There’s a push and pull that persists in games, the competing ideas of whether games are a toy or a narrative device. Games have objectives and goals and are meant to be won, and stories are meant to be listened to and experienced. These contrasting expectations are a constant source of conflict in games writing: how to write a narrative around a mechanic, control the flow of information, and tell a story that, despite the unpredictable choices of the player, still has some semblance of linearity. It’s because of this dynamic that often as players, we only play to win.

This commitment to success somewhat makes sense, as games have both micro and macro goals, and usually, the more significant objective of the game is to complete it. To finish the game means to finish the story. But what happens when failure is part of the game—and perhaps an integral part of the game? Are we so focused on “winning” that we lose sight of the many ways to enjoy a narrative experience?

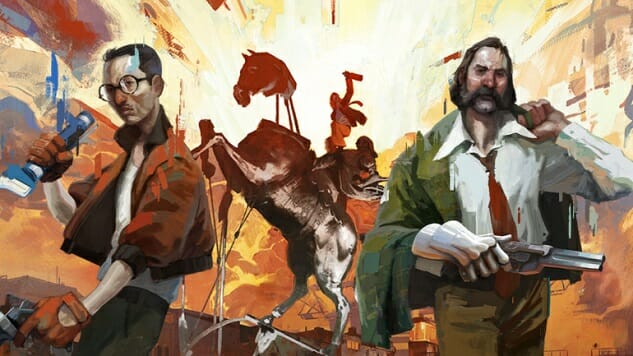

I ponder that as I play Disco Elysium. It’s a gloriously complex isometric RPG, starring a drug-addicted detective with memory issues in a town that has seen better days, that takes its cues from classics like Fallout or Wasteland. Back when those old party-based games were made, it was always a waste to try to play without failing. There were too many variables and few ways to test them all out, save for multiple playthroughs, and trial and error. And part of the fun was seeing how much the game diverged if you had different skill sets and abilities, either through your character build or choosing different companions. But as the years went on, crowdsourced game walkthroughs and other innovations made it easier to plan out how to play. No longer did you have to miss a single thing. Instead, you could supplement the process with a little research, reducing your playtime by hundreds of hours, but also decreasing your hands-on knowledge of the full game.

For me, this change in how we document games fueled a lot of completionist behavior, especially in Fallout 3 and Fallout: New Vegas, where unique weapons and armor (often hidden behind obscure speech checks and quest lines) motivated a lot of obsessive behavior. I spent literal years of my life planning the “perfect” New Vegas run, one that would invest the right S.P.E.C.I.A.L. and skill points with impeccable timing and never encounter any real obstacles. It was an ambitious goal when you consider the hundreds of hours of dialogue and thousands of micro-decisions the game entails. I worked so hard crafting the “best” starting build and abusing the autosave system that I spent more time with my finger hovered the F5 button than I did playing the game.

It’s a shame that I did because the possibility of failure was still written into the story—hundreds of hours of written and spoken dialogue that I never experienced because I was too afraid to make the wrong decision. What might I have learned if I wasn’t so scared of having an option closed off to me if I wasn’t avoiding the acerbic retort of an NPC after a failed speech check? I wonder if I’d opened up myself to that vulnerability, what would certain characters have had to say. How much did I miss when my only goal was to “win” the conversation?

Going into Disco Elysium, I was presented with a selection of three character builds to choose from. As I stared this selection screen down I realized there was no way I could keep playing the same way. With no doubt endless permutations of dialogue and speech checks and quest solutions, filtered through the game’s unique character-building system, there was no way, especially when the game is too young for there to be complete playthroughs available online. So I made the decision not to stress out or even try to “cover all my bases.” With no idea of what’s to come or how to fail (and with the in-game clock ticking away, leaving no room for indecisiveness), it felt better to embrace that my experience would be imperfect. There’s no such thing as a perfect first run. And I’ve ruined games in the past by worrying too much about seeing and doing everything.

So far, that has been the right decision. Disco Elysium is rich with possibility, but it also demands your patience. It immediately establishes both long and short term goals and builds failure into the game. From the first day in Revachol, you can spot several places where mysteries will unfold after certain tools are found or items gained, leaving a lot to look forward to (or catch up on) for later. But there’s also more to be found in the conversations with others if you’re willing to take risks. For my playthrough, I chose the Psyche-heavy build, meaning my character has an aptitude for psychic powers but with the bonus of erratic social interactions. Leaning into that, I haven’t even bothered to maintain civility, saying anything I find amusing, and the reward has been responses I hadn’t expected, sometimes to my advantage.

Other times, to avoid an action or branch of dialogue is to halt the game altogether. You may not understand what an obstacle requires until you’ve already given it a go. Some paths only open once you’ve had less luck with another. Between that and the game’s forgiving speech check system (which lets you re-attempt certain actions or dialogue options once you’ve accumulated the necessary points), it doesn’t feel as though there’s a penalty for trying. That’s important in a game with so many decisions to make and possibilities to explore.

In the end, stressing out about every last detail distracts from the tremendous depth built into the world of Disco Elysium, and I’m ready to stop over-preparing and otherwise manifesting my anxiety in videogames. If anything, it will make additional playthroughs, customized by the game’s peculiar set of character skills, an appealing possibility. I look forward to all the secrets that will soon unravel about Disco Elysium. But even better, I’m feeling comfortable with the mystery.

Holly Green is the assistant editor of Paste Games and a reporter and semiprofessional photographer. She is also the author of Fry Scores: An Unofficial Guide To Video Game Grub. You can find her work at Gamasutra, Polygon, Unwinnable, and other videogame news publications.