharvest and St. Martin’s Press, is awarded annually to the first-time author of a mystery set in the southwestern United States. Seldom Disappointed won both the Anthony and Agatha Awards for best nonfiction.

All that started when he encountered the tribe and its ways one fateful day in 1945:

“We finished the U.S. 66 part of the drive mostly in moody silence, turned off at Thoreau onto what was then a dirt road, and headed north toward Crownpoint, the Chaco Canyon country.

“And fate.

“Just south of Borrego Pass, a dozen or so horsemen emerge from the pinons up the slope. I stop and watch them cross the road ahead and disappear down an arroyo.

“We had been driving through Navajo Reservation land for hours, seeing Navajos who, to no surprise to a kid raised among Indians, dressed just like rural folks everywhere else. But these riders were obviously dressed for a ceremony, and the leader of the group was carrying what looked like a flag of some sort on something which, had he been a Kiowa or a Comanche, I would have called a ‘coup stick.’ I was immensely interested and curious.

“The well site where we eventually unloaded our cargo was near (five miles is near out here) the place of a white rancher. He rode up on his horse to find out what’s happening. I ask him about the group of horsemen. He tells me the delegation I saw was the ‘stick carrier’s camp’ bringing some necessary elements to an Enemy Way ceremony. He’s heard this was being held for a couple of Navajo boys just back from fighting the Japanese with the Marines. The ceremony was an Enemy Way to cure them of the evil influences they’ve encountered being involved with so much death, and to restore them to harmony with their people. I keep asking questions. He says why not go see it. They last about nine days and if the stick carrier was just getting there today it would still be going on through tomorrow night. Would I be welcome? Sure, he says, if I don’t drink whiskey and behave myself.

“Thus I got to see a wee bit of an Enemy Way without knowing what I was watching nor that the memory of it would provide the best section of my first novel.”

The Navajo characters Hillerman subsequently created, especially Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, his Navajo Tribal Police protagonists, are both noble, driven investigators determined to seek justice for the dead. Their stories all have several things in common—the rectifying of a blatant injustice done against the context of a deeply-wronged people; a deep and satisfying look into the beauty and balance that suffuse the Navajo culture; and a strong resistance to creating two-dimensional, stereotypical characters. Reading Hillerman’s novels guarantees that you’ll meet people and go remarkable places you’ve likely never before encountered.

Through this long series of mysteries, written over the course of 36 years, Hillerman slowly became America’s most original detective novelist. He took an ignored, oppressed, uniquely American group of people and humanized them. He created an entire self-sustaining fictional world based on the native culture of the real Navajos. He worked from the interior out when he built his symbols and his characters. He set his novels in the Four Corners region of the Navajo Reservation, a place so compelling that it became a character itself in his books. Most importantly, he transmuted the patience, fairness and harmony of Navajo life into the character traits that his protagonists use to solve his mysteries.

Inescapably, Tony Hillerman gradually became America’s version of the greatest and most well-known of all mystery writers, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Without question, Doyle created the most iconic detective that exists in fiction. To solve crimes, Sherlock Holmes uses his mind- along with a few primitive forensic science techniques—rather than brute force or violence. In Doyle’s singular canon of 56 short stories and 4 novels, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson became not just western civilization’s iconic solvers of crimes, but the prototypical fictional role models for the world’s emerging modernity. They exemplified modern, logical and scientific man by relying on science and ratiocination to solve life’s mysteries, rather than the murky dogma of the church or the trope of the lucky hunch or the dogged persistence of the archetypal police investigator. Instead, Holmes and Watson did something no one had done before—they found the modern material world sufficient to explain itself. In their creation, Doyle remade our view of ourselves and the world we inhabit.

In the Hillerman canon, the same thing occurs—only Leaphorn and Chee, our American Holmes and Watson, use not just modern logic and ratiocination, but powerful elements of Navajo myth and mysticism.

The younger Jim Chee is a Navajo medicine man in training, learning the healing ceremonies and sings that will carry on his tribe’s ancient traditions. Despite his modern university training, Chee believes in something beyond this physical world, and he studies the Navajo cosmology with deep respect and belief. Joe Leaphorn, Hillerman’s elder detective and the Holmesian figure in his novels, is a skeptic who believes mostly in what his senses tell him. Leaphorn and Chee together understand their culture’s belief systems and how they work in the modern, rational world. Because Chee’s faith and Leaphorn’s doubt often combine in the novels to produce the solution to the book’s central mystery, Hillerman is showing us a uniquely post-modern view—that modernity, technology and science do not necessarily supplant or obviate belief. In fact, Chee doesn’t even appear until after the fourth Navajo novel, when Hillerman realized that to truly tell the story of the Navajo belief system he needed a character who subscribed to it.

Sir Arthur did something very similar, by contrasting pre-modern beliefs and superstitions against the intellectual precision of modernity. With Holmes and his observational genius, the intellect and the rational mind always trump the unknown, in the same way that modern science has slowly supplanted and displaced superstition and religious dogma.

In The Hound of the Baskervilles, Holmes investigates the mysterious passing of Sir Charles Baskerville, scared to death by a ghostly hound that hunts down and dispatches members of the Baskerville family. Doyle based The Hound of the Baskervilles on the legend of Richard Cabell, a squire who lived in the 1600s in Devon, England. In the local myth, Cabell haunted the English countryside after his death, accompanied by a baying pack of ferocious hounds. In the novel, Holmes not only solves the crime, but also dismisses and dispels the myth by using his unique brand of science-based observation. These kinds of superstition-killing stories made Sherlock Holmes into an enduring global archetype. Doyle and his characters Holmes and Watson sometimes even get credit for helping to usher in the age of rationality, standing historically as they do at the end of the reign of superstition and the beginning of the reign of science.

The power of the work of both Hillerman and Holmes comes from their willingness to deal with the central human question—what does death mean in a scientific world? The exploration of this profoundly important conundrum doesn’t happen much in literary fiction these days, with a few exceptions. Instead, it happens primarily in genre fiction, where social realism is still resoundingly alive, where writers explore those issues and where actual death occurs.

Death is the central mystery we all grapple with in life. It explains the growing, even explosive, popularity of mysteries and the increasing tendency for even our great literary novelists—Jim Harrison and Cormac McCarthy, to name just two of many who’ve begun publishing mysteries—to write socially realistic genre novels freighted with actual meaning.

Because of this trend, the old literature vs. genre fiction conventions and definitions are fast fading away, losing their utility and their cachet. If you’re a librarian or a bookstore owner, where do you shelve a George Pelecanos or a Richard Price or a Dennis Lehane or a James Lee Burke book? Where do you put McCarthy’s most recent novels? Maybe, to replace the outmoded old Literary vs. Genre sections, we need two new categories in our fictive universe—novels that deal directly with Death and those that Don’t.

All the great mystery novelists—Poe, Doyle, Chandler, Hammett, Sayers, Hillerman, Burke—explore the meaning of violent death in a society devoid of belief. What does death mean? each of them asks. In an industrial, rational and unbelieving culture, does it have any meaning at all?

The great mystery novelists all answer in their own ways. For Poe, death was a horror story, beyond endurance and forever terrifying. For Doyle, violent death is a mystery that demands a rational and therefore at least somehow ultimately comforting solution. For Hillerman, murder is a travesty, an insult against the harmony inherent in the universe. It demands balance be restored and justice be done. Hillerman’s autobiography and his powerfully drawn novels teach readers that the world is not just a rational, mechanistically material place, and that understanding its mysteries requires something beyond a purely rational mind—it requires a soul.

Ultimately, the great mysteries don’t just entertain us, they explore the meaning of death in a culture that’s losing its religion. They represent our deep collective human need to explore and understand what’s next. That’s the source of their endurance, their popularity and their continuing cultural relevance. The best mystery writers show us that we all stare into the depths of that sacred canyon, and what we see there looks back at us.

David Langness is a writer, literary critic and patron of Navajo art who lives in Northern California.