The Peace and Fury of the Shoot ‘Em Up

The Shmuptake #1: An Introduction

I can’t stop playing shoot-’em-ups. I’ve had that problem for close to 40 years and I don’t imagine it’ll end anytime soon. I’m not saying I’m good at them—enjoying something and actually being talented at it have no correlation whatsoever—but I have played a lot of them, and continue to play a lot of them, and since part of my job is writing about games it seems like a reasonable decision to write about these games. So let’s do it.

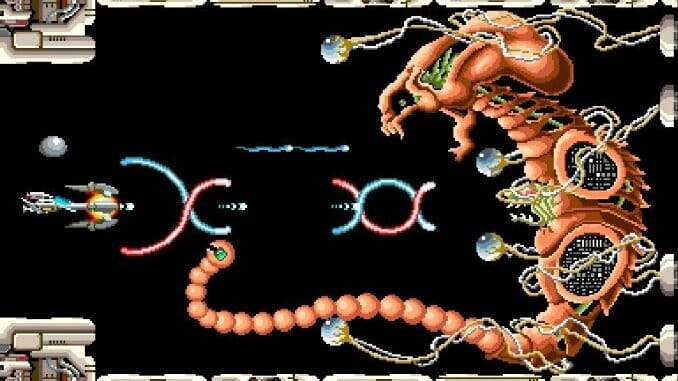

First, let’s explain what I’m talking about. You know those games where you control a spaceship (sometimes it’s a plane, or a person, or an animal, or a dragon, or a hard-headed caveman who has somehow been transported into the candy-colored future, but it’s almost always a spaceship) as it flies, either vertically or horizontally, and shoots its way through increasingly complex waves of enemies who exist solely to kill you or die trying? Your R-Types, your Gradiuses, your Galagas, even? Those are shoot-’em-ups, or “shmups,” as the genre is typically abbreviated. They were huge in the ‘80s, both in the arcade and at home, and then slowly faded in relevance throughout the ‘90s, before ultimately becoming a niche genre with a small but very dedicated following in the 21st century.

It’s not hard to see why shmups fell out of favor with the general public as games became increasingly focused on immersion and storytelling. With its god’s eye view, there’s an inherent disconnect from the mayhem you’re creating in a shmup; you don’t get that direct thrill you feel in first-person shooters like Halo or Call of Duty, or the sense of chaos and dread found in something like the Normandy sequence in 2002’s Medal of Honor: Frontline. And although most shmups have at least a vague outline of a story, they’ve got nothing on even the most rudimentary role-playing game or immersive sim. Shmups were a product of their time and its technological limitations, and as game designers were given the tools to create larger and more interactive spaces, and rewarded by customers for aping the look and feel of movies, the genre understandably started to fade.

I’m not here to complain about that, or call it a shame. It is what it is. But I am here to note that a well-made shmup is as elegant as videogames get—a fusion of grace and precision, where you have to dance between enemies and their bullets while landing your own shots as quickly as possible. There’s an understated purity to the shmup, something that’s easily and immediately understood, that, when combined with the extreme difficulty the genre can be known for, crystallizes into a perfect example of what videogames have to offer.