The nature of an economy is to rise and fall—to experience peaks and recessions, sometimes to devastating effect, sometimes limited to a certain sect of an economy. We all have or will experience a recession in our lifetimes, from the Great Depression, to the 2008 recession, to even the most recent COVID-19 recession. Then there’s the Great North American Videogame Crash of 1983.

In the early 1980s, arcade games experienced a massive boom with approximately 24,000 arcades in the United States alone. Games also thrived at home, with then-sophisticated consoles and games growing a massive audience. As the industry continued to grow more popular and profitable, companies began to flood the market with inferior product, both trend-chasers hoping to capitalize on this new, and industry leaders like Atari, whose poor home version of Pac-Man and tie-in with E.T. were both notorious bombs. After all, who wants to play a bad game? In 1983, Atari announced an $180 million loss in their third quarter, ending up with an overall $500 million loss that year. The home gaming market effectively felt dead.

Enter: Nintendo, the Japanese videogame company that would save North American gaming. Nintendo began to conduct aggressive research about gaming demographics, and it came back that boys were playing videogames in droves. Boys were playing more than girls so much that Nintendo’s ads aimed their product primarily towards boys. As those boys became teenagers and men in the ‘90s, the games industry continued to market almost exclusively towards them, making girls feel excluded. After initially appealing to boys and girls in the early ‘80s, videogames were redefined as masculine; they were sexy, they were how you got the girl, they were an escape—they made you a real man. The videogame was, effectively, reinvented and revived for the culture at large.

But all of that was 30 years ago or more. What does that have to do with 2023? At a glance the videogame industry is booming. Games like The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, Marvel’s Spider-Man 2, and Diablo IV, and even movies and TV shows like The Last of Us and Five Nights at Freddy’s, have been released to huge success over the past year. Everything is fine! This has nothing to do with the past. Right?

Take a closer look and you’ll find that there’s already been an estimated 9,000 jobs lost in videogames this year alone. Naughty Dog, CD Projekt Red, Team17, and Epic Games have all laid off significant staff since this summer. Volition shut down, Embracer Group is looking to sell Gearbox Entertainment, and Ubisoft was reported to be closing several of its European offices. E3 is dead.. Games have been delayed while others, like CrossfireX and Sega’s Hyenas, have been cancelled altogether. So what’s going on? Well it’s certainly not like the ‘80s—people are still buying games en masse, and it certainly isn’t due to an influx of faulty consoles or bad games. Sure, Cyberpunk 2077 may not have done too well at first, but that’s nothing in comparison to the dumpster fire of Quaker Oats’ 1982 Sneak‘n Peak videogame.

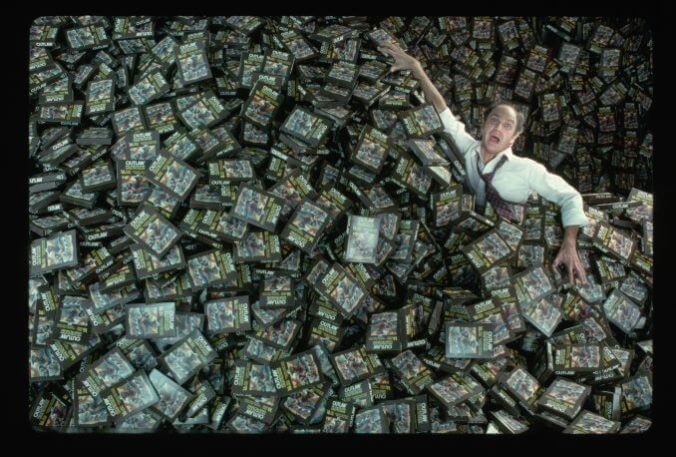

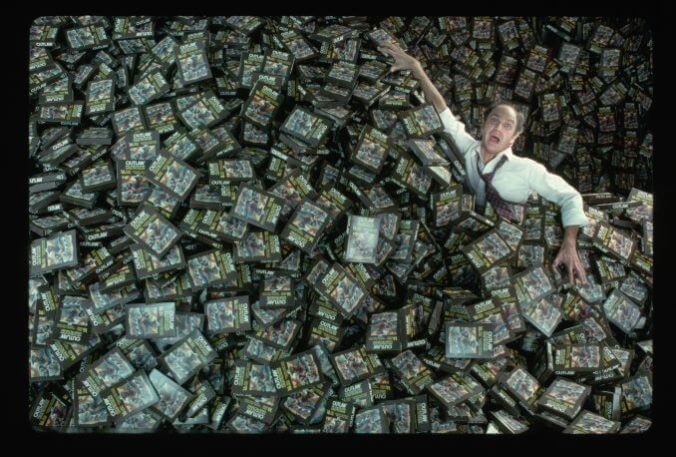

This photo from 1983 accompanied news stories about that year’s videogame crash.

This photo from 1983 accompanied news stories about that year’s videogame crash.Is it possible to ever again see a crash of the magnitude of the 1980s with the popularity and ubiquity of videogames today? Probably not. That being said, the 1983 crash had more to do with game sales than our current situation, which is concerned with the projects and people involved in making the games. Game sales aren’t struggling, but budgets aren’t always reasonable, margins can be slim, and continual layoffs force workers to work longer and harder. It doesn’t seem all that sustainable. And while I don’t think we’ll reach the fever pitch of 40 years ago, it still stands that the two situations exist along the same framework.

What I’m interested in from that framework are the cultural implications of a modern videogame crash. I will never forgive Nintendo for starting the trend that turned gaming into a boys’ club. (Shigeru Miyamoto, if you’re reading this, I love your games but watch your back.) Despite that, I have to point out that videogames were saved in the ‘80s by social research. We enjoy such volume and variation in videogames today because Nintendo discovered who played games the most and shifted their marketing that way. The modern videogame landscape no longer reflects the male ubiquity Nintendo uncovered—in the US 47% of console players and 50% of PC players are women. In 2022 approximately 40% of US gamers were non-white and 16% were part of the LGBTQIA+ community. 30% of gamers identified as disabled in 2021. Gaming is realistically no longer a boys’ club, but incidents like 2014’s GamerGate or a continuous lack of diversity in Esports would have us believe otherwise.

So my question is this: if we experience another videogame crash 40 years on from the one that changed the current landscape, is it possible that developers today will learn from Nintendo’s success and conduct the research necessary to broaden and revive the industry? It’s my argument that while the downturn we’re seeing now is largely due to the elements of an economic recession, we could also easily tie it to the videogame industry still struggling to meet the diversifying needs of a diversifying audience, and so that audience feels compelled to neglect videogames in some capacity.

Even if the current industry isn’t seeing all of the same factors that drove the collapse of 1983, it remains possible that studios can at least try to learn from and recreate what dug videogames out of the hole 40 years ago. That is market research that pays better attention to the female, disabled, queer, Black, and other audiences that make up a huge but often overlooked percentage of gamers. Just as it was impossible to ignore that boys once made up almost the entirety of gamers, it’s now impossible to ignore that that is no longer true. Would it be objectively bad if the videogame industry continued to experience a downturn and crashed at 1983 levels? Of course! I love videogames and I am not denying that that would negatively affect both world cultures and world economies, but it’s also true that the peak and fall is the natural cycle of an economy. The only thing I can hope and push for now is that, as the industry picks itself back up, videogame studios will see how an inclusive gaming environment could only be a boon to their market. Who’s to say if any developer would take the time to conduct such wide scale market research, and who’s to say that it wouldn’t be exploited. But something bad is happening in videogame development right now, something that needs a counterweight—who’s to say it won’t be the reinvention of gaming practices and production?

Maddie Agne is an intern at Paste.