I was unbelievably focused during high school. During my senior year alone, I took three AP and two IB courses, student directed a production of Macbeth, starred in Into the Woods, and performed in an a capella group all while maintaining a social life and applying to colleges. My productivity peaked, which meant there was only one conceivable way it could go after graduation: down. College started that fall and my attention exploded. For the first time in my life, I forgot to do homework, misremembered quiz dates, and had to force myself to stay not only awake but focused even in the lectures I most anticipated. The only time the bits and pieces of my attention coalesced was when I multitasked. Lectures confined me behind my laptop where I’d surf Wikipedia, play the short lived MacOS slide puzzle widget and, eventually, found my way to mundane browser games. A standard film lecture looked something like this: a Leonard Nimoy–looking professor rambling about [insert country]’s new wave cinema while my laptop was tabbed to an empty Google Doc and three different Wikipedia articles, all of which I ignored to once again try to do well at Threes.

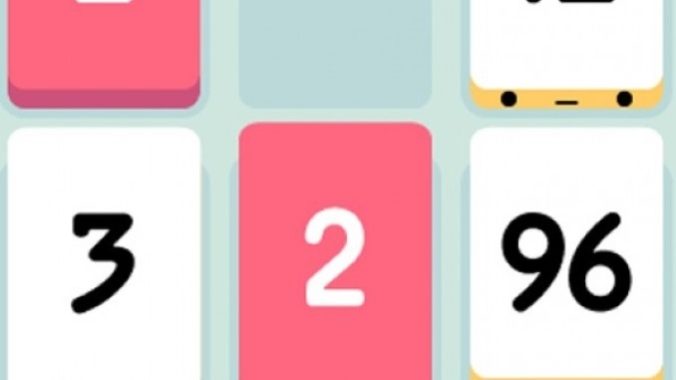

Threes, which turned 10 last week, is an extremely simple puzzle game. Push equal numbered tiles together to create multiples of three—ones and twos add together to make threes, threes to make sixes, sixes to make twelves, and so on and so forth until the end of mathematics or, more likely, until the four by four grid fills with disparate pieces and no more moves can be made. If that sounds familiar it’s likely because the game’s most famous clone, 2048, had a chokehold on middle and high school students everywhere in 2014.

Threes is simple to learn and hard to master; it took two dedicated players three years of intense practice to “beat” the game by obtaining the god-like 12,288 tile. Some players work through the missions or compete on the leaderboard, but I never tried to get a high score or even plan out what direction to swipe based on the upcoming tile. I just swipe and swipe and swipe, head empty, pushing around the little block guys. By playing this way, the game engages my brain just enough to slow it down and help it focus so I could slurp up knowledge. It’s like a digital fidget spinner with more numbers.

I began to play Threes almost daily. Don’t tell my parents, but I passed multiple college courses by mindlessly clicking arrow keys while listening to the professor speak about the cinema of attractions or the difference between liabilities and assets. (Yes, I was a business minor, thank you very much. [And yes, I do regret it, thank you very much.])

It wasn’t until after I graduated college and floundered aimlessly outside the confines of a rigid academic schedule that I questioned why I lacked focus and motivation. I explained my symptoms to my therapist and, without waiting for her reply, exclaimed: “Wow it really sounds like I’m describing ADHD.” I tracked down a doctor to administer the stupidly expensive test and confirmed that my scattered attention wasn’t caused by boredom with Siegfried Kracauer’s writing or apathy toward economics: I had inattentive ADHD. The diagnosis felt revelatory and banal at the same time. All of my distractions, fidgets, and difficulty sticking to schedules now had a medical reason behind them. But that meant they weren’t personal failings that I could fix through self-help books, dedication, and some elbow grease. My brain is wired differently, and I’m still reckoning with that.

In the year after college graduation, I attempted to teach myself better work habits. I blocked out my days in Google Calendar, setting aside specific times for writing fiction, criticism, and pitches all while waiting tables multiple times a week. By the time I entered grad school nine months later, I felt prepared to once again reach peak efficiency. I had worked so hard to create and follow through with plans and I knew that having a class schedule would only help keep me organized. I reasoned that I’d be too engaged with oblique readings about library science and databases to be distracted or unmotivated.

I was wrong. My schedules and motivation dissolved within weeks. My writing dove in quality and quantity, I gave up on readings that proved too complicated or boring, and I dazed through every class. The only things motivating me were anxiety and the large chunk of money missing from my bank account that paid for this misadventure.

I was lost in my attention deficient miasma until partway through my first semester when I stumbled upon Threes again. My professor was talking about Romanian cinema, and my fingers typed in the game’s url as if recalling a ghost. I started playing to pass the time and found myself focused for the first time in months. This wasn’t the hyperfocus that pushed me to 100% Super Mario Bros. Wonder in a week, nor was it the lackadaisy through which I had been sloshing for months. It was simply focus, the small prickle in your brain that tells you what you’re doing is interesting and, to some small degree, important. Threes did not magically fix my life and save my grades, but it did remind me that I could rein in my attention and gently direct it toward something, just as I had done in college. It was okay that I needed some help doing that because there would always be a simple game offering a numerical solution.

Mik Deitz is a freelance writer and former Paste intern. They inhale stories in videogames, films, TV and books, and have never finished God of War (2018). Yell at or compliment them on Twitter @dietdeitz.