Published last week, Black Panther #1 by Ta-Nehisi Coates, artist Brian Stelfreeze and colorist Laura Martin witnesses a prestige prose writer transitioning to comics work. Given that Coates was recently awarded the National Book Award and the MacArthur Fellowship/“Genius Grant,” it’s a newsworthy instance of the prose-to-comics phenomenon, but it’s hardly the first. The comics industry harbors a deep and symbiotic history with prose. Watchmen scribe Alan Moore and The Dark Knight Returns’ Frank Miller both drew heavily from novels, inflecting their comics with a reverence for Thomas Pynchon and Mickey Spillane, respectively. In recent years, award-winning books like The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon and The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz referenced the silver age super-science stories of ‘60s Marvel and DC comics, with the former even featuring comic book legend Stan Lee as a character.

Running parallel to these literary cameos, companies like Marvel and DC have gone out of their way to hire novelists to write comics. The controversial Identity Crisis (Brad Meltzer), Image hit Lazarus (Greg Rucka) and long-anticipated Fight Club 2 (Chuck Palahniuk) are all written by men who began their career writing prose fiction. This relationship even stretches back to when Ian Fleming adapted his James Bond novels for a serialized comic strip in 1957, and Naked Lunch author William S. Burroughs collaborated on a self-described “comic book.” But in the last two decades, the bigger comic book publishers have drawn more and more from that talent pool. Looking at the work it’s produced, however, leads to one question: why?

Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose most recent work can be found in The Atlantic and nonfiction book, Between the World and Me, has publicly discussed his love of comics, and he’s written extensively on how the medium—and superheroes in particular—shaped him as a writer and person. His actual work in the debut issue of Black Panther, though, illustrates the learning curve of seamlessly coordinating words and images. In the issue (which is admittedly of a higher quality than most first-time comics writers produce), he demonstrates a capability with narrative, but a timidity with the comics form. But in many other respects, he does shockingly well.

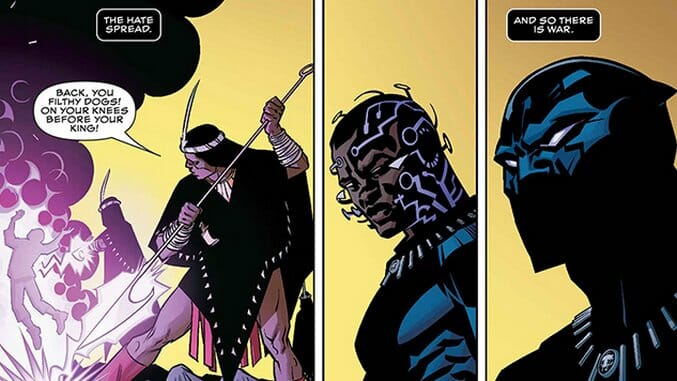

On a visual level, Black Panther’s pages lack an intuitive flow, hampered by arbitrary and haphazard layouts. Organizational issues aren’t necessarily the fault of the writer, especially in cases where the script is written more loosely for artistic interpretation. But storytelling dissonance is more pronounced in scenarios like this than when the comic is executed by a single cartoonist. Each panel here is treated as its own separate storytelling unit, captions carrying much of the narrative bulk instead of punctuating and guiding the storytelling (check out the third page for a caption-heavy example).

This issue is fairly common among comics written by prose writers crossing over to the panel. The Brad Meltzer-scripted Identity Crisis DC comic suffered similar issues, and captions have also dominated the brief comics sojourns of Stephen King (American Vampire), China Miéville (Dial H) and even Michael Chabon (The Amazing Adventures of the Escapist). For whatever procedural quirk, some books manage to avoid this, but it’s a common failing in this category.

An overreliance on text exposition is also a common stumbling block in the prose-to-comics transition. Wordy scene setting wormed its way into Joe Hill’s Locke & Key, Orson Scott Card’s Ultimate Iron Man and Harlan Ellison’s 7 Against Chaos. This is by no means a trap that ensnares prose writers exclusively, and a list of comics writers who suffer from this problem could fill a book, but it shows up in the work of first-time comics writers in higher percentages and to greater degrees.

Black Panter #1 Interior Art by Brian Stelfreeze and Laura Martin

Much to his credit, Coates doesn’t fall deeply into this hole, and he demonstrates a deference to Stelfreeze’s art. The writer keeps the captions, though frequent, to a minimum word count, and the dialogue, while sometimes superfluous, isn’t the pair of cement shoes that other writers fasten to readers’ feet. That said, much of Black Panther’s expository text is clunky—a surprise considering how lush and lyrical Coates’ prose is—and it doesn’t add or direct the narrative’s action in any way. It offers a contextualizing hand, but the story is left opaque enough that it ends up reading more like a lack of confidence than a necessary storytelling device.

A less common, but no less grating, technique that prose writers like to employ is the faux-formalism that’s found a home in the work of many popular post-2000 superhero writers like Brian Michael Bendis and Matt Fraction. The most recent example is Fight Club 2’s use of meta-sleights of hand (photorealistic pills or rose petals layered on the page and “over” the panels, inserted between the plot and the reader). There’s the sense that Palahniuk wanted to replicate the meta-techniques that fans enjoy in his prose, but other instances read more like attempts at formalism for its own sake. Fortunately, Coates plays fundamental licks in Black Panther instead of pursuing clever quirks, and the readability of the comic benefits greatly.

Coates and Stelfreeze’s work is particularly interesting in the tradition of prose authors turning to comics for the first time, as Coates manages to avoid falling into the same damning traps that many others have. But viewed within the totality of comics, it’s hard not to notice some of the problems that tend to accompany the prose-to-comics hurdle. The book lacks an immersive rhythm, and Stelfreeze’s role as co-writer isn’t on par with his staggering work as an aesthete. Black Panther #1 is filled with a number of beautiful individual compositions that, taken as a sequence, make for a choppy overall read. From a purely narrative perspective, the comic is incredibly intriguing; it decentralizes its title character and positions a pair of gay black women in leading roles, elevating it beyond most all of the Marvel pack. But the book still labors under considerable constraints of the superhero genre’s commercial apparatus, and leaves a seamless bridge between Coates’ lauded authorial prose just out of reach.