I Apologize to Anybody Who Expected Me to Do Anything This Year Other Than Play Picross

Games Features picross

I’ve spent all of 2021 staring at squares. Just rows and columns of squares, making up bigger squares within bigger squares, neatly arranged in perfect precision. Sometimes these grids are 5 by 5, or 10 by 10, or 15 by 15, or even bigger, and always with numbers on the margins. I use the numbers to fill in the squares to make pictures so blocky and abstract that they look like Atari 2600 games, not because I want to see those pictures but because I want to unlock the next set of squares, and then the next after that. This is my 2021. This is my life. If you’ve expected anything else from me over the last two weeks, I apologize.

All I’ve done so far this year is play Picross. It’s all I’ve accomplished. If I passed away today it would most likely be because of the amount of sleep I haven’t been getting while playing Picross. My name and dates on my tombstone better be chiseled in as a Picross puzzle.

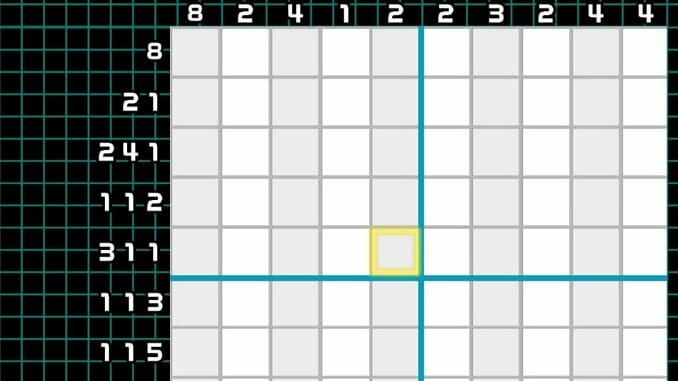

If you aren’t familiar with Picross puzzles, or the generic term “nonogram,” they’re logic puzzles where you have to deduce which squares in a row or column should be filled in based on those numbers listed at the side. Each number tells you how many contiguous squares should be colored in. If there are multiple numbers next to a row or column, those will be separate sequences in the same line, with at least one empty square between them. So if you’re looking at a 10 by 10 grid, and a row or column has the number 7 next to it, that means there are seven consecutive squares that need to be filled in. If it had the numbers 5 and 4 next to it, that means there’d be five consecutive squares to fill in in, and then an empty square before a second run of four consecutive squares. That second example is easy to figure out—in a row with 10 squares and the numbers 5 and 4 next to it, you’d fill in the first five squares, skip the sixth square, and then fill in the final four. It’s a logic problem that you have to tackle line by line, filling in the squares you can tell are occupied; as you shade in more squares in other rows and columns across the grid, solutions will start to fall into place.

This is what a Picross puzzle looks like when it’s born.

As you fill in the correct squares (or, as this 1995 SNES game depicts it, chisel away the correct squares), the puzzle gradually reveals an image.

When you complete the puzzle, the game will usually add the last bit of visual definition to let you know what you’re supposed to be looking at. Sometimes that means color, other times animation. This, apparently, was supposed to be a flame the whole time. Or a very abstract rendition of that “Elmo spurring on the flames of Hell” meme.

Picross isn’t unique in how it can dominate my brain (there’s this game called Tetris, check it out) but something about this particular case feels unique. And no, despite Picross’s rigid devotion to rules and logic, I’m not going to bleat on about how it’s providing the structure and dependability currently missing from the real world. This isn’t the result of the pandemic or our inescapable political turmoil. My Picross obsession says less about current events and more about me and the ubiquity of technology in our daily lives. I can’t escape Picross because it’s pretty much everywhere I go, if I want it to be. And ohhh, how I want it to be!.

During the pandemic I spend my days shuffling between three pieces of furniture. There’s the chair where I do my work, the couch where I sit and drink when I’m not working, and the bed in which I sleep. If you count the phone I am always staring at in bed, all three of them are directly in front of a screen. All of those screens are connected to devices on which a version of Picross is playable. They’re three very different versions, too: on my computer there’s a cheap Picross riff that popped up on a Steam search; on the TV in front of my couch there’s a 1995 Super Nintendo version of Picross available through Nintendo’s online app, in its original Japanese; in my bed there’s an app on my phone with puzzles that, when solved, reveal pictures of characters and images from old Konami games. That last one is the true killer: even when I am trying to do something else—watch TV, eat dinner, wait out a red light during the one hour a week I go for a drive—I’m trying to make a Castlevania turkey leg show up in that damn Konami Picross app.

As far as smartphone obsessions go, Picross seems at least a bit more admirable than Twitter or Instagram. There has to be some kind of cognitive benefit to solving logic problems, right? At least more so than cruising sea shanty TikTok or “liking” the latest dunks on Ben Shapiro. Sometimes I envision it like those terrible mobile game ads that claim to test your “brain age” through a generic match three or word game; when I start a Picross puzzle my brain is at 100, old and foggy, and as I fill in each line that number drops a little bit, until it’s slightly less old and still foggy.

It doesn’t help that I tend to mix my Picross with rum and Diet Coke.

The satisfaction I feel when I complete a Picross puzzle feels about as good as a sip of that cocktail, to be honest. Instead of making my taste buds buzz, though, it immediately hits whatever part of the brain is stimulated by success. Did you hear that, everybody who ever doubted me, everybody who I ever failed? I might have screwed up constantly back then, been just the least dependable and most incompetent oaf ever, but at least I was able to chisel out this poorly rendered penguin in a 25-year-old Japanese videogame. And with another puzzle always waiting after that one, it’s hard to ever put whatever version of Picross I happen to be playing down. Both Picross and that rum and Diet Coke exploit the addictive part of my personality; finishing one is a minor triumph, and it can immediately be followed up with yet another minor triumph, again and again, deep into the night, oh God is that the sun already?

So many triumphs. So many bottles.

If you’ve needed or expected anything from me this year, I am sorry. It’s not me who’s unreliable; it’s the me I become when Picross sics its uncaring hooks deep into my brain. Those squares have a tendency to push everything else aside—everything except the rum. Mix them together and I just get paralyzed. Eventually this will run its course and I’ll be able to confront life without a Picross puzzle in one hand and a glass in the other, but until then, I’m sorry, and please be patient. I’m trying.

It’s the Picross. It’s definitely the Picross.

Senior editor Garrett Martin writes about videogames, comedy, music, travel, theme parks, wrestling, and anything else that gets in his way. He’s on Twitter @grmartin.