Alex Handy is on the verge of something big, and he’s excited. In fact, it’s his dream.

The founder of The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment — or “The MADE” — based in Oakland, California, Handy and other volunteers devote large portions of their lives and free time to preserving videogame software, hardware and peripherals that run the risk of being lost to time. But there is one project in particular that stands out as a milestone of the organization’s work — a passion project fueled by luck.

The project: to bring the 1986 LucasFilm Games’ Habitat back online in its original form.

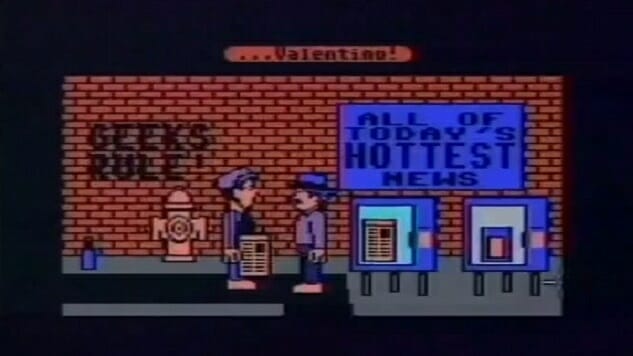

Habitat is ostensibly the first MMO, or “multi-player online virtual environment,” as it was originally called. Developed by Randy Farmer and Chip Morningstar, and released for beta testing in 1986 on the Commodore 64, Habitat was accessible via the Commodore’s Q-Link, an online service the developers ran on Stratus computers, large machines used primarily in banks and hospitals for safety-critical scenarios, via its VOS operating system.

In Habitat, users had avatars—it’s even credited with coining the term. They could chat with other players, interact with objects in the world and even set up laws for the game’s citizenship—features that are commonplace in MMOs today. Habitat was supposedly even developed to support 10,000 players—a feat achieved on a console with only sixty-four kilobytes of memory. Of those sixty-four kilobytes, thirty-two were allocated just to the game’s visuals. Everything else was run with the other thirty-two. For comparison, that’s an entire primitive MMO running on less memory than the average mp3 file.

The game was live for about two years, between 1986 and 1988, after which its beta closed. A smaller version of the game was released to the general public under the name Club Caribe in 1988, also ran on the Q-Link service. LucasArts licensed both Habitat and Club Caribe to Fujitsu in 1989, which later bought its rights completely and have held them until recently, when circumstance brought the long-dormant game into Handy’s life.

While curating an exhibit looking at the history of LucasArts Games at the 2014 Game Developers’ Conference, Handy contacted Farmer and Morningstar, asking for any Habitat assets the MADE might be able to include. To his surprise, the request was met with the game’s entire source code.

“When they did that,” Handy tells Paste, “I kind of felt obligated to do something with it.” He immediately began researching how Habitat might be brought back online, despite being told it was a feat that was likely impossible. Even Farmer and Morningstar explained this point to Handy, though they did eventually jump aboard the project to help.

Handy’s first step was reaching out to Habitat’s license holder, Fujitsu, requesting permission to move forward with bringing its game back to life.

“Generally, when it comes to software preservation projects, there are only two types of responses you get,” Handy explains. “One: you get no response. That means ‘no, go away.’ Two: you get the guy that just starts laughing and says, ‘that is the coolest thing I’ve ever heard of.’” Contacting Fujitsu of America, Handy got the latter response from two lawyers who loved his idea.

“You would think calling a lawyer at Fujitsu would have been the worst thing I could have done in this situation, to alert a lawyer [to our project]” Handy continues. “But in fact, it was the best thing I could have done, because he was so excited about it.”

Because “they thought it was neat,” as Handy puts it, he was able to forgo expensive independent lawyer fees, as his contacts at Fujitsu worked out of their own curiosity and volition. The lawyers began researching the licensing contracts, on their own time, learning what it would take for the MADE to work with the Habitat license. What they found was Fujitsu’s Japanese branch completely owned the rights to the game, and aside from the distribution rights in its home country, the company didn’t really care. The MADE didn’t get the license for Habitat, but rather a hand-wave and a “go ahead.”

“For Fujitsu, this is just an also-ran thing they don’t care about anymore,” Handy says. “Even though they bought the worldwide distribution rights, a Japanese company has absolutely no interest in anything outside of Japan.” Besides, the company hadn’t done anything with Habitat and its later iterations in nearly 10 years, he explains.

The first pieces were falling into place.

As hardware and software becomes outdated, breaks down or becomes lost to time, emulation has become a means to continue running different programs, videogames and more on modern machines. But, as Handy explains, there are little to no emulators available for the Stratus VOS operating system. Thus, bringing back both Habitat and the Q-Link service had to be done on its original hardware. A turning point for the project, where things first felt somewhat possible, came from actually getting into contact with a Stratus employee who thought Handy’s idea “was just the craziest thing he had ever heard of.”

Handy’s research led him to a Stratus file transfer site, and ultimately its administrator, Paul Green, who has been working on the VOS system since 1980.

“I contacted [Green] through email,” Handy says, “and he was like, ‘well you know, I’ve got one of these machines under my desk. I could ship it to you’ … That was sort of the moment where I decided, ‘well gee, I guess we’re really going to have this happen now,’” he continues.

Green not only sent the MADE an intact Stratus computer, but also multiple terminals, dozens of binders of manuals, extra cables and more—all free of charge. He even got the organization into contact with former Stratus employees located in the Bay area that could help get the computer running again.

The next step was getting the 30-year-old computer onto the modern internet.

In an effort to get the Q-Link service back up and running on the VOS system, the MADE organized an all-day “Hackathon”, where volunteers—including Farmer and Morningstar—could come share their interest in the project. This has been the last major work on the project.

Members of the Hackathon were able to get Habitat up and running, but not in its completed state. “By the end of the day,” Handy says, “they got a shim server up so that they were able to connect the client to a Javascript-based server and draw a dude in a room with no head. That’s how far we got.” Progress, none the less.

The biggest hurdle the MADE still faces is an incomplete source code for Q-Link, without which they can’t get the game online, at least in its original state. Once they can get their hands on the missing bits of code, volunteers on the project should be able to begin making headway on getting Habitat online and playable. Handy is currently waiting for a convenient time when everyone can get together for a second Hackathon.

“It’s pushing a rock up a hill, and it’s done in free time by people who are very busy,” Handy says. “We’ll get it [online], I all but guarantee that. I just don’t know how long it’s going to take.”

Once Habitat is up and running, it will be accessible via a Commodore 64 emulator through Q-Link. Or, interestingly, the game will also be available on an actual Commodore 64 console with an ethernet port and access to the internet—though Handy explains that the emulator will be much faster.

From The MADE’s site

From The MADE’s site

When Handy, a reporter for the Software Development Times by day, speaks about the Habitat project, it’s almost as if he can’t stop himself. Answering questions about the Stratus, VOS and the game itself, he immediately jumps into the technical aspect of the project, explaining the minutia of how Farmer and Morningstar developed a game far ahead of its time. He has an almost childlike wonder for extremely complicated technologies.

He likes to stress the fact that videogames are works of art. Much in the same way that film, television and radio classics are preserved as milestones of art, Handy believes videogames should be given the same level of reverence. It’s why he founded the MADE. But rather than strive to preserve a success like Skyrim or emphasize the importance of Doom, Handy looks for the “low hanging fruit” that is both easy to acquire and running the risk of being forgotten forever.

“This is what I wanted [The MADE] to be able to do,” Handy says. “I wanted to be able to bring back dead games, old games, lost content and preserve it. [This] is the fulfillment of the dream for the museum.”

“There is nowhere in the world you can go to preserve an MMO,” he continues. “We are it.” But, according to Handy, this is a double-edged sword. “It’s wonderful to be way out there on the cutting edge, but at the same time we have no idea what we’re doing … we’re learning every day.”

Habitat was immensely influential, but wasn’t quite successful in the commercial market. It hasn’t been ported to smartphones, and its IGN wiki is a mere 56 words long. It could even be argued that the MADE’s preservation project 30 years later is more popular than the game ever was. It’s this lack of industry acclaim that makes Habitat so susceptible to being lost. But Handy hopes that this project in particular will prove to people in the industry that may write off older technologies that there is interest for this type of work, and that older games, even abandoned MMOs, can be rescued and preserved.

Handy isn’t currently sure when Habitat will be playable again. The project has been ongoing for two years now, and it could be one, two or five more years before they finally, fully succeed. He’s confident it will happen, though. And after that, it’s on to the next low hanging fruit.

Blake Hester is a freelance writer based out of Louisville, KY. To read more of his work check out his personal site, blakehester.rocks. He can be contacted at blakehester94[at]gmail.com.