Despite its flaws, Until Dawn worked for me. For a time, Supermassive Games was an exciting new voice in the realm of videogame horror, a section of gaming I have always considered myself a fan of but engage with very little as new releases are announced. Their style is corny, sure, and the stunt casting is more than a little reminiscent of mid ‘00s horror movies that marketed themselves on watching Paris Hilton die (maybe intentionally so!), but the construction of the game—the moment to moment—remains exciting despite cliches, shorthands, or troublesome writing.

Nothing Supermassive has done since has particularly sparked anything in me. This year, I went into The Quarry with an open mind and had a good time, in part because I played it with a group of friends, but as time passes since playing the game the less I think about it and anything outside of its most bombastic moments. Slowly, I realized a lot of this has to do with the game’s exploration segments, in between the scripted, QTE-laden encounters. The brunt of a horror game is usually in these sections; there’s the atmospheric puzzle-solving of Amnesia: The Dark Descent, the tense stealth of Alien: Isolation, and the point-and-click nature of Clock Tower. Slowly, throughout these games, you learn the rotations of the enemies stalking you, the areas in which you can travel safely and release some of the tension that’s been building throughout. In Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, moments of danger are very carefully delineated—half of the game finds you searching the town for clues, responding to your phone’s radio signal, and answering telephone calls. This is all strictly atmospheric. There are no enemies during these sections. It’s not until you stumble into a “Nightmare” zone that you are stalked relentlessly by monsters, only able to run through an obstacle course until you find your way out.

For exploration to feel resonant, the experience has to, in some ways, be bespoke, purposeful. A game can still be chilling even without the threat of imminent violence. But for horror to work, there must be an element of chaos, unpredictability, or dread. In The Quarry’s interstitial moments, you follow the character you’re controlling in an over-the-shoulder view, whipping the camera around them any way you like, besieged by motion blur and darkness. There are environments—like the cabin at sunset—where the staging feels quite intentional, creating slivers of safe, glowing light on the hardwood floor against contrasting silky blackness. Unfortunately, in these instances, I often failed to consider them; it’s easy to miss this kind of ambience when I have full control over how I’m seeing it, which affords me a sense of safety and power. Until Dawn is careful with its angles, often placing the characters in the middle of the screen with a considerable draw distance, allowing the camera to creep behind them slowly, pan up, zoom in or out. The direction plays on both the agoraphobic fear of a wide, snowy forest as well as the suffocating oppression of a narrow tunnel. Amid the intricacies of the camerawork—often moving while slightly out of step with your inputs—the player is expected to explore the mountain knowing they may be walking into a chase sequence. This is a marked improvement over Shattered Memories’ idea of exploration versus powerlessness, where the lines are further blurred and paranoia can ratchet up quite quickly.

Many would point to the first three Silent Hill entries as touchstones for horror game direction, and they’re right to do so. But when I think of the camera specifically and the power it holds in these games, I always think of Capcom’s Haunting Ground, their 2005 spiritual successor to Clock Tower. Haunting Ground boldly champions its own influences. The psychosexual, stylized work of giallo filmmakers like Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci were clear inspirations for the game’s pulpy, exploitative story, but from these movies Capcom also took a pervasive sense of creeping dread.

Haunting Ground comes with its own set of warnings, even ones atypical for horror games; the horror in the game is often sexual in nature. Fiona is hunted for her body, and the desire to possess the unique element she houses within manifests as sexual desire and feminine jealousy in her many enemies. Her body is quite literally a commodity, and her role in the story is that of frightful game, chased through hallways and slipping past assailants. The camera occasionally ogles Fiona, yes, and she even starts the game wandering about in a thin white sheet. There are times when the camera is just beyond a window, remaining perfectly still as you control Fiona solely. This staging draws the viewer into the madness, making them an active voyeur in Fiona’s suffering, while also implying the constructedness of Fiona’s imprisonment in the castle. She is watched and strung along with purpose and intent.

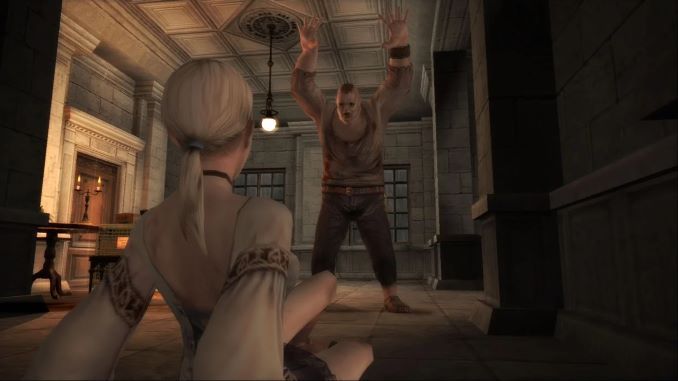

How each room is framed expertly emphasizes Fiona, allowing her chasers to enter the frame from multiple directions. This is one reason why the game’s simple, combatless form of exploration works so well; she can be descended upon at any moment, so you must traipse about and collect tools to proceed knowing there is little you can do before a crazed murderer could burst from stage right. The areas in which the camera obscures—behind pillars, doors, or under couches—are also the places Fiona can hide, not just from the camera but from her assailants. Most of the time this is the only way you can stop them from chasing you.

Like in many giallo films, or even the Universal Monster movies such as The Invisible Man or Dracula that the director stated as an influence on the game, the elaborate setpieces work precisely because they are artificial. It’s something of an obstacle course for Fiona to run around desperately, hoping to find some form of escape or reprieve. Each section of the game finds you mostly contained to a wing or area of the castle, but there’s enough rooms that you may stumble into one as you’re fleeing one of the stalkers. There’s a sort of surreal fear that comes with breaking into some of these rooms, especially as the music dims to slight atmospherics. There’s a dark nursery with a facade of dolls etched into the wall and one rocking in a chair right in the center of the room, a room that contains half of a carousel where you’re only able to see and control Fiona through a mirror, and arcane looking laboratories with strange schematics and androgynous mannequins.

There are boss battles of sorts, but the bulk of Haunting Ground is solely exploration, an aspect the game heavily marketed itself on. It’s “Survival Horror Meets Unique Gameplay Variation,” which the director of marketing referred to as “not your typical survival horror game.” But when boiled to its bare essentials, Haunting Ground is really quite simple in its progression and gameplay. Training your dog, Hewie, to listen to your commands is a rather esoteric (and frustrating) system, sure, but most of what you as a player can do in Haunting Ground is identical to what you can do in Clock Tower. What makes the game so memorable is how these ideas are presented. Without directly stating the gravity of Fiona’s possible violation, we’re able to infer a sickening, perverse threat in the items placed around the environment and how the camera focuses on them. Similarly, the unique differences in each of Fiona’s stalkers—one a brawny giant who wants to rip her apart like a doll, another an unstable maid scornful of Fiona’s fertility—is communicated through the environments they chase her. Where Debilitas, the giant, charges her in several large, foyer-like entrance halls, Daniella slowly pursues her down dark, twisting stairwells and across winding catwalks. The panic imparted by these two is wholly different, thanks in part to the harmony between their natures and the mise en scene. What could happen to Fiona if she’s caught by one of these assailants ultimately does not matter; we just know they are scary as hell.

Haunting Ground is a wholly unpleasant and depowering experience, but one of the most decisive and willful I’ve sat through. Though the game clearly has some cinematic inspiration, it appropriates these elements and applies them in abstract ways, separating it from the literalism of other horror movie influenced games. Regardless of the experience itself, though, I’m consistently impressed by the game’s beautiful environments and thoughtful camerawork, with its sinister, controlled stillness and lascivious eye. Horror games could do well to dive into the lecherous just a bit more; what is horror without a twisted sexual dynamic?

Austin Jones is a writer and perfume enthusiast. His unfiltered thoughts are available for free on Twitter @belfryfire.