The Last of Us (PS3)

This review contains pretty much every spoiler it could possibly squeeze in. Maybe hold off if you want The Last of Us to surprise you.

Whoever thought the end of world would become boring? Between games, TV, movies, comics, and pretty much every other medium, it feels like the entirety of pop culture exists solely to predict our own destruction. Fictional armageddons cut through multiple Earths a year. With each CGI extinction level event or alien laser-nuke the already diminished impact of all this death grows less powerful. The more the world dies the less it means.

More than any other stereotypical disaster the zombie has become the mascot for the utter defanging of the apocalypse. We’ve already fallen to the zombie horde, and it doesn’t even exist. Unless you’re easily impressed by cracks on consumer culture that were last insightful (if also already kind of corny) in 1978, the zombie genre has grown as shambling and in need of brains as the creatures themselves.

In trying to find a new angle on zombies one of the great clichés of the genre has been created: that the survivors are the true monsters. The Last of Us dredges up that jive (you will shoot at least as many men as zombies), but it rises above such tired conceits on the strength of a relatively subdued tone and believable character development. It’s almost restrained, both for an apocalypse and a videogame. Since everybody’s going to compare this game to The Walking Dead anyway, either consciously or subconsciously, think of The Last of Us as a companion to the first two years or so of Robert Kirkman’s comic book, before it spiraled into repetition and constant attempts to outshock itself. Both whole-heartedly embrace the “people are worse than zombies” cliché, but in both cases the craft and execution are strong enough to transcend it. (Don’t compare it to Telltale’s Walking Dead game, unless you want to make The Last of Us feel both bloated and somehow smaller.)

More than zombies or the survivors that are worse than the zombies, this game is about the relationship between a taciturn old smuggler and a teenage girl who might just be mankind’s savior. Okay, wait, an old bastard redeems himself by protecting a young girl who reminds him of his lost family? A girl who might be everybody’s last hope? That sounds almost as familiar as any old zombie yarn. Again, though, the delicacy with which that relationship is portrayed compensates for some of that familiarity, from the halting dialogue that sounds like real human interaction and that always remains a bit more thoughtful than you expect from a videogame, to the superb voice acting from Growing Pains’ Ashley Johnson and current voice-over superstar Troy Baker (more resonant here than in Bioshock Infinite).

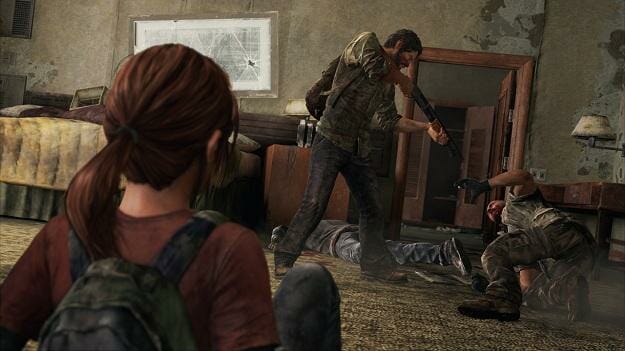

When The Last of Us falters, it is only slightly, and entirely expected. It’s when it acts most like a videogame. One of the strengths of using zombies in a game is that the excessive number of enemies normally found in games is accounted for right there in the concept. In The Last of Us trying to figure out the best tactic to confront or avoid a mass of zombies can be as intellectually thrilling as a good puzzle or strategy game. Stealth doesn’t always work, though, and there’s not always time to prepare, and when The Last of Us turns into a shooter it loses its identity. Like Uncharted, The Last of Us runs through an absurd number of (undead) corpses, with old Joel and immune Ellie killing a few football teams worth of men. The action remains tenser and less cartoonish than most shooters, but the sheer amount of shoot-outs and strangulations still undercut the naturalism of the cut-scenes.