A witch who can transform into a scythe asks to meet me at a local church. They are grieving their grandmother who recently passed and trying to make sense of our strange friendship at the same time. You see, I wield their scythe form when we dungeon-delve or “Dunj” together. We are both considering our mortality and that of our loved ones–often and how to process our grief. I spend some time talking to them about how they are coping and they surprise me by turning the question back on me. “Have you lost someone?” I feel my mind do a double-take: no, I don’t think I—wait, of course I have. Recently in fact. I won’t say who I lost other than to say that they were someone whose loss caused a disorienting tectonic shift for my inner child. Their loss signaled the cordoning off of a younger era of my life and solidified the point of no return to it.

Yet being able to share this vulnerability with one of my favorite characters, Rowan, in Kitfox Games’ adventure-dating sim Boyfriend Dungeon, allowed me to come to terms with some of the grief I’d been holding for half a year. As the meeting with them drew to a close we bonded by meditating together and acknowledging that we could make sense of our mourning through empathy. The reasons for this are well-explored in both games criticism and podcast series like Play Dead, hosted by Gabby DaRienzo of Laundry Bear games, the indie studio behind A Mortician’s Tale. Games have a lot of cathartic potential and offer a safe space to deal with difficult emotions without any judgment.

There are major shortcomings with portrayals of grief in games, however. At the AAA level the shortcoming is one of scale or perhaps intensity, to be more exact. Games like the Hellblade series, The Last of Us series, and God of War (2018) are often dealing with portrayals of epic grief set in worlds or plots that accentuate the nature of the protagonists’ grievances. While there are quiet moments within these narratives which accurately capture the different shapes grief can take, I find for me at least that the epic metaphors hold me at a remove from the text.

This distancing due to allegory happens also in smaller budget games like Gris or Spiritfarer (though the latter is more adept at balancing allegories of grief with mundane expressions of it).

Gris is a beautiful visual representation of grief with its aesthetically pleasing ruins and the protagonist’s quest to overcome her depression to rediscover her singing voice. As I’m both a visual and linguistic person, this representation is one that helped me through a rough patch when I felt disconnected from my creative purpose. But ultimately Gris is a game that some players might find too abstract to empathize with. The trouble with epic metaphors for grief is that they attempt a universal narrative of the emotion and its expressions. Neva, Nomada Studios’ next title, at least focuses on a less vague sense of grief by centering the narrative on two characters and their bond. But I still felt a nagging sense of melodrama to the initial trailer.

Having smaller, lower-stakes grievances can counter this design challenge. It’s understandable why games, especially at the AAA level, feel that they need to maximize the cathartic potential of a grief narrative. AAA games are obsessed with empowerment of the individual as well, so it’s in their (supposed) best interests marketing-wise to make their players feel like they’re triumphed over their grief. But the thing about grief is that it’s pervasive, and although we’ve identified those so-called five stages of it, it’s not a linear progression nor an automatic process. While you might be able to take action against your grief as an entity in epic narratives, there’s no guarantee that you will suddenly vanquish your real-world grief in the same manner. In other words, you can’t press X to will your sadness or bereavement away.

Dating sims like Boyfriend Dungeon and romance or friendship paths in games allow us more mundane moments of grief, no matter how speculative or epic the overarching plot of the game is. Many people have spoken about how Bioware characters like Thane or Cullen have helped them come to terms with grief related to illness or addiction. Delving further back in time, games like Persona 3 showed us that sometimes, more than earth- and reality-shattering supernatural forces, the most difficult challenge is coming to grips with our mortality.

Tales of Kenzera: Zau, for instance, is an Afrofuturistic platformer inspired by African folklore about a boy trying to reckon with the loss of his father to a sudden illness. There’s a parallel story where Zuberi, the mourning boy, engages with a story written by his father to make sense of his mortality. This story is given to Zuberi by his mother, who appears pregnant with a second child. In this parallel story we play as the shaman Zau, an obvious standin for Zuberi, to help him reconcile with his grief and find meaning in his father’s passing. Although there are elements of things that usually abstract the grieving process present in Zau, the game avoids pitfalls by centering loss as well as finding and making peace with the past. Every level, mechanic, and enemy is considered one more thoughtful brush stroke in its nuanced illustration of grief.

You are a shaman who makes a bargain with Kalunga, god of death, to retrieve his father’s soul and have the power to put troubled spirits to rest. This power is dual, based on the sun and moon and how one must balance the different aspects of oneself to see their path ahead clearly. Levels mirror Zau’s mental state as he grapples with his wounded pride and sadness, with alternating lows and highs occurring parallel to his turbulent emotions. An extended mission in Act One sees Zau seeking the forgiveness of a girl who he frightens in his intensity to barrel through his quest, seeking not just his father but glory. The game is adept at communicating grief both through earnest dialogue writing and a game system aligned closely with its themes. But what I love the most about it is that it doesn’t shy away from portraying grief as a rhizomatic, multifaceted experience.

More often I have encountered this plurality of grief expressed in smaller game projects or independent ones (think To the Moon or That Dragon, Cancer). There are some AAA games that have stuck with me over the years, like Fumito Ueda’s oeuvre, which covers loneliness and burdens shared between humanoid and more than human entities. Klonoa: Door to Phantomile struck the same chord with me as well.

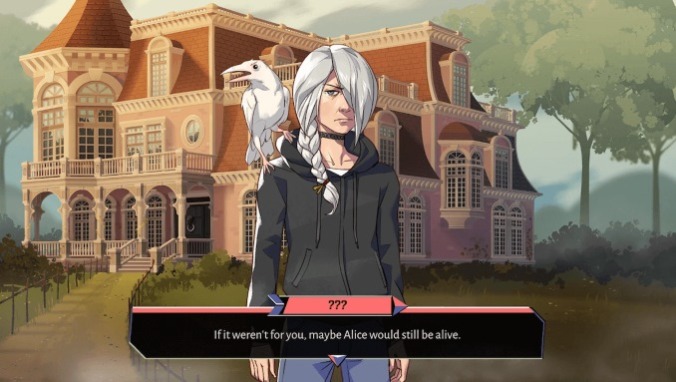

To get back to the realization that made me contemplate all the above, Boyfriend Dungeon is a dating sim that is not just about romance or sex, but vulnerability experienced during times of grief. There’s an interwoven theme of connection helping a community work through their mental health issues. Seven the lasersaber struggles with chronic depression and the main antagonist is driven by extreme loneliness. The onus for healing is not centered solely on your protagonist either, though they are a key agent as a wielder of weapon people. Practically every character in the plot has their individual fears and like the dungeons of the Persona series, one of the main inspirations for Kitfox Games’ title, even the monsters are representations of various submerged fears in the protagonist’s psyche.

The games that deal with grief best are the ones that acknowledge that grief is not singular, even if it can be a force of isolation. And as we continue to become more aware of our interconnection throughout our current pandemic and global crises of climate change and genocide, I believe we will continue to see many more games stressing communal grief. The grief expressed will sometimes be systemic and overarching, like Citizen Sleeper, Eliza or NORCO. Other times the grief will be more intimate, mundane and intergenerational, as with titles like Mutazione, If Found, Venba, Dordogne and A Space for the Unbound. There’s an emphasis on communal grief in recent wholesome games as well, with Cozy Grove and the upcoming After Love EP. Grief is multifaceted, diffuse and viral. There isn’t a singular story of grief and we need the voices of a collective to reconcile with the effects of this deep and layered emotional state.

Phoenix Simms is an Atlantic Canadian writer. She runs the column “Interlinked” at Unwinnable, is the co-editor of The Imaginary Engine Review (TIER) and an indie game narrative designer. You can find her portfolio here. Her stream-of-consciousness is mostly present in bluer skies these days.