The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask—The Coming-of-Age Story I Wasn’t Ready For

Games Features The Legend of Zelda Majoras Mask

Oftentimes when we revisit a game, we do so as an old friend: curious to see how it’s fared, or striving to capture the feeling of awe it once inspired. Sometimes, it’s because we didn’t give the connection a fair shot, and have decided it’s time to try once more to appreciate the title’s efforts and ideas. Very seldom, however, do we go back because a game made us feel pretty god damn awful, but after the better part of two decades, that’s precisely why I became intent on returning to The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask.

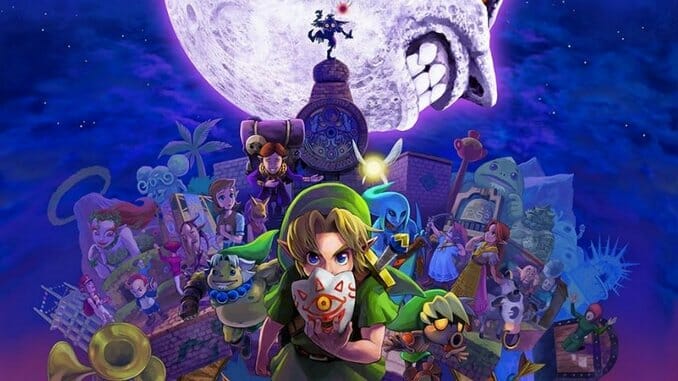

Much like the Neverending Story’s sphinx guardians and the Nightmare on Elm Street VHS sleeve my parents left on the shelf beside our dishwasher-sized television, Majora’s Mask terrified me—but I couldn’t understand why. It lacked flesh-devouring laser beams, third degree burns and bladed fingers, but nevertheless, it filled me with a sense of dread. As a child, I could point my tiny fingers at the eerie music, the moon’s pained grimace, and Skull Kid’s dark giggle, but something else lurked beneath the surface that I couldn’t have possibly understood without years of distance and life lived. And that’s that Majora’s Mask is entirely about the harsh realities of growing up.

As a child, I used videogames as a means to escape reality. My home life was unstable, we were constantly moving and most things in my life were fairly impermanent. But my books, movies and games? I never had to listen to them fight with one another, or bid them adieu when I transferred schools. The worlds and stories bound within them became sanctuaries, but despite my adoration for its predecessor, Ocarina of Time, Majora’s Mask proved itself inhospitable, try as I might to seek shelter. I now realize it’s because Majora’s Mask offers no escape from real life, but revels in the hardest parts of it. In a franchise, genre and medium so deeply rooted in fantasy, it elects to be brutally authentic. It’s a game that demands you grow up.

Majora’s Mask takes place not long after the events of Ocarina of Time— some couple months after you’ve vanquished the great evil, rescued the princess and have thus completed your hero’s journey. However, despite your accomplishments and renown, at the start of the game you find yourself back in the same woods you once called home. And once again, alone. Right from the beginning of the game, Majora’s Mask establishes this is a game about harsh realities, the first one being that even after “happily ever after,” there’s life left to be lived— and it’s not always easy.

After being ambushed, robbed, and transformed into a deku scrub by the mischievous Skull Kid, you meet a man who says he can cure your ailment—which surely must be the doing of that masked menace—if you agree to help him recover the mask Skull Kid stole from him. This man, referred to as the Happy Mask Salesman, repeatedly reassures you that with your abilities and accomplishments, three days is surely plenty of time to retrieve this item, and establishes a firm deadline. Yes, even as a child in a near helpless state, it becomes your responsibility to take on an extraordinarily difficult task with little guidance simply because you’re an overachiever who will figure it out—an overwhelming feeling many of us can relate to.

On the night of the third day, assuming you accomplish everything you need to to progress the game, you confront Skull Kid only to discover his misdeeds have progressed from mischievous to malevolent, and he’s mere moments away from bringing about the world’s end. While this is of course a decidedly bad situation, it’s made significantly worse by your own inability to do anything about it. Despite your accomplishments and prodigal status, you come to find you’re quite simply lacking. It’s a unique, humbling and frightening experience, entering the final fight of a game without the ability to come out of it alive, but it’s the situation we find ourselves in in Majora’s Mask. Instead of prevailing against all odds, we must admit we’re inadequately prepared and look for an exit. Fortunately, you recover the precious item Skull Kid stole from you—the previous game’s titular ocarina—during this battle, and can use it to return to travel back in time to the day our story began and thus narrowly avoid your death.

This time travel mechanic becomes the core of Majora’s Mask gameplay loop, as you attempt to memorize schedules, sequences and events in order to accomplish all you can in your three day time limit before returning to the first day, yet again, with new found items, knowledge and the persistence to try once more. More importantly, however, its accompanying theme of embracing failure becomes the core of its story. You see, in spite of all your greatness, this game forces you to acknowledge limits and mortality repeatedly. To solve a problem, you can’t merely use courage, power or wisdom to overcome. What’s more is this lesson is not only reinforced by Link’s struggle, but is found in every nook and cranny of what is, quite frankly, a pitch-dark game.

Outside of your ocarina, your primary problem solving tool in Majora’s Mask is a collection of masks you obtain through various quests. While every mask comes in handy somewhere in the game, there are three masks in particular—the Deku, Goron and Zora masks—that completely transform your being into that of someone who has died. Two of these masks are directly given to you by spirits you help lay to rest, with the promise that you will take on their identity to help save their homes and loved ones. We watch as they make peace with their life and limitations, and delegate the tasks they wish they could have accomplished themselves to you. The hardest part of this, for me, is coming to terms with how unfair it is that these people didn’t get those three days to go back and get it right—to protect the ones they loved. As frustrating as repeated trial and error might be (as daunting as redundancy, routine and time management are) these characters’ stories give you a new found appreciation for your ability to keep living and trying.

There’s a certain mockery that comes with the phrase “a coming-of-age story” these days, along with this notion that these tales all look a bit something like Life Is Strange or Garden State. While Majora’s Mask might lack an indie soundtrack, it is undeniable that this follow-up to the charming and chivalrous Ocarina of Time—which features the literal maturation of Link—is entirely about emotional growth, something that is impossibly frightening to come to terms with as a child. Hell, it’s quite possible Majora’s Mask was my first experience with anxiety and depression, conditions that would come to follow me my entire life and can, somehow, be even scarier than a boiler room. It was a story I wasn’t ready for and a game I quietly dismissed, despite my complete adoration for The Legend of Zelda series. However, as I look back upon it now, fear gives way to admiration for its unflinching honesty, and while Majora’s Mask might not be an old friend, I’m finally accepting it as a new one.