Why The Eisners Need to Show Webcomics Some Love

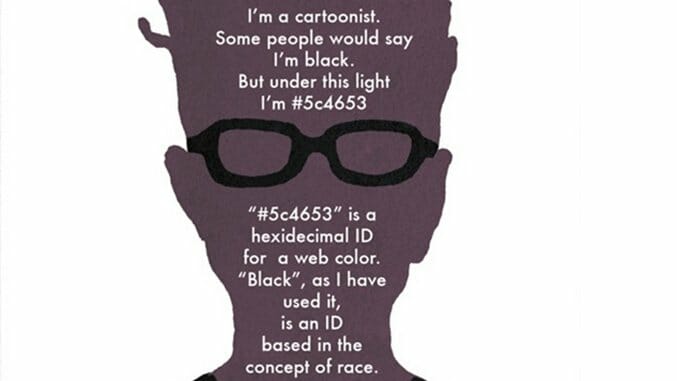

Cover Art by Ron Wimberly From His Comic, Lighten Up

In an era when the most well-known awards are prompting hashtags, and less recognizable cousins are struggling with issues of their own, the announcement of this year’s Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards prompted that awkward mixture of excitement and dread that’s becoming more and more familiar for many people in creative industries. Though the Eisners have not historically practiced the same intense level of exclusionary politics as Angoulême, many fans and pros alike worry about the results of an industry-driven nomination process; the inherent design can neglect less mainstream players, and result in a narrower field of nominations.

By and large, the nominees this year do reflect a relatively wide swath of talent. And while there are some expected names on the list, it’s not nearly as predictable as it could have been. That said, the nominations illuminate one troublesome topic—the Best Digital/Webcomic category. This isn’t to say that the nominees aren’t deserving—they absolutely are. But there is a problem when the Eisner committee conflates “digital comics” and “webcomics.”

With the advent of comiXology and the subsequent creation of programs like Marvel Unlimited and DC’s Digital First titles, it’s clear that the industry has embraced the paperless future of comic publishing. But digital-first comics share far more in common with their printed counterparts than not. With the exception of double-page spreads and the occasional large-panel layout, the formatting of a paper comic is similar enough that the average reader would be hard-pressed to find the divergences. Fresh Romance, Bandette and The Legend of Wonder Woman are perfect examples of how digital comics can (almost) seamlessly transition from screen to paper without significant impact on readability. As the term “digital-first” implies, these books are typically designed with the future leap to print in mind. They’re worth celebrating as digital successes, remarkable for their foray into a new medium as the industry continues to change.

But these are not webcomics—sequential art posted on the internet for consumption on, and only on, the internet, rather than crafted into what amounts to an advance e-book edition. That may seem like pedantry or semantics, but there is a very important distinction between something that is formatted as a digital reading experience and something that is posted online for sole on-screen consumption.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-