Games criticism moves in cycles. This isn’t new. It’s sort of a natural occurrence since the medium is still relatively young , so when notable events occur that the entire sphere is concerned with, we end up having the same debates. It’s… frustrating, as a critic, to have to rehash the same argument about once a year, but in a way it helps keep your thoughts fresh.

With that in mind, it looks like we’re talking about skill level again.

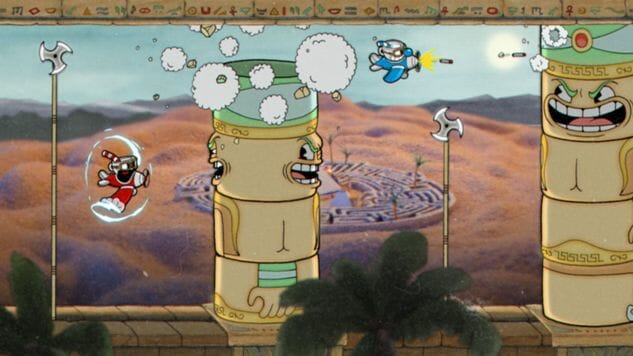

To be more specific, the conversation about the role that skill has in critically analyzing and reviewing games has started up again. In a recent video by Venturebeat, journalist Dean Takahashi struggled to finish the first level of upcoming title Cuphead.

While this incident is new, the debate about the position of skill and challenge in games is far from recent. It was arguably the center of the conversations surrounding Dark Souls. It still is a debate whenever someone mentions older videogames—especially those from the 8-bit or 16-bit eras that, in comparison to more modern titles, can be tough-as-nails. Games have a long and sordid history of difficulty and the balance of challenge to satisfaction.

When a reviewer has trouble playing a game, the instant reaction by many crowds boils down to “If you can’t play this game, why are you in games criticism?” The implication isn’t hard to find: There is an assumption that in order to be a good games critic, you have to be good at games.

It’s a bad assumption, to put it simply.

Videogame culture, writ large, fetishizes skill. An individual’s skill at a particular game determines the validity of the argument posed by that individual, in most common spheres of discussion. But it’s not a really good barometer for critical meaning by any measure.

Games, especially in the modern era (with the aid of Let’s Plays, streaming, and various other methods of content absorption without mechanical interaction) are no longer simply puzzle boxes to unlock knowledge of by solving. Games are stories, conversations between player and world, and conversations between designers and viewers. The act of play itself is but one method of experiencing what we call a “videogame” in modern critical discussions.

This has adverse other effects, as well. Skill fetishization not only adds validity to those critiquing a game, but to those who are making games. An entire other recurring conversation in games criticism revolves around “what is a game” and most of that well is poisoned by skill fetishization as well. At some point, as a culture, games need to leave the skill assumption behind.

There’s nothing inherently good about a game that’s hard, just as there’s nothing inherently good about a game that’s easy. Or, for that matter, anything inherently praiseworthy or dismissable about critics who have a preferred style of game—even if that style is a game that’s not “that hard.” After all, they’re just games.

Dante Douglas is a writer, poet and game developer. You can find him on Twitter at @videodante.