One of the many ways Wingspan was such a remarkable game when it first appeared was that despite containing a huge number of cards with distinct scoring rules, it still felt fairly balanced. Even now, four-plus years after it first appeared, there are just four cards in the deck of 170 that players have decided are too powerful, although you can still play with them and just accept that whoever gets those cards might have a small advantage. Designer Elizabeth Hargrave, who has a new game out this fall called The Fox Experiment, built a massive spreadsheet to help track and design the scoring rules for each of the bird cards in Wingspan, and that attention to detail is a big part of the game’s staying power.

Forest Shuffle feels like another game that is backed by a meticulous approach, whether in a spreadsheet or built via abacus, where all that work from the designer disappears under the hood. It’s also a card-based game—in fact, the deck of cards is all there is in the box—with a lot of complex scoring rules, including a tremendous amount of interaction across card types, yet it still seems mostly balanced, and once you’ve seen all of the card types after a couple of plays, it reveals itself as a game that’s easy to play, but hard to play well.

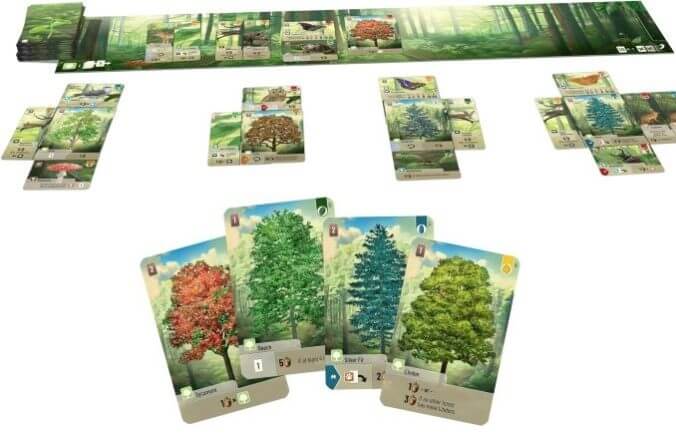

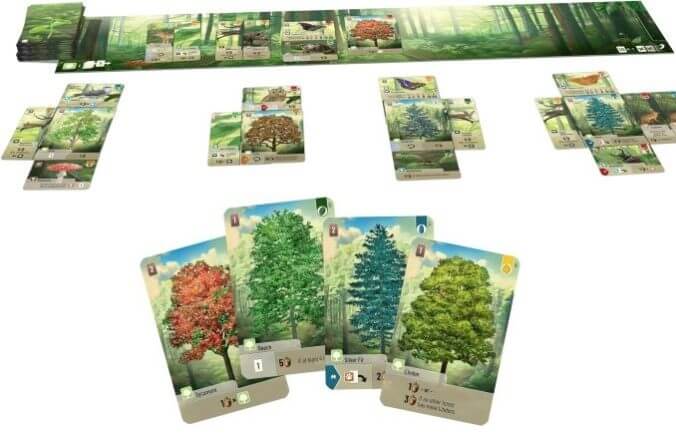

In Forest Shuffle, players will play tree cards to their tableau and then add all the other card types to those trees, placing them above, below, to the left, or to the right of each tree. Most cards have a cost from 1 to 3, and you pay that by discarding other cards from your hand. There are eight tree species, and each scores in a unique way, while some also have additional powers. Horse chestnuts give you points equal to the square of the number of horse chestnuts in your forest. Beech trees are worth 5 points each, but only if you have four or more. Douglas firs are worth five points, but if you ‘pay’ for it with two cards of the matching color/type (pale blue), you get to take an extra turn. And Oaks are worth 10 points if you have all eight tree species in your forest, while they can also give you an extra turn.

All of the other cards contain two images on them, with a line dividing them top from bottom or left from right. When you play one of these cards, you pay the cost and then slide the card halfway under a tree in your tableau. The visible half is what counts for scoring or other in-game powers. There’s a wide variety of card types/colors, scoring, and abilities in the deck, but the most notable part is how much cards’ scoring and/or powers depend on what else is in your tableau. Butterflies and fireflies are worth nothing by themselves, but you get points for the set once you’ve played at least two—in the case of butterflies, two or more different species. A lynx is worth 10 points if you have a roe deer in your forest; otherwise it’s worth zero. Wolves are worth 3 points per deer symbol in your tableau. A beech marten gets you five points for every tree that is “fully occupied,” meaning it has a card in each of the four spots around it. Some cards let you draw more cards, take an extra turn, play another card for free, play as many cards as you want if you pay their costs, or put as many cards as you want from your hand into your “cave” for one point apiece at game-end.

On your turn, you must play a card or draw two cards. You can draw from the deck or take cards from the ‘market,’ which can contain up to 10 cards and includes all of the cards players have used to pay the costs for other cards, as well as one card from the deck every time a tree is played. When the market has 10 or more cards, they’re all discarded. This makes quite a difference in game play, because you might try to force this flushing action to remove a card an opponent needs, or because seeing cards in the market lets you target cards you need for points or for their type/color to trigger a bonus when you play something else.

I do have some questions about how balanced the game is for two players, which is the way I’ve played it the most. There’s good balance in Forest Shuffle, but with just two players, it might be a little too easy for one player to monopolize a card type, or crush one specific strategy, whereas with three or more it’s both harder for one player to get most or all of the cards they need and more likely that two players will try to go after the same thing.

The artwork in Forest Shuffle is really spectacular, although the images take up a good amount of space on the cards, which can make some of the text a little harder to read. (I can’t play this game without my reading glasses.) I also hate the iconography because those symbols are very small, and some of the tree icons differ just by the orientation and color of a tiny cone symbol in the upper right, which isn’t great for color-blind players or folks like me who are old and need visual enhancement. There are also a lot of icons to learn and understand, so you’ll probably refer to the rulebook pretty frequently through your first few plays.

The game ends when three winter cards appear from the deck; you start the game by dividing the deck into thirds, shuffling those winter cards into one pile, then restacking them so the winter cards are all in the bottom third. Game length and time are thus quite variable, as are winning scores, which can range from the mid-100s into the 400s—which is the one other flaw in the game. This is not an easy game to score, not while you’re playing and not at the end. So many cards in Forest Shuffle have variable scoring that you have a fair amount of work to do when the game ends to figure out how many points you have, and that just increases the chances of error. Complex scoring isn’t that unusual in board games, but Forest Shuffle’s scoring is quite involved for a midweight game.

If the scoring part doesn’t scare you off and your eyesight hasn’t started to abandon you as mine has, Forest Shuffle is a very impressive game at heart—a card game with this many moving parts shouldn’t play this smoothly, or be even close to balanced, yet it is. It’s just the second game for the designer who goes by the mononym Kosch, after 2022’s solid, lightweight game Fyfe, and I think both are worth playing. I would recommend Forest Shuffle for gamers, though, not for novices and probably not for younger players under 11 or 12. It’s the sort of game that expects you to know how games work, which I enjoy as someone who’s played a few hundred or so but understand is not the most typical experience.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.