Boss Rush: The Binding of Isaac’s Mom Is Just the Start of Your Torment

Subscriber Exclusive

Frequently, at the end of a videogame level, there’s a big dude who really wants to kill you. Boss Rush is a column about the most memorable examples of these, whether they challenged us with tough-as-nails attack patterns, introduced visually unforgettable sequences, or because they delivered monologues that left a mark. Sometimes, we’ll even discuss more abstract examples, like a rhetorical throwdown or a tricky final puzzle or all those damn guitar solos in “Green Grass and High Tides.”

Videogame bosses have a way of starting out as imposing, and then slowly transforming into something more trivial. Nowhere is this more true than in the roguelike genre, where the introduction of a new boss fight to the player is typically intended as a difficulty spike. The player either adapts and rises to the occasion, or they fail … and failure is so often the point. Each of the many difficulty spikes in any given roguelike is likely meant to generate its own wave of death/failure, before the player’s steady progression, be it in terms of skill or incremental upgrades, gets them past this hurdle and on to the next one. The boss fight that first represented such a problem then becomes increasingly mundane, a road apple on the path to conquest. But The Binding of Isaac’s Mom is an exception, not because the fight itself remains a challenge, but because Mom’s implacable status as a “final boss” is woven through the game’s subsequent evolution. A decade of expansions later, the lore and complexity of The Binding of Isaac has grown exponentially, but the shadow of Mom still hangs over every moment.

Simply put, a player firing up The Binding of Isaac for the first time really has no idea of the journey ahead of them. And we should note, when writing “The Binding of Isaac” we’re referring to the 2014 remake of the game, whose official title is The Binding of Isaac: Rebirth. This was the expanded and improved rendition of the originally published Binding of Isaac, which began its life as a Flash-based 2011 roguelike from Super Meat Boy designer Edmund McMillen. Rebirth proved massively popular, with the game and its subsequent expansions Afterbirth (2015) and Repentance (2021) selling more than 5 million copies to date. It is considered one of the foundational texts of modern roguelikes, as a genre–anyone who likes this style of game will be familiar with it. Perhaps ironically, given the name of this column, the game even contains a segment titled the “Boss Rush,” in which the player fights various bosses in a sort of lightning round.

Of course, the reason the game can have a “boss rush” segment is that it has so very many bosses in the first place–more than 100 of them, in fact, in the current incarnation of the game after Repentance was added in 2021. But none of them are so inextricably tied to the mythos as Mom, who when the game first launched way back in 2014 was the original “final boss” of the story. She represents the narrative hurdle to be overcome, established immediately in the opening voiceover, but as The Binding of Isaac is rich in subtext and metaphor, triumphing over Mom simply reveals deeper layers of rot and defilement. Suffice to say, it was never actually going to be that easy.

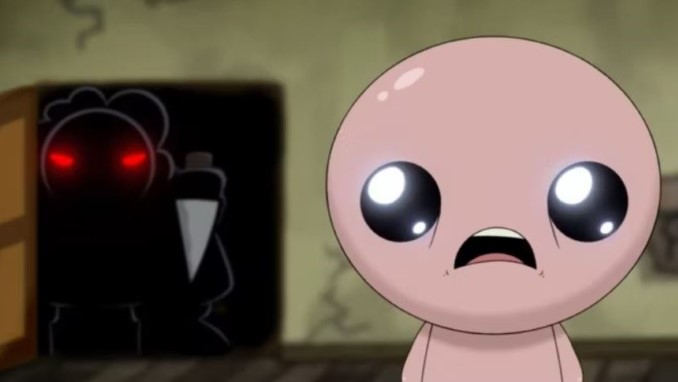

Isaac and Mom in happier times, before she heard her “voice from above” and started trying to kill him.

It was McMillen’s own traumatic upbringing that informs so much of The Binding of Isaac’s aesthetic, particularly in terms of the character of Mom. The game designer grew up in what he described as a household of both intense religious fervor and crippling alcohol and drug addiction. In the game, Isaac’s home is a broken one following the implied divorce of his mother and father, leaving Isaac alone with a mother who gradually begins to lose her grip on reality as she basks in shame, guilt and a steady drone of Christian TV propaganda. When a “voice from above” tells her that Isaac has become tainted by sin and must be sacrificed, she doesn’t hesitate or beg for his absolution. Instead, she picks up a knife. But even as Mom takes on the role of clear-cut antagonist, Isaac–and McMillen–can never really shed the guilt, that nagging feeling that they share some portion of the blame. Isaac’s journey is thus one of castigation.