Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story Digs Into the Underground Past (and Future) of Games

I can’t imagine hating myself or my free time enough to ever argue about if games can be art or not. Somehow it never stops, though; people have been weighing in on that insufferable debate for decades now, despite it all being such a colossal waste of time. That question was settled 40 years ago by one single guy. Jeff Minter is an artist, and his medium is videogames.

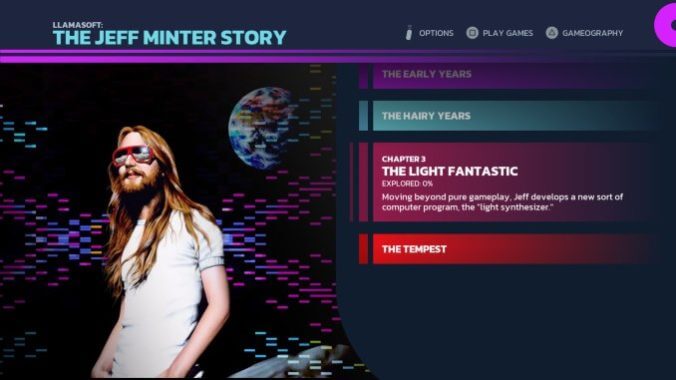

I don’t see how anybody could think otherwise after experiencing Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story. The latest entry in Digital Eclipse’s groundbreaking Gold Master series of playable documentaries collects dozens of Minter’s early games, from his earliest ZX81 rough drafts up to his 1994 masterpiece Tempest 2000, and the hallmarks of a true artist are unmistakable. Throughout his career Minter has continually iterated on similar themes, mechanics, and images, creating a unified body of games whose dreamlike logic and visuals are at odds with their strict difficulty and well-defined mechanics. Minter’s work exists in the contrast between form and function; he’s a visual iconoclast resolutely exploring the most traditional notions of “gameplay” through surreal arcade games that always bear his personal signature.

What I’m saying is his games look like abstract art and play like something you could’ve found in a bowling alley arcade in 1985, and that’s about the most bulletproof approach to game design I can think of. They look like the future and play like the past and feel absolutely like today. A Minter game is always worth playing and almost always good, no matter what year it was made or what hardware it was made for. There’s nobody else like him and nobody else in games who is so clearly and undeniably an artist. And all without being a precious, pretentious twit about it. Good job, Jeff.

What’s a Jeff Minter game like, though? Since 1981 he’s been making increasingly psychedelic and complex arcade-style games with a distinctive sense of humor and frequent references to such animals as sheep, camels, llamas, and giraffes. Games like 1982’s Andes Attack and 1983’s Attack of the Mutant Camels riff on arcade hits Defender and The Empire Strikes Back, respectively, only with Defender’s humans replaced by llamas and the AT-AT walkers of Star Wars turned into giant camels. 1982’s Gridrunner, which wound up being the best-selling computer game of 1983 in the U.S., is a blisteringly fast sci-fi spin on Centipede that ultimately improves on its inspiration. Tempest 2000, probably the best known game of the lot to modern audiences, is a trippy mid ‘90s techno update on Atari’s classic ‘80s tube shooter. Minter’s games largely depend on shooting (or blasting, as Minter calls it) through progressively faster and more chaotic environments full of flashing lights, pulsing colors, and enemy swarms; as hardware has grown more powerful, Minter’s games have become more abstract and psychedelic, as can be seen with his brand new version of Atari’s Akka Arrh (which was released by Atari on March 8 and is not a part of the Llamasoft collection) and 2017’s Polybius (which is also not on Llamasoft).

Just as earlier Gold Series entry The Making of Karateka and its precursor Atari 50 gave us an in-depth look at the background and creation of the games they focused on, Llamasoft is full of videos and archival footage about Minter’s history and how his games were created, marketed, and received by the press and the public. Minter himself is beguiling, a shamanistic figure who indulges his love of computer games, psych and prog rock, and hoofed mammals in semi-seclusion in Wales, and who has been an outspoken proponent of independent game design for most of his career. He began making games at a time before corporations had come to dominate the business, stamping out the kind of personality and individuality his games are known for, and although he has worked for giant companies throughout his career he’s been able to maintain his independent spirit, making and releasing his own games between projects for Atari, Microsoft, and Sony. Although it’s only focused on one designer, Llamasoft has a “you had to be there” vibe similar to Our Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad’s seminal history of the 1980s underground rock scene in America; both capture a thriving period of artistic freedom and innovation right before giant corporations figured out how to exploit, commodify, and depersonalize the scene.