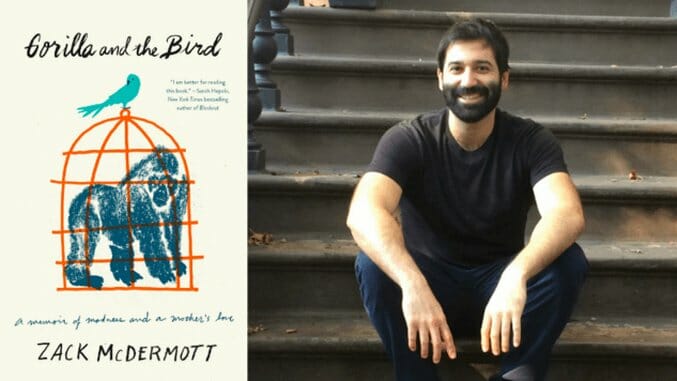

In Gorilla and the Bird, Zack McDermott Challenges the Stigma Surrounding Bipolar Disorder

Author photo by Aurélie Hagen

Zack McDermott had his first major manic episode in over five years at a Taco Shop in his hometown of Wichita, Kansas. As the psychosis took hold, he laughed at patrons to their faces, inquired about purchasing his order via Apple Pay—something he knew, even in his semi-lucid state, they would not have—and, eventually, screamed obscenities at an employee while lying flat on his back in the rain-soaked parking lot.

Which is when his producers stepped in.

The cinéma vérité camera crew filming him at the moment (for a documentary and a series of mental health and criminal justice reform PSAs) must have added an absurd element that McDermott, a former lawyer turned comedian-cum-memoirist-cum-mental health advocate, can surely appreciate. His psychotic breaks tend to make him believe he is being filmed for a TV show, a delusion known as the Truman Show delusion. His request to use Apple Pay was a literal reality check; if the Taco Shop cashier said yes, then McDermott would have known the scene was fake. All this took place while the real film crew kept rolling.

“I got to see myself shouting at the wind,” McDermott tells Paste in a phone interview.

A few years before that manic episode, a more severe break earned McDermott his bipolar diagnosis.

As McDermott describes it at the beginning of his new memoir, Gorilla and the Bird, he had gone on a tear for the delusive cameras throughout Manhattan’s East Village, careening through traffic, replacing a soccer goalie and encouraging his teammates to shoot on him—in a Scottish brogue—before jogging around the field bare-assed. His manic trek ended on a subway platform—stripped down to his underwear, tears streaming down his face—from where two NYPD officers took him to Bellevue Hospital.

“I was really grateful for it, actually,” McDermott says about the more recent Taco Shop break. “It was like, ‘Okay, chin check, buddy. Got a little too close to the sun again.’” The event was a reminder that bipolar disorder is chronic, but also that it can be managed. He had been pushing himself too hard, working 15-hour days and showing some light signs of what could devolve into mania.

McDermott had lasted so long between manic episodes, because when he finds himself in a “Danger Zone” spot, he knows what to do: “Ativan, ice your neck, take a Risperdal, go to sleep, clear your calendar the next day.”

But before he had the playbook down pat, it was a long and savage process of extremes, of manic episodes that burnt through his brain like “wildfire.” The support of those around him, including his mother—the titular bird to his gorilla—and a regiment of psychiatric medications and social strictures—sleep, no weed, don’t get fucked up every night—have helped him to manage his illness as well as he does. Now, he can see the ambush looming.

It’s this basic understanding of the signaling symptoms and preemptive treatments of the disease—something taken for granted with most maladies—that McDermott hopes he can engender in the greater population. His memoir, which combines the brutal realities of his experiences with gallows-dwelling white trash humor, will hopefully be followed by his current projects, a documentary and public service announcements.

“We need to embrace that there’s this thing called bipolar disorder,” McDermott says. “And in that embrace, what we need to do is be able to identify the symptoms. You need 80-90% of the population, if not higher, to just be familiar with and identify these symptoms.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-