In Pentiment, People Are Like Books, and Books Are Like People

In her essay on vellum, the material made from animal skin that forms the pages of medieval manuscripts, Sarah Kay begins with the following observation: “As skin, it becomes in fantasy a double of the reader’s own skin—for example, as an envelope, or as an opposing face.” Pentiment begins with you returning a manuscript to its blank, animal-skin state, dragging a stone across ink to erase it. Not as simple or trite as “writing your own story,” it’s an act of will that sets you up to make the choices you’ll be presented with throughout the game, choices that will not be marked as true or false. This is a theme that carries through into the rest of the game with incredible consistency, leaking into its art, narrative design, and structure: people are like books, and books are like people.

Pentiment is set in the town of Tassing in Bavaria, just after the turn of the 16th century. You play as master artist Andreas Maler, who as part of his Wanderjahre (wandering years) is working on a commissioned manuscript at Kiersau Abbey, just above the town. He is almost immediately drawn into preexisting tensions between the abbey and the townspeople whose taxes finance it, and then into a murder which he takes responsibility for investigating. This is the first place Pentiment stakes its story-shaping ethos: no matter who you choose to convict, the game moves forward without giving you a “right answer.” (Maybe it goes without saying that you are best served going in knowing as little as possible about Pentiment’s structure, or the specifics of the story.)

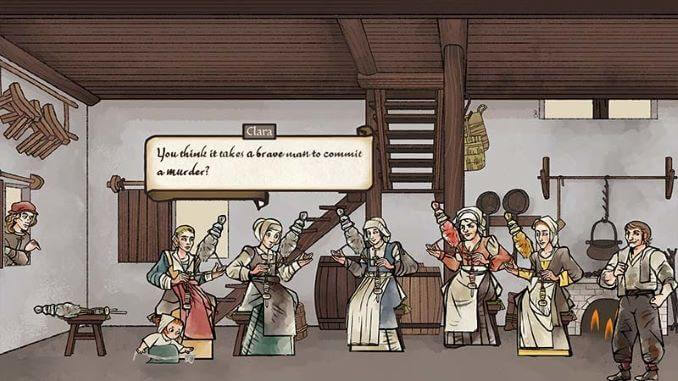

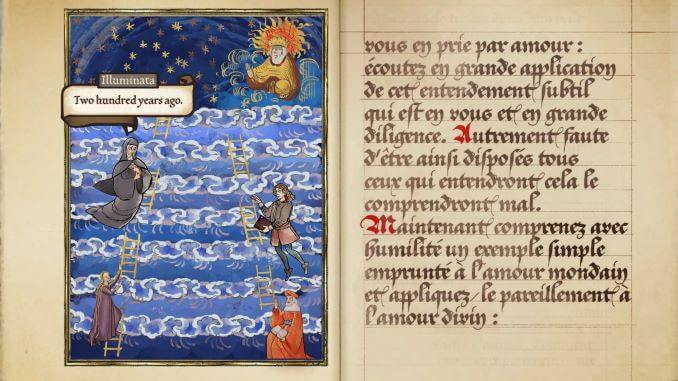

You spend most of your time speaking with others to find information about the murder and the town, conversations that look like they’re out of a book themselves. Individuals speak how they write: Maler’s dialogue comes out in Gothic script, the kind you’d see filling a 14th century illuminated manuscript, while the printmaker lays out his speech in black blocks. The educated use the same script as Maler, those who read a little use a Carolingian cursive, and kids use chicken scratch with lots of errors. This and the illustration style make the characters really feel like they are living in a manuscript, and they also remind us of the different levels of education in a town where almost everyone reads a little. Throughout the game, various characters tell stories from within the pages of a book: Sebhat, an Ethiopian monk stationed in Rome, tells the story of Lazarus out of an Ethiopian Bible, while the sister in charge of the library floats with you through a dialogue between Love and Reason.

All this characterization pays off as time passes and you get to know the townspeople and monks. The growth you see is especially important given that Pentiment is set in one of the most fascinating transitional periods in medieval European history, between the invention of the printing press and its eventual replacement of handwritten manuscripts. When Maler arrives in Tassing, the abbey scriptorium he works for is on the edge of shutting down, the printmaker in town has been perfecting his woodcuts, and the visiting baron has some questions about the newly-circulating ideas of Martin Luther. Invariably the two eras the town is stuck between come out through the many, many books and works of art you encounter, from popular manuscripts like the Golden Legend to contemporaneous herbals and the Swabian Twelve Articles.

Pentiment uses all these texts to ask questions about what the purpose of an artist’s work is. Is it to copy the style of others? Is it to record history exactly as it happened? Or is it to advance an individual style and maybe grasp at the divine? These are all questions that suit a time when a culture of anonymous authorship was giving way, thanks to the printing press and pamphleting, to an industry where an author’s (or artist’s) identity outside the text was more important. They’re also questions that many people you speak to find irrelevant. They’re worried about personal legacy, sure, but they also need to make sure the crops come in.