Dandara was a real person. In the 1600s she fought to end slavery in what is today Brazil, alongside her husband, Zumbi dos Palmares. Together with their children they lived in Quilombo dos Palmares, a refugee settlement for escaped and freed Afro-Brazilian slaves, and waged a defensive battle of survival against Dutch invaders and others who wanted to conquer Palmares and subjugate its people. In 1694, after being arrested, she took her own life to avoid being returned to slavery. Dandara was real, and really amazing, and until this game I had never heard of her.

Some of this might be myth. Dandara is a legendary figure in Brazil, with the inspirational legacy of a Greek hero and a real-life relevance magnified by the still-tangible remnants of slavery and colonialism. It’s possible the tales of her deeds have been stretched over the years, but that wouldn’t diminish her power or her significance. That wouldn’t change the fact that she was a real person who fought against real injustice.

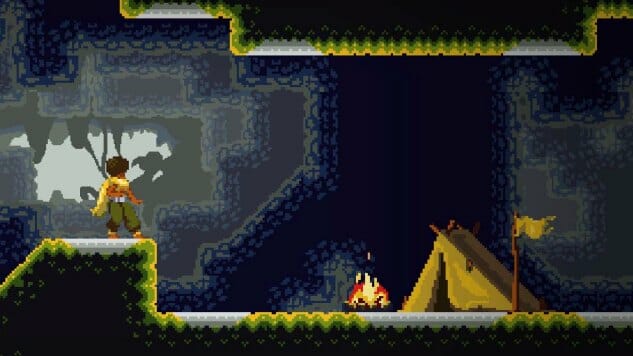

It took a videogame for me to learn about Dandara. Not a Civilization, that reliable redoubt of semi-useful (and semi-factual) historical trivia, but a game called, appropriately enough, Dandara. Made by the Brazilian designers at Long Hat House, Dandara turns the historical figure’s reputation into the launching pad for a science fiction adventure completely divorced from real life. It might be impossible to find the line between history and mythology when it comes to Dandara, but nothing could be easier with Dandara. It’s all mythology here.

Presumably Dandara did not possess super powers that allowed her to warp from one point to another but prevented her from taking a step. Presumably she could not shoot various kinds of projectiles out of her body. When she took her own life near the end of the 17thcentury, she almost definitely didn’t immediately regenerate back at the last tent she slept in. There’s a good chance she didn’t even wear a cool scarf.

I don’t look to videogames for my book learning. We can sometimes learn from them when they want us to, but usually games, including Dandara, are focused primarily on entertainment. The Dandara of Long Hat House’s game bears an even more tenuous relationship to history than the random famous people that are recast as sitcom stock types in any Assassin’s Creed, or those comically distorted world leaders from Civilization. I don’t expect anything different from a game that’s less inspired by the exploits of the real woman it’s based on than by the exploits of popular videogame mascot Samus Aran.

Dandara might owe more to Metroid than to real life, but it still accomplishes something that the many other retro-styled throwback platformers released over the last decade haven’t. It cracks the tiniest possible window into the history and culture of a part of the world that’s largely ignored in American classrooms, illuminating an inspirational real life story that is barely known outside of its own country. If it prompts other players to do even the smallest amount of research (which, obviously, is the exact amount of research I put into that first paragraph above), then it could wind up being a valuable bit of popular history, despite its inherent ahistoricity.

Turning history into a commercial videogame will often be fraught with potential dangers, though. Is increased awareness of an underexposed historical figure worth it if that person’s real life and accomplishments are diminished by squeezing them into a format that’s not right for this kind of story? Dandara opens itself up to charges of trivializing a real life struggle for existence by turning it into a sci-fi cartoon that’s more interested in mechanics than message. But if Long Hat House had taken a more fact-based and historical approach to Dandara’s life, they probably still would’ve seen those same charges, along with accusations of trying to capitalize on colonialism and oppression. It wouldn’t matter that the developers are actually Brazilian and have a closer connection to the source material than designers from other cultures would have—any videogame approach to this story would risk angering or alienating somebody.

This debate basically boils down to this: what’s a better way to tell history through videogames, by making a traditional videogame and potentially inspiring players to research the people and events it’s loosely based on, or by aiming for realism even if that’s not as compatible with making a commercially viable videogame? Dandara spurred me on to (briefly) research Dandara, but I have a lifelong interest in history and the college degree to prove it. How many people who are just looking for a stylish Metroid riff would care enough to research the title character’s namesake? Does Long Hat House have a responsibility to portray history in a more accurate light, or would that be an offensive reduction of the hard life of a woman forced to contend with the evils of slavery and colonialism?

I don’t have any answers. If I did I wouldn’t ask so many questions. Dandara is fascinating not just because it’s a smart take on a classic type of videogame, but because it makes the player consider these questions about the past and our responsibility to remember and preserve those stories. It’s a precisely designed toy box that requires a rigorous unity of thought, action and reaction, and yet it kicks up a host of tricky and imprecise questions about our obligations to those who came before us. Dandara was real; is Dandara’s abstraction of her life a new way of modern mythmaking, or is it a questionable appropriation of her legacy in order to provide a videogame with a semblance of depth? Should it have tried to be the Lincoln of games about 17th century Brazilian anti-slavery warriors, or is it enough to just be Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter?

For now I’ll just keep pushing forward in Dandara, through the robots and monsters and poisonous bubbles, with Dandara’s scarf wafting this way and that as she slices through the air on her way to a videogame’s version of freedom.

Garrett Martin edits Paste

’s comedy and games sections. He’s on Twitter @grmartin.