Cartooning Legend Bernard Krigstein’s Career Foreshadowed a Lethargic Comics Industry

The common influence between such benchmark comics as Sin City, Maus and Ghost World, Bernard Krigstein is your favorite artist’s favorite artist. Though his name is little-known to the average reader, he pushed the boundaries of what comics could be in their Golden Age, and his fine-art intentions have drawn comparisons to the literary ambitions of V For Vendetta and Watchmen writer Alan Moore. He also would have been 97 this week. In the face of censorship legislation, Krigstein was forced out of the industry at the height of his power, relegated to teaching high school art classes for the last decades of his life. While his abrasive attitude was no doubt a contributing factor in this development, his short-lived career still speaks to a recurrent problem in the comics industry, one as topical today as it’s ever been.

Even at the dawn of sequential art, Krigstein faced a harsh reality that’s remained consistent to today: the comics industry abhors change. This conservatism has taken various forms throughout the decades—the ‘50s endured the restrictive, short-sighted psychology of Fredric Wertham. The fight continues today as the medium faces hurdles to diversify its creators beyond a white, heteronormative male foundation. Like other media, the comics industry has rarely accepted those voices who sought to innovate within its panels—Krigstein is a testament to that unfortunate legacy.

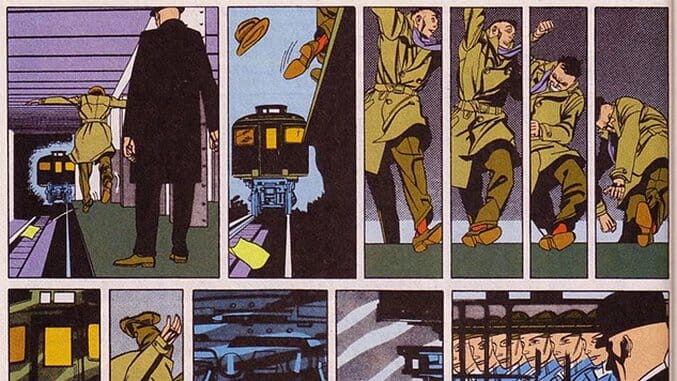

The Matster Race by Bernard Krigstein

Born in 1919, Krigstein spent the early days of his career working on short stories like “The Monkey’s Circle!” and “Eugene Vidocq…First Great Detective.” He signed his work as “B.B. Krig.,” recalling a nickname he picked up in the army: “ballbuster.” According to Maus creator Art Spiegelman, Krigstein was a formally educated painter, but he pursued comics to support himself. Realizing the potential of the form, he devoted his time and energy to expanding its boundaries.

Krigstein’s career was rocky; work was scarce and he bounced around from publisher to publisher, often saddled with assignments that didn’t allow him to fully explore the extent of his skills. Recounting his work for superhero publisher Fawcett in the late ‘40s, the artist described his output as “hackwork of the purest distillation,” and refused to even sign his issues. But he continued to publish at a variety of magazines—even contributing “Drummer of War” to DC’s Our Army at War anthology. Most of his works, however, were short-lived and are now long forgotten, though he did contribute to MAD during its heyday.

Krigstein would often balk at deadlines, slowing down his process by inking his pencils instead of handing them off to another artist. He once unsuccessfully tried to unionize comic book artists—a movement editors and publishers tend to frown upon. He eventually fell in with EC, a company most famous for its lascivious horror comics like Tales from the Crypt, where his ambition and singular style were encouraged. The publisher even allowed him to expand his opus, “Master Race,” from six to eight pages.

Running in the first issue of EC’s new suspense thriller anthology, Impact, “Master Race” tells the story of Carl Reissman, a Nazi who works in a concentration camp only to escape to America and anonymity. Today, the topic of Nazis and Nazism is common fodder for pop-culture, but in 1955, Krigstein was touching on something recent and controversial. Released the same year as “Master Race,” Alain Resnais’ documentary Night and Fog dealt with identical subject matter, “an almost unheard-of theme in Western mass media.” The film was so controversial that West Germany convinced France to pull it from the Cannes Film Festival.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-