I got my PlayStation3 in 2013, near the end of its life cycle, and one of the first games I bought and beat was Far Cry 3, which turned 10 last week. For me, despite finding parallels with LucasArts’ Mercenaries series and, especially, its sister series Assassin’s Creed, it was an eye-opening experience. I was impressed by the absurdity of setting fire to a giant cannabis crop while a Skrillex remix of a dancehall song played. I was annoyed, bemused, maybe disgusted by protagonist Jason Brody—a white American adventure tourist that escapes capture by human trafficking pirates to join up with, and then lead, an extant revolutionary cell (with the help of the CIA). It’s kind of a strange game, representing a nexus, if not a flash point. It’s not a visionary genre-defining experience, but is part of a continuum, an expression of trends that would iterate further; it’s a shooter with strategy, a bit of a first-person RPG, with stealth bonuses and multiple ways to complete missions, but I’ve never heard it called an immersive sim.

It’s a marker of western arrogance and American success produced by a French-Canadian company that took an innovative shooting franchise and used it to push the contemporary omni-genre. It becomes difficult to say to what extent these games are influential and to what extent they’re merely signposts and water level markers, but as an influence on and inspiration to the genre, Far Cry 3 still looms large—and definitely for the worse.

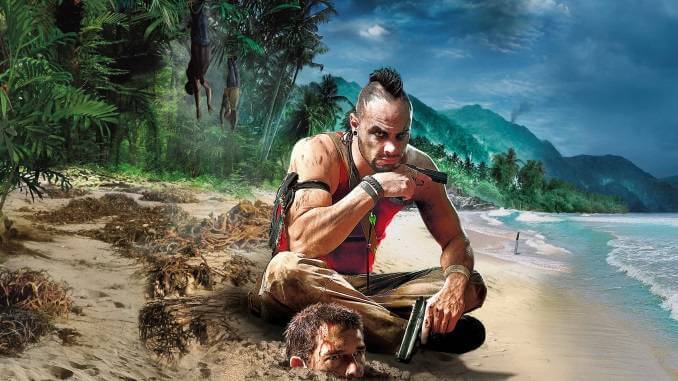

Its creators and fans defended it as a tricky satire that asks tough questions, but is the game’s framing thoughtful enough to be either deceptive or perceptive? It can’t help but subvert itself, but if its interest is in satire and subversion, it’s not smart, clever, or outlandish enough. It’s an overt white savior narrative that your character nearly literally parachutes into. You gain special abilities through a skill tree which is represented through the indigenous tattooing practices of a make-believe tribe. In the end, after your conquest of outposts and radio towers and the mowing down of your fellow white men and the (weirdly beloved by the gaming community) psychopath Vass, you make a choice about whose path to final victory you take. The female leader of the local rebel group—a seemingly close ally—drugs Jason and forces him to choose between her and saving his friends, tricking him into putting a knife to his girlfriend’s neck. If you choose the rebels, Jason conceives a child with the rebel leader and then she kills him. Either way the locals are ultimately villains.

Far Cry 3 is at once exemplary of the videogame power fantasy, featuring a generic white guy saving brown people (at least in this game you’re mostly not tasked with murdering the locals) and of the series’ fascination-cum-obsession with apolitically representing the political. It solidified Far Cry as a series about dropping into spaces around the planet, invoking real historical material, political, and social forces, extrapolating with a low level of sophistication, and creating what the Mercenaries games called a “playground of destruction,” and which I’ve taken to calling a mayhem simulation.

The apolitical political violence simulation also has a long history. Perhaps it even precedes the jingoistic military shooters that began in WWII-era settings and gradually moved into the near future, like Call of Duty and Battlefield (which recently went back to WWI before returning to WWII before a near-future apocalypse). Far Cry sister franchise Ghost Recon recently dealt with a zombie plague, but between the time of Far Cry 3 and Far Cry 4 (which was critiqued for its callous adaptation of Nepal), they set a game in a version of Bolivia where it was a failed state conquered by Mexican cartels. After dabbling in military adventurist tourism, the Far Cry franchise set a game in the United States, dabbling in critiques of far-right religious and militia culture without saying much of note, leading to a post-nuclear spinoff, before stepping far away from contemporary domestic or global politics with a prehistoric game. The most recent release, last year’s Far Cry 6, is set in an imitation of Cuba. And perhaps Far Cry’s closest kin outside of its parent company is Just Cause, where instead of a tourist (as in Far Cry 3 and 4), you play as a spy helping topple corrupt, often corporate-aligned regimes. This is all to say that adapting real conflicts or imaging new conflicts in imprecisely or inaccurately contrived approximations of real places is Far Cry’s bread and butter, and also it has some of the most spectacularly disturbing examples, it isn’t alone.

Far Cry 3 is a crucial point on the gameplay continuum between the more open-ended problem solving gameplay of the PS2-era Grand Theft Auto games (those rereleased as a trilogy recently in addition to their PSP prequels) and the semi-cinematic gameplay of the long post-GTA IV era, encompassing GTA V and the Red Dead Redemption games, where choices are made before missions, but the process of completing objectives requires very specific instructions with lots of innocuous-seeming fail-state conditions.

In the opening to the mini chapter on the game in her 2018 book Gaming Masculinity: Trolls, Fake Geeks, and the Gendered Battle for Online Culture, Megan Condis quotes Far Cry 3 lead writer Jeffrey Yohalem, who said Far Cry 3 was a “meta-commentary on videogames… videogames as a whole, and what we’ve turned a blind eye to in videogames.” As Condis elucidates through quotes from contemporary reviews and commentaries on the game, it comes across cynically, but not as satire, not even pretension. Just “another one of those.”

“One of those” could mean problematic faves like Far Cry 3 and GTA V that don’t push the artforms boundaries in aesthetic or narrative ways so much as highlight how hardware advancement improves the simulation. Or “one of those” could refer to the glut of open-world games—the ubiquitous collect-a-thons where you gradually uncover a map, and do repetitive missions in a space that’s somewhere between well-crafted curation and empty sandbox. Ubisoft makes it in four or five flavors now—historical epics-meet-ancient-alien sci-fi (Assassin’s Creed), first person adventure tourism shooter (Far Cry), third-person tactical shooter (Ghost Recon), and near-future semi-cyberpunk (Watchdogs). It’s the increasingly safe, increasingly rent-seeking omni-genre—the do-everything, feel-nothing game. Far Cry 3, with its white savior thrill-seeking protagonist; its vaguely ethnic, sociopathic villain icon; its vague references to the complicity of colonialism and the western world in creating this lawless space that quickly gets discarded to villainize your rebel allies; and its unrealized aspirations of deeper commentary on the genre, is exemplary of the design philosophy, maybe even one of its high points. It’s one of the more influential games of the last decade, despite its deep flaws, and honestly, that’s a shame.

Kevin Fox, Jr. is a freelance writer with an MA in history, who loves videogames, film, TV, and sports, and dreams of liberation. He can be found on Twitter @kevinfoxjr.