Dennis Cooper’s fictional world is a treacherous slope of time-shifting narratives and secret mental passageways, designed to seduce and then ensnare readers. Groping around his existential darkness is oddly pleasurable for those of us fascinated by writing that explores intense eroticism and violent acts of cruelty exposing the extremes of human nature.

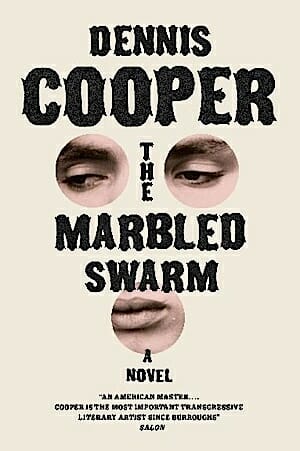

In his new novel The Marbled Swarm, Cooper leads us through a labyrinth of memory and cannibalism, lighting the way with some of the most gorgeous prose of his estimable career. Sloppily labeled a “cult writer” after a productive career that includes many kinds of novels (including the highly praised The George Miles Cycle), along with poetry, and nonfiction, Cooper gives us an intriguing and fresh direction in this concise new work. We may be feeling the influence of his new residency in France, where acclaim for his writing made him the first American to win the literary prize the Prix Sade, for his 1996 paean to online sex chat rooms, The Sluts.

Swarm presents us with the narration of a wealthy aristocrat seducing a family into selling him their crumbling Chateau Etage, tucked away in the French countryside. Cooper turns the classic gothic premise, used by everyone from Wilkie Collins to Jennifer Egan, on its head, chaperoning an orgy of Dickensian characters, each whispering naughty secrets in his ear.

Without revealing too much of a complicated plot, an elder son of the chateau’s resident family has mysteriously died, and his subsequent ghostly reappearance leads the new owner and the reader into a maze of secret passageways and peepholes throughout the house. Hiding behind walls, the new owner obsessively watches Serge, the family’s nubile younger son. Serge pants for experience and escape, and seems willing to do anything to get it.

The gothic setting and shenanigans perfectly set up Cooper’s sharp, macabre humor:

“Still, even a mild summer day is no preservative, and dead boys aren’t exactly a wheel of brie, however much they might smell the same eventually.”

Cooper’s atmosphere feels timeless, despite the odd reference to modern-day technologies like Facebook and iPhones. Cooper relishes pulling the rug from under the reader, forcing a stumble around another dark angle, into an unexpected connecting narrative. Voyeurism telescopes into a son’s desperate hero worship of his aristocrat father, a yearning for acceptance that raises the book from snuff-film script into coming-of-age memoir.

Cooper unites disparate story strands through an evocative Parisian setting and the use of a secret seductive language the father teaches his son as a means of entrepreneurial advantage. The father-son code, termed “The Marbled Swarm,” represents the safety and acceptance a father tries to instill in his son, even though the son later manipulates their shorthand for his own grislier desires. Isolation and parental mistakes are hardly new themes for Cooper, but here he shades and morphs them, allowing only oracular glimmers to show through the lush wordplay:

“As much as I would love to overrule some chums who’ve called my voice a kind of fancy drainage ditch through which my brilliant father’s voice forever sloshes and evaporates, to ask myself to replicate his words verbatim would be like asking you to travel to Miami on the broken champagne bottle that baptized the ship that could have sailed you there in style.”

Cooper’s narrator also explores the latest twists in the evolution of modern sexuality, refusing to be defined or contained by a lifestyle label:

“Now, were I gay or, if you insist, entirely gay, I would have … well, you tell me. I’m not gay enough to know.”

This winking quality gives the novel a galloping, almost farcical energy at times, especially after our unnamed narrator takes over his father’s business and hooks up with a cadre of young cannibals who proceed to make dinner plans (or not) for someone’s younger brother. The funhouse Cooper has built for these intense emotions of devotion and cruelty, of willful illusion and hypnotic truth, morphs as often as the narrator. The plot journeys with the narrator from the station of an established aristocrat to a lost and confused son constantly yearning to master a language and morality his father taught him.

The dirty secret to Dennis Cooper’s esteemed legend (despite his polarizing subject matter of sodomized boys, cannibalism, and pulverized human flesh) is simple—nobody else writes like him.

The Marbled Swarm proves it again, in a novel blending surprising wit, bleeding messy humanity and soul, and dark beauty. The book nudges readers closer to identifying with the violent extremes of our very human nature—Cooper’s ultimate theme. For Cooper, carnal lusts point the way toward the real truths of our deepest desires. Ironically, a novel dense with landscapes of language and satire offers a wholly stark depiction of our frailties as people.

After years of releasing short stories, poetry collections, and anthologies of nonfiction writing, Cooper returns to the novel. Why? In his recent “Art of Fiction” interview with Ira Silverberg in The Paris Review, Cooper admits:

“If you’re interested in writing in chunks or paragraphs, and if you want your work to be published in a way that as many people as possible will have the opportunity to find it, you write novels. I’m not interested in the stuff of conventional novels. I’m dedicated to writing about pretty specific things, in the hope of coming to a point where I feel no desire to address them anymore.”

On those terms, The Marbled Swarm takes well-mastered conventions of the novel and classic storytelling and mutates them. At a time when much serious literary fiction is whittled down into bite-sized morsels for easy digestion, Cooper’s reengagement with a stylized long-form work (earlier novels, such as Closer and Frisk, stand out for their lean spare style) feels like a challenge to his readers: Stop. Focus. Engage.

We live today in a culture dominated by mistrust—for government, for religion, for institutions of commerce. Many people look toward the edges for new heroes. Punk rocker Patti Smith, who extolled the virtue of living outside of society, now claims a National Book Award for a memoir modeling just how she accomplished it.

The same impulse keeps Dennis Cooper’s long-held ideas about gender and sexuality—and the chaos that may result with denied urges—in vogue. We witness yet another sex scandal on yet another college campus, with students rioting in support of decisions of questionable morality by football coaches. We see yet another set of politicians scramble for rationalizations to our problems (did anyone ever imagine that “Oops!” could be a campaign slogan?). Too often, we turn our eyes from anything that contradicts our beliefs, maybe simply to avoid the glare of truth.

Cooper’s status as an underground renegade of experimental fiction doesn’t reduce his talent or the brilliance of his dark views. He is a passionately humane writer. We need his voice now more than ever.

Mark Snyder is a Brooklyn-based writer. His new play As Wide As I Can See will open off-Broadway this winter.