Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest is the scent of a Blockbuster plastic clamshell. Those sharp plastic notes that combined with the faded but trapped scents of too many strangers’ homes—a little beef stew, some dog, a rethinking-her-whole-life soccer mom’s boosted-from-a-Macy’s-by-accident-or-maybe-just-to-feel-something’s tester of Clinique Calyx that leaked in her handbag when she was in a rush to drop the rental off because her kid had left it half under the couch with the game not even in the case before he bolted for school. The accumulated scent of “den” from a time before man caves, or your own television in your own room. If Mystic Quest could have a smell, it would smell like a ‘90s suburban adolescence and all that weirdness and banality wrapped up in one.

Mystic Quest was reviewed pretty okay at the time, but despite that I remember classmates trying to joke on me for liking the game. And I guess history has forgotten that GamePro gave it a 4 out of 5, preferring to remember the position of kids who never grew out of Mortal Kombat fatalities being the best videogames could offer. Mystic Quest carried a reputation into the 21st century of being too simple, too short, and graphically ugly. And since videogames have an institutional memory problem, it’s a good time to revisit this invigorating classic.

In the early 1990s, Square decided they had a problem: shitty American kids weren’t buying enough JRPGs from them. Sure, they had some success with Final Fantasy, and the toned-down for America “Final Fantasy II” (which we now correctly know as Final Fantasy IV), but the market just wasn’t reaching the critical mass Square needed (and wouldn’t achieve until Final Fantasy VII blew the doors off everything). Kids were too busy with The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past and Bill Laimbeer’s Combat Basketball, and then there were all the weirdos who couldn’t get enough True Golf Classics: Waialae Country Club. American kids loved videogames, but they weren’t loving Squaresoft’s JRPGs enough.

Clearly this was because they were too difficult, too complicated, and fussily self-involved.

The original Final Fantasy wasn’t a simple, nice game like Dragon Warrior (I refuse to budge on this one) that let you keep half your gold and your progress when you died (though fuck the magidrakees, for real). It was a game that let you get paralyzed and obliterated by a five-pack of Sorcerers because you always lost the initiative roll. Squaresoft was making JRPGs from the “Fuck You, This Is Wizardry” school. Which admittedly, is not everyone’s cup of tea. While Final Fantasy IV was made gentler for US audiences, it wasn’t enough, and Square’s executives decided that they had to make a game that put American needs first, and that what America Needed was a JRPG so profoundly truncated, so simple a child could demolish it. America needed the Fisher Price of JRPGs.

They needed Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest. Which, in Japan, would be known as Final Fantasy USA: Mystic Quest, despite being made by Square’s development team in Japan.

It had to be simple to understand, with a world that the player couldn’t get lost in, that wasn’t so threatening, and didn’t one-shot an entire party. In fact, why have a real party at all?

Mystic Quest strips the Final Fantasy core down even further, jettisoning the need to buy equipment and spells, or choose a party composition. Even the dreaded random encounter tables are replaced by enemies you can see and plan ahead for. It takes the bricks out of the backpack for new players. Rather than the maximalist Final Fantasy we’re used to, this is the reduction of Final Fantasy to its Joseph Campbell essentials.

As JRPGs go, its story is as stock as any other JRPG made between 1983 and 2021. The world is going to shit and a random old sagacious guy forces a quest on you, because clearly you are the knight of the prophecy (okay, Qui-Gon). You and the friends you make along the way are the chosen heroes who will get the keys to unlock the four doors of a mystical tower and save the world from chaos.

Mystic Quest being a riff on the Final Fantasy franchise means that you’ll go from elementally-themed town to elementally-themed town (specifically, Foresta, Aquaria, Fireburg, and Windia) trying to recover each elementally-themed crystal from the monster that stole it. What’s new in Mystic Quest is the addition of adventure game elements, like using bombs to blow open blocked passages, or a claw weapon that allows Benjamin to climb specific cliff faces. Instead of a party of four, you only get one guest companion at a time. But there are friends who will join your quest from each location, each specifically suited to the task at hand. From the ecologically-minded woodcutter’s daughter Kaeli (whose name in the Japanese localization is Karen, just sit with that one for a moment) and her huge axes, and Phoebe the explosive-minded favorite granddaughter of Aquaria, to, of course, the roguish treasure hunter Tristam. Mystic Quest brings together a small but endearing crew to accompany the player-protagonist who has been given just enough personality. It’s this crew that you’ll roulette in and out of the party, as Benjamin (or PENISBRF, MR. TOES, BUTTFREN, or whatever hilarious 8 character combination your 10-year-old brain decided to name him) adventures his way to fight the Dark King in Doom Castle.

There’s no world map to “wander.” Instead, you’ll move between points of interest on a track, from towns to forests to caves and dungeons. There’s no chance to get lost. It’s almost impossible to forget what to do next. And unlike Final Fantasy, there’s zero chance you’ll get slaughtered by a pack of Sahagin going from the second town to the third town. It’s refreshing to not have to worry about all that. Stripping Final Fantasy down to its barest moments allows for a game that’s charming and delightful. There are no anime convolutions of melodrama, but it’s also not as sterile and published-TSR-adventure-module-feeling as the original Final Fantasy.

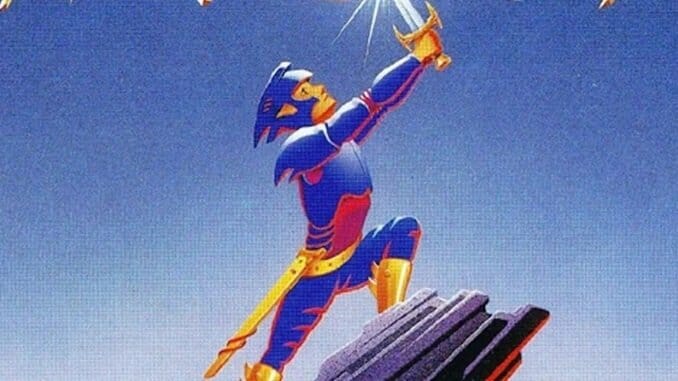

Straightforward and breezy, Mystic Quest isn’t going to win awards for narrative complexity or systems depth. But it’s not a mere skeleton of a JRPG either. Mystic Quest is a game that allows for some warm and funny character writing between Benjamin, his friends, and the various townspeople who all need help in some way or another, along with the occasionally tense but still low-key boss fight. You won’t be spending hours scrolling through GameFaqs forums trying to find the Optimal Build for Your Dudes. Benjamin & Co. get levels, become stronger, and get gear handed out to them as you progress through the story. Mystic Quest has just enough in it to let you guide the journey, but not so much you’ll ever stray off the main road. And where the graphics and systems may be simple to some, the manual art by Katsuya Terada and soundtrack composed by Ryuji Sasai and Yasuhiro Kawakami are phenomenal. In a way, Mystic Quest feels a lot like a fully-formed RPG Maker pack-in game. Which isn’t a dig at all—RPG Maker (even at its most straightforward) is extremely cool. Mystic Quest makes apparent how the JRPG genre fits its pieces together, paces itself, and constructs a world and the characters who populate it.

Also, it’s really short. Like, really short.

You can beat the game in a single weekend. Really, a day if you wanted to (but you can also take your time, when you’re not off-handedly reviewing it, and there’s no Blockbuster you need to return it to on a Monday morning before school). In an era where even action games are becoming 40 to 60 hour affairs, it’s nice to play something that’s solid, simple, and 8 to 14 hours long. It’s nice to play a “big game” that isn’t completely stuck on a Game Hour per Dollar valuation. But do you really need to play Mystic Quest? In a world of bloat and excess, a game that defines itself by its lack of options and complications is a break for the overburdened mind, and the episodic shonen anime way Mystic Quest plays out means it’s easy to pick up for an hour, then put back down. It’s a game that’s confident enough to be small and simple. Even if its origin is mired in marketing nonsense, Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest remains a fantastic diversion from the core franchise and a good reminder of what games could be.

Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest was developed by and published by Square. It’s available for the SNES. I mean, it came out in 1993. C’mon.

Dia Lacina is a queer indigenous writer and photographer. She tweets too much at @dialacina.