Where Did You Go, Viewtiful Joe?

While COVID-19 has undeniably impacted release schedules for many bigger-budget games in recent years, a cursory look at Steam or other online distribution platforms shows we are in an era defined by a constant deluge of new stuff, a never-ending stream of titles which we can only take a small sample of. Since the rise of the indie gaming scene over the last decade and a half, developers have retrodden almost every gameplay paradigm imaginable, reviving dormant genres and blazing new trails. The rise of crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter has created a wave of spiritual successors to beloved franchises, such as how Koji Igarashi reunited with other Castlevania alums to develop their own pseudo-sequel, Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night. And even if not directly associated with old-school devs, it feels like just about everything you can imagine has been revitalized or reconsidered, with all manner of Metroid homages, JRPGs, beat ‘em ups, shoot ‘em ups, and even Golden Eye-likes seeing modern incarnations. It feels like there are precious few rocks left unturned from gaming’s past. And then there’s Viewtiful Joe.

Released in 2003 for the GameCube, Viewtiful Joe was developed by a team of Capcom veterans who had previously worked on several of the company’s most high-profile outings. It was helmed by Hideki Kamiya, the director of Resident Evil 2 and Devil May Cry, who would go on to lead the Bayonetta series at PlatinumGames. The other two eventual founders of PlatinumGames, Shinji Mikami (Resident Evil, Resident Evil 4) and Atsushi Inaba were producers on the project, with a host of programmers, sound designers, and artists who had worked on recent studio hits making up the rest of the internal Capcom unit “Team Viewtiful.”

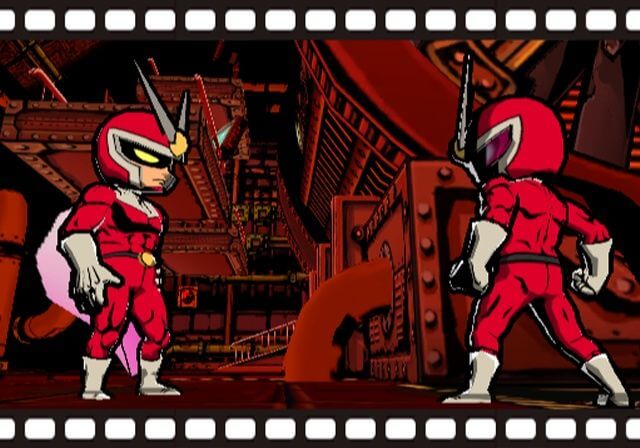

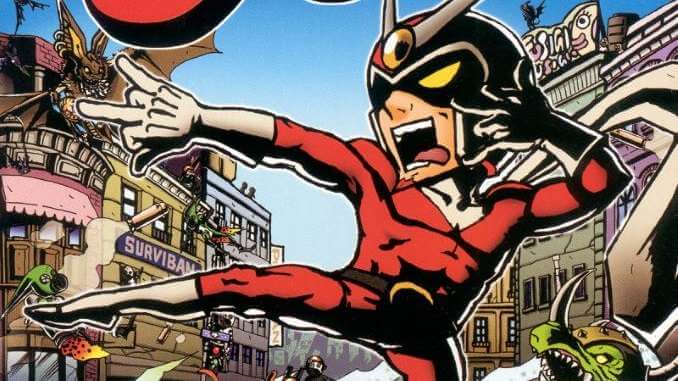

Although there were traces of the company’s previous releases in the title, specifically in its links to character-action games like Devil May Cry, Capcom’s beloved brawler wasn’t quite like anything released before or since. You play as Joe, an incredibly annoying film nerd who gets sucked into the world of cinema. Heavily inspired by tokusatsu superhero fiction, our protagonist is transformed into a Kamen Rider-styled crimefighter and must work his way through a host of bad guys so he can fulfill the legacy of his mentor Captain Blue. The story is largely presented with a tongue-in-cheek affectation, reveling in genre antics like villains of the week, big robots, and spandexed vigilantism while also poking fun at its cliches. Its writing can be amusing, but its mechanics are where it stands alone.

Viewtiful Joe is a side-scrolling brawler and platformer that differentiates itself through novel filmmaking-themed abilities called “VFX Powers,” each allowing Joe to control Movieland’s reality. By holding the left trigger, you activate slow-motion, making it easier to dodge incoming attacks, strengthening your blows, and enabling impossible feats like redirecting bullets with a well-timed strike. Hitting the right trigger speeds up time, letting Joe move so fast that the screen fills with his afterimages. The last ability toggles close-ups, increasing his damage and granting access to new moves. On top of their combat capabilities, each mode is also used to solve environmental puzzles, like slowing down time so you can line up a slot machine or speeding things up so Joe’s punches ignite flammable substances. You can even mix and match two of these powers at once to capitalize on enemy vulnerabilities. While these maneuvers are essential to the flow of the experience, using them drains the VFX meter, and when empty, Joe reverts to his regular non-impressive form, taking increased damage and losing access to his reality-warping abilities. While the VFX bar refills quickly, much of the learning curve comes from managing this resource carefully to ensure you get the most out of these powers without overdoing it.

Although Viewtiful Joe is frequently categorized as a beat ‘em up, this descriptor doesn’t quite capture the experience. The most obvious disqualifying element is that while those titles let you move vertically, here you are restricted to an XY-plane like in other 2D platformers. And semantics aside, the experience feels fundamentally different because it encourages a different kind of defensive precision. For instance, in Final Fight offense is defense, and you’re incentivized to pre-emptively hit and grapple enemies to ensure the opposing thugs get in as few punches as possible. By contrast, in this title you want foes to take shots so you can turn the tables. Attacks are clearly labeled with warning icons that indicate a low or high swing. Highs can be ducked by hitting down on the right analog stick, while lows can be leaped over by hitting up. A successful dodge puts an enemy in a dizzy state, and if you hit them with a slow-motion blow while they’re off-balance, it sets up a beatdown session where every combatant in the vicinity becomes vulnerable to slow-mo strikes. This enables stylish combos where after ducking a wayward punch, you’ll tear through a screen full of robot henchmen, their metal frames letting out gratifying crunches as you send them colliding for massive damage. This emphasis on avoiding telegraphed attacks changes the cadence of gameplay compared to traditional beat ‘em ups, creating choreographed fistfights that evoke the flair of the kaijin-punching shows that inspired it.

Even almost 20 years after it was initially released, the core tenets of its combat feel fresh. The heavy tells on enemy attacks set up for tough but fair bouts, and the empowering film reel-bending abilities steal the show. Through these episodic adventures, you’ll redirect missiles to take down enemy fighter jets, rhythmically dodge onslaughts from special forces androids, and deal with a variety of tough bosses that are equal parts puzzle and execution test. While there are a few rough edges, like the brutal boss rush in the penultimate level or some of the grating writing, things hold up remarkably well. However, in some sense, this freshness isn’t exactly surprising, as nothing has come along to iterate on this particular style of experience and render its predecessors obsolete. These games represent an abandoned path of design, a rare well-received franchise that hasn’t seen any form of revival, formal or otherwise.