Despite what a growing (if dissonant) chorus of literary critics might have you believe, you do not have to choose between the novel and the memoir. Neither will supplant the other, and there will continue to be published fine and not-so-fine examples of each. Yet the war rages on. The novel is declared dead. Again. This time, the memoir is supposed to have killed it.

Civil wars are historically among the most bloody, and this one’s no exception. Though plenty of writers have written good novels as well as first-rate memoirs, the fire coming from both directions is less than friendly. On one side is David Shields and his starving army. In Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, he writes, “Novel qua novel is a form of nostalgia,” and, “The kinds of novels I like are ones which bear no trace of being novels.”

Them’s fightin’ words, and Lorrie Moore, for one, is not going to take them sitting down. Author of last year’s much-lauded but actually insubstantial novel A Gate at the Stairs, Moore takes to the pages of The New York Review of Books to launch a counter-attack under the guise of considering three recent memoirs. Moore trades in Shields’s laconic, aphoristic style for something more shrill and sarcastic, but the thrust of her argument mirrors his exactly. In her conclusion to the analysis of one memoir, she argues that the writer would have done better to write a novel instead: “a novel, where such inner lives can indeed be recreated or at least imagined with specificity: ironically, the genre of the novel, with its subtle characterizations and rich and continuous dreamscape, remains a kind of gold standard for a genre that may be usurping it.” This “gold standard” is, of course, her own, as she’s just defined it. In other words, the memoirs that she likes are ones which bear no trace of being memoirs.

Moore isn’t alone. There is a certain, unfortunate, and oft-promulgated school of thinking that a memoir should be nothing more than a truth-novel. That’s what I was taught in graduate school, until I took a workshop with Phillip Lopate, who argues persuasively for the conventions that are indigenous to memoir and essay. In a “Comments on the Form” essay for the nonfiction literary magazine Fourth Genre, Lopate deplores the chestnut, “Creative nonfiction is the application of fictional devices to memory.” This denies nonfiction its special access—indeed its inalienable reliance on—meditation and contemplation. The memoirist doesn’t simply recount and recreate her experience as if she’s the first-person narrator of a novel that happens to be true. She also makes sense of that experience. As Lopate writes, “There is nothing more exciting than following a live, candid mind thinking on the page, exploring uncharted waters.” A novel’s protagonist may be captain of her ship, but a memoirist, a good one at least, is also cartographer.

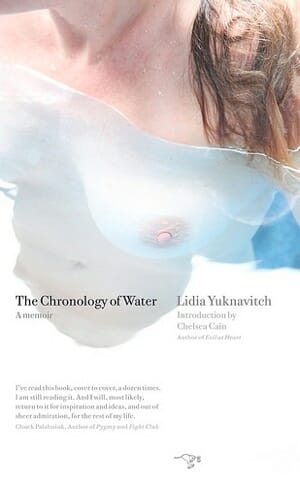

Speaking of water … as its title suggests, Lidia Yuknavitch’s fierce new memoir, The Chronology of Water (blurbed by Shields, among several eminent authors) takes place entirely off-shore, metaphorically speaking. Nothing about her life has followed the map. If the memoir has been under attack recently for recounting the same sad stories again and again, Yuknavitch has hit the tragedy trifecta. Her tale comprises incest, addiction, and a dead baby—plus, she’s a former athlete and occasional lesbian. Defenders of the memoir genre often point to its outliers, the ones doing something different, telling that one story that still hasn’t been told. No such luck with The Chronology of Water. But perhaps this hat trick of woe also would have made it impossible for Yuknavitch simply to novelize her past, as Moore might have advised. No fictional protagonist can realistically overcome that much. So, memoir it is.

One thing memoir does share with the novel? It isn’t what you say, it’s how you say it. So, sure, other people were sexually abused as children. Others have succumbed to the numbing powers of illicit substances. Babies die every day. And plenty have written about it. While I can’t say Yuknavitch does it the best, because I’m rarely moved to read an incest or addiction or dead baby narrative, and thus have little basis for comparison I will say this: She does it damn good.

I’m using damn good with intention. This book is good, no doubt, but it is also damning. Without fashioning itself as a critique of society, but just by telling a story of one woman, of one daughter, of one swimmer through water and life and words, it excoriates. Yuknavitch speaks frankly of crimes which most of us would have preferred to call unspeakable and leave it there. These many crimes of family go unpunished, and forgiveness fails, not because it isn’t granted but because it isn’t enough. How could it be, when time and again, the architect father grossly violates, and the real-estate-agent mother grossly neglects? In one excruciatingly vivid scene, the father drags his family up a deadly snowy Mt. Rainier to cut down a Christmas tree. Lidia falls behind, bluely hypothermic, and is (for once) tenderly ministered to by her mother. When he finally returns with her silent, shivering sister, she “looked like her legs didn’t work right.” Yuknavitch has this terrible talent for choosing the right, most crushing detail. Witness the mother after she tries to off herself with vodka and pills while Lidia quite literally stands by, tears and questions in her young eyes. Her mother’s terse response: “Stay away; this isn’t anything for you. I’m not talking about anything.” Why make up dialogue when you have material like that?

The memoir-as-truth-novel would, at that point, simply move on to the next chilling scene, perhaps one that shows how the mother’s suicide attempt has damaged the daughter. But Yuknavitch exploits that ruminative potential of the genre by moving from the child’s perspective to the adult’s, wherein she does the doubtlessly painful work of locating her mother within herself: “I didn’t know yet how wanting to die could be a bloodsong in your body that lives with you your whole life. I didn’t know then how deeply my mother’s song had swum into my sister and into me….I didn’t know we were our mother’s daughters after all.”

Damn.

The metaphors of water and swimming recur meaningfully throughout the book, which is organized into more than 50 short, titled chapters. The ordering of events is liquid, recursive. This is true to Yuknavitch’s lived experience, which moves, but not strictly forward. It swirls, clouds, pools. A swimming scholarship takes her away from an oppressive household, but she isn’t yet saved. She loses the scholarship and obliterates herself with drugs and sex. Even as, ultimately, Yuknavitch finds her “twin” and her “tribe” in a community of fellow writers, her family by birth cannot be totally renounced.

Among the other liberties of memoir is the ability to be endlessly multifarious. The narrative needn’t be unified and the protagonist needn’t be characterized as internally consistent. To make them so would be dissembling, for who among us takes just one shape? Yet we are still one person. Like molecules of water, different moments of our being scatter and stick, stick and scatter. For Yuknavitch, this paradox is explored through her descriptions of sex, sexuality, and the body. These take up a lot of space. She has one body, a swimmer’s body, but that body expresses itself in every conceivable way. It moves through many waters. There is masturbation close on the heels of abuse. Consensual sex that occurs within the bounds of a conventional marriage turns out to be grotesque, while sex that seems impersonal, even random, sex where no love lives but only a lusty curiosity, turns out to be healing and true. Nor do these revelations follow any kind of normal or expected trajectory. Yuknavitch gives new, rich meaning to the by-now-familiar idea of a fluid sexuality.

Sometimes, the meaning drowns in all that water. Everything about the book is wet and slippery. Usually, that’s a good thing, a kind of wild antidote to the current vogue for restrained, clipped prose. But Yuknavitch occasionally repeats herself, a reminder that the book had many incarnations, first as a short story. We are sometimes, clumsily, given the same background info in adjacent chapters. This could have been tidied up, as could have longer, stream-of-consciousness sections that lack the kind of verbal surprise that we’ve become accustomed to. Good things start to happen to Yuknavitch, and that’s, well, good. The way writing finally connects her to something beautiful in herself and in the world—that’s a story worth telling. But too much is told of how her writing wins external approval, of how, for instance, to her almost too-naïve astonishment, Ken Kesey, her first writing mentor, actually engages her intellectually instead of sexually. By that point, though, what matters is how writing transforms her vision of herself, and we don’t see this as clearly. Yuknavitch has the rare gift of writing about sex interestingly, without euphemism, by staying firmly tethered to the physical. The same goes for her descriptions of swimming. Strangely, she is unwilling to do the same with writing, which is no less an action. Instead, suddenly and unbecomingly coy, she ducks under. I wanted to watch her body making sentences.

One senses a kind of defiance in regard to those sections that puddle. Yuknavitch refuses to dam the flow, and the book is mostly the better for it. In fact, the book is what it is because of this defiance. With all its section and chapter titles, its patterns and deliberate, splendid, terrifying juxtapositions, The Chronology of Water is undeniably crafted. Yet a certain artlessness persists. This is memoir in the true sense of being written as remembered. Many of Yuknavitch’s contemporaries flank their material, so limited by what can really be recalled, with research, context, documentation, illustration. Not so here. Alternatively, Yuknavitch reflects on the nature of memory—how it is limited, self-justifying, and mutable—and how it coincides, or doesn’t, with truth and its telling—in other words, with art. Often, after recounting a scene from her past, she admits that it didn’t happen in just that way. But this is no mere gimmick. After brilliantly recounting a particularly dramatic moment in a particularly dramatic relationship, she reveals, “That’s a great line, isn’t it. That’s a great ending. But lives aren’t James Taylor songs, and girls like me don’t just run off into the snow and go away.” A point well worth making.

On the same relationship: “I remember looking at the top of his head and thinking look, it’s an angel, and my very next thought was, spit on his head. I told you, I don’t know why. Why did I eat paper as a kid when I was scared?” In this way, Yuknavitch slyly confesses her inability to interpret, but, in doing so, offering an interpretation just the same—when it comes to some parts of our past, there is no recognizable order. Sometimes, there are no answers. Here are moves a novelist can’t make.

There’s a kind of humor here, too, that would be out of place in fiction because it emerges from the need to see things as they are. At times, it’s simply diverting: “Campus police showed up and wrote things on small pieces of I’m not really a cop paper and handed them to us and told us to go home. After they left we ate them.” Other times, when Yuknavitch turns the humor on herself, the mood darkens: “I just got louder and bigger and hornier and more horribly chaotically blond.”

There are, of course, conventions and devices most at home in a novel. Certain kinds of irony and most kinds of suspense do not belong in memoir. In nonfiction, the unreliable or naïve narrator irks; archetypes and symbols risk seeming, at best, contrived, and at worst, inauthentic. The novel’s exploitation of such emblems is perhaps what Moore refers to by its “rich and continuous dreamscape.” As for her idea that “subtle characterizations” are the exclusive province of the novel, well, I’m not sure how she came up with that one.

The Chronology of Water doesn’t transcend or subvert its genre. Yuknavitch addresses some of the most recognizable, some would even say clichéd, tropes of the contemporary memoir. She flirts with sentimentality and just barely skirts the kind of therapeutic narrative arc that the memoir police so despise. Memoirists, ipso facto, face charges of self-involvement. Yuknavitch is nothing if not deeply involved—immersed—in her own life, body and native waters. So much the better.

Amy McDaniel helps run the Solar Anus reading series in Atlanta and contributes to HTMLGiant. Her work has appeared in Tin House, The Agriculture Reader, PANK and others. She is the author of a chapbook, Selected Adult Lessons (Agnes Fox Press). In August, she is off to Bangladesh to teach creative writing and literature at the Asian University for Women.