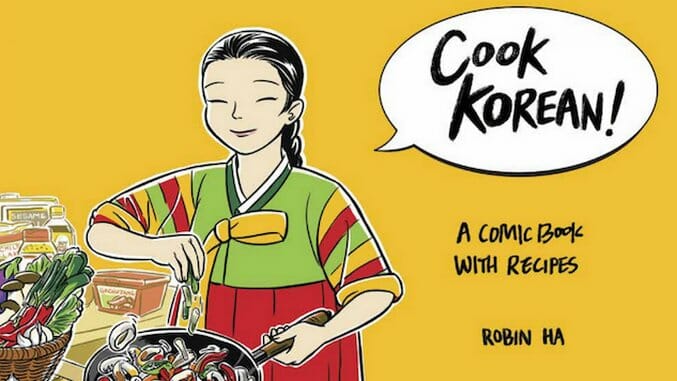

When Comics and Cooking Meet: Robin Ha and Cook Korean!

Illustrations by Robin Ha

When illustrator Robin Ha moved from bustling Seoul, South Korea to Huntsville, Alabama at age 14, the relocation was like losing her senses.

“I was [practically] friendless,” said Ha, now 35 and living in Falls Church, Virginia. “My school didn’t have any English as Second Language classes because I was the only one who couldn’t speak English. I came from Seoul with millions of people and, to me, Huntsville was just fields. One of the hardest things was that in Seoul, I just could run down the street and buy manwha (comics). But it was impossible to find Korean comics there.” Forced to sink or swim with a new language, she picked up English in six months but spent much of her time doodling and slowly befriending the few schoolmates who were enthusiasts of Japanese manga comics in the mid-1990s.

Once isolated as a teen in Alabama, Ha began cooking for her friends as a young adult — many of them, like her, art-school alums and creatives who were strapped for time and cash. And now, more than 20 years after Ha’s emigration and a career in textile and graphic design, the comic book has become her medium and a way to interpret Korean cooking to American audiences.

For her new book Cook Korean! (Ten Speed Press, $19.99), Ha developed and and illustrated about 70 recipes from the Korean peninsula. They range from the iconic Napa cabbage or paechu kimchi to less familiar dishes: chayote pickles, porridges of pumpkin or sweet red beans, and a soybean-sprout soup that’s a common morning meal. It’s a longer and more fully realized vision of Ha’s Banchan in 2 Plates tumblr, where she’s illustrated favorite recipes from Korean chive salad to the Caribbean-inflected coconut-curry tilapia.

Ha’s comic is an accessible entry into Korean cuisine, which had until recently lagged in popularity behind restaurant Japanese and Chinese fare. But now, kimchi is heralded by food literati as a celebrated topping during the continuing burger boom. Lettuce wraps take a page from Korean ssam wraps — grilled meats often cradled in perilla leaves that, if we use winespeak, have notes of mint and anise. And chefs of Korean descent such as Momofuku’s David Chang and Roy Choi have been bringing Korean-inspired spicy flavors to their restaurants and food trucks.

Cook Korean! — which is described as a comic book with recipes — is Ha’s effort to introduce her brand of Korean food as a contemporary convenience food. Of course, convenience is relative. The kimchi isn’t buried and fermented for months in earthenware containers, as of old, or bought in the store like many Koreans do. Ha makes many varieties of the legendary fermented fruit or vegetable dish at home in quickie versions that can be prepared and consumed in as little as a day.

“Korean cooking is really not fussy,” she said. “I can’t think of a time I’ve used an oven. If you have a big pan, a cutting board and the ingredients, all you need is fire or a stove, and it doesn’t take that much time. I think it’s the perfect food for any modern-era citizen, whether you are Korean or not. People have this weird idea about Korean food, that it’s very complex to make.”

That misconception may partly stem from the food’s distinct flavor profile. This fare is not for the milquetoast palate. Even with regional variety, it has a penchant for the peppery and the pungent; a fondness for offal; and its own seafood-and barbecue-rich take on surf and turf.

“It’s very bold. Koreans are good at preserving foods, we’re surrounded by sea and mountains, and we didn’t have enough meat or grain go around. So Korean people have found a way to use every part of the animal, the wheat growing on the side of the road, and things that other people won’t eat. And while people think our food is just about those meat dishes [in Korean barbecue], you can get a full-sized dinner of vegetable dishes in the array of banchan that defy the concept of the side dish as a mere accessory to the entrée.”