Norwegian Cartoonist Steffen Kverneland on Biography, Obsession and The Scream Painter Edvard Munch

Published in North America in May by Abrams/SelfMadeHero, Munch is the fat, titular biography of the Norwegian artist best known for his painting, The Scream. Its creator, Steffen Kverneland, is scheduled to appear at this year’s Small Press Expo next week in Bethesda, Maryland. Also a Norwegian, the cartoonist researched, wrote and drew every page on watercolor paper over seven years, resulting in a book intensely invested in its subject. Far more interesting than the average comics biography—of any type—it also manages to achieve this feat without innovating on the format or content. All the dialogue comes either from Munch’s own written words or from those of his contemporaries. The book utilizes a combination of meticulousness and free-spiritedness (Kverneland himself appears as a character, boozing it up and talking about his difficulties with the book) that is unusual, to say the least. Kverneland answered Paste’s questions via email, patiently delving into a good bit about his career in the Norwegian comics scene.![]()

Paste: You seem like a bit of a comics prodigy from what I know about your background. Did you always draw? Do you make a living from comics?

Steffen Kverneland: Thank you. I guess all children draw, and I’m one of those who never stopped. I got into comics as a child, even before I could read. Actually I learned to read from Donald Duck. I started doing comics and other drawings already when I was a child. Later on I also started doing fine arts stuff, painting myself through the Renaissance, realism, impressionism, pointillism, cubism, expressionism and surrealism. All the while drawing comics as well.

In the ‘90s in Oslo, I tried to pursue three separate careers simultaneously: as a fine artist making paintings and drawings, as an editorial cartoonist doing political satire (for the money) and as a comic artist (both commercial stuff, like the Norwegian edition of MAD, and my own experimental comics). When I discovered Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW magazine, it made a huge impact on me. Suddenly, everything was possible in comics; there were no limits to how far you could go artistically. It suddenly dawned upon me that I could combine my three separate careers in clever highbrow comics with radical graphics.

At the same time, I became part of a literature milieu, largely consisting of literature students. They started the highbrow literary magazine Vagant, which is still going strong. They asked me if I wanted to do some comics as well as illustrations for them. At the time, I was really into modernism and avant-garde, like [Samuel] Beckett, absurdism, William Burroughs (especially his cut-ups), stuff like that and RAW magazine. So I did some cut-ups from literary texts, mixed them up and drew some naked politicians uttering these mashed-up fragments and subversive, anarchistic stuff like that. It was all very spontaneous and improvised and great fun to make. Later, my works became increasingly refined, controlled and less nonsensical, and the cut-ups were chosen deliberately, not by chance. But I stuck to the doctrine/dogma of not cheating with the quotations; they had to be accurate.

It’s very hard to make a living making comics in Norway, so I’ve always subsidized my comics by doing illustration, which pays better by far.

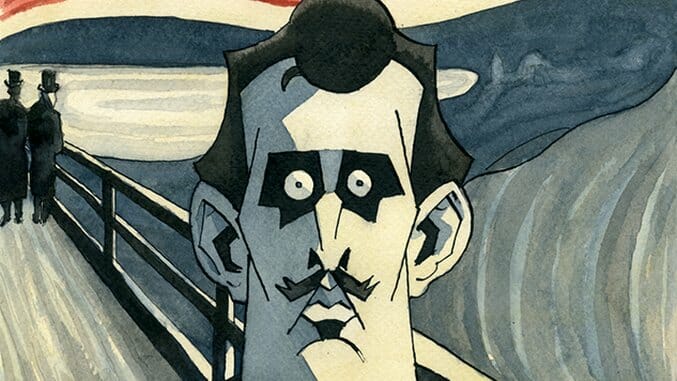

Munch Cover Art by Steffen Kverneland

Paste: Did Munch start out as a collaboration with Lars Fiske and then grow into a longer work? Did you start from scratch when making the full book?

Kverneland: I made Munch on my own, but the presence of Lars Fiske is very evident in the book. In 2004, Fiske and I released our 180-page collaboration Olaf G., which was a comic biography combined with a nerdy and boozy gonzo travelogue. A lot of the storytelling devices and techniques used in Munch were developed in that book. We went to München and Bavaria in search of the Norwegian master illustrator Olaf Gulbransson, who was headhunted to work for the excellent German satire magazine Simplicissimus from 1902 until he died in 1958. We both wrote and drew the story, and the collaboration was great fun. The book was published in Norway, Sweden and Germany, and was supposed to be published by Fantagraphics, but was “postponed indefinitely” after the tragic demise of Kim Thompson.

We wanted to work together again, but not as tight as we had done in Olaf G., so in 2006 we published KANON no. 1, which was meant to be an annual book containing new works by Lars and me. He made chapter one of what was to become the graphic novel Herr Merz (a biography of the German dadaist Kurt Schwitters), and I made the first chapter of Munch. From Olaf G., we were used to having the other guy as a sidekick, so that instead of an old-fashioned, all-knowing omnipresent voice-over, we could do the text as dialogue, making it less stiff and artificial, more alive. So we just imported that meta-layer into our new works.

Paste: Is Munch’s work as omnipresent in Norway as it is in the United States, with Scream posters and blow-up dolls decorating college dormitories? What’s his place in contemporary Norwegian culture?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-