WWE 2K14 (Multi-Platform)

When Vince McMahon, the owner of what was then called the World Wrestling Federation, bought WCW from Time Warner in 2001, he became the last man standing in the weird little pop culture nook that he already dominated. This purchase had two significant impacts on the wrestling industry. Both are integrally linked to one another, but one was immediate and obvious, whereas the other slowly revealed itself in time, and only after the company changed its name to World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE). WWE 2K14, the fine new wrestling game from 2K Sports, would be a drastically different game without either of these currents guiding the last 12 years of wrestling history.

Firstly, and most obviously, the American wrestling industry became a de facto monopoly overnight. After two decades of expansion and consolidation, McMahon had defeated all his rivals, either driving them out of business or buying them outright. Wrestlers could look for work in Mexico or Japan, or try to scrape up money on the American indie circuit, but if they hoped to make a good living at home they’d have to stay on good terms with McMahon. Many well-known wrestlers of the 80s and 90s basically saw their careers end when the last WCW program aired in March 2001.

Secondly, after ignoring his rivals and barely acknowledging the history of his own company, McMahon finally saw the value in nostalgia. When a wrestler joined McMahon’s promotion in the 80s and 90s, their pasts were almost always ignored. They were often given new names and gimmicks and essentially rebranded as new performers under the WWF aegis. They usually couldn’t take these names or gimmicks with them if they jumped to another company, often undermining their ability to draw money or fans for their new employer. Ray Traylor was still a decent worker when he jumped to WCW in 1993, but people didn’t care about him without the name the Big Bossman, which McMahon owned. But without any major rivals, and with the tape library of almost every significant American promotion at his disposal, McMahon realized he could profit off the past without benefitting anybody else.

Over the last decade the WWE has become a museum. In 2004 they restored a long-dormant Hall of Fame (which is a Hall in name only—there’s no physical location) that exists to reward performers loyal to McMahon with a bit of attention and money after their wrestling days are over. The company releases several DVD box sets a year devoted to the careers of specific wrestlers and the histories of entire organizations (September’s overview of Bill Watts’ Mid-South promotion is a must-own for true fans of the fake sport). WrestleMania, the “Showcase of the Immortals”, is now basically the showcase of the semi-retired, with wrestlers like the Rock, Brock Lesnar and McMahon’s son-in-law Triple H (too busy running the company to perform regularly) popping up in time for a WrestleMania feud and then taking several months off afterward. The biggest match at each WrestleMania has become the Undertaker’s annual defense of his undefeated streak, which is usually the only match he wrestles every year. The company that once ignored the past is now defined by it.

For the second year in a row, WWE’s annual videogame also depends heavily on history. Last year’s WWE ‘13, the last WWE game from the now-defunct publisher THQ, primarily touted its “Attitude Era” mode, where players could recreate famous matches from the company’s late 90s heyday. WWE 2K14 broadens its historical focus outside a single era and encompasses the entire 30 year history of WrestleMania.

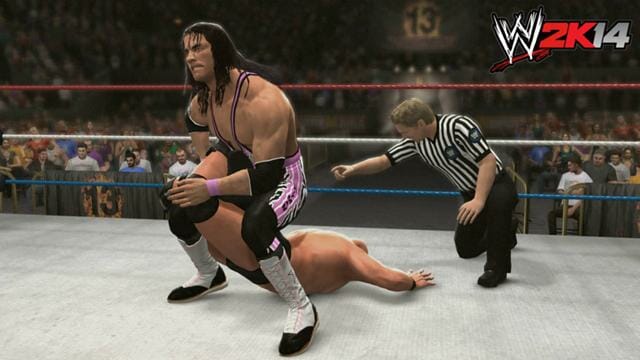

The “30 Years of WrestleMania” mode features at least one match from every WrestleMania. It’s divided into a handful of distinct time periods—the “Hulkamania Era” covers the first nine WrestleManias, the “New Generation” era focuses on the mid 90s rise of Bret Hart and Shawn Michaels, and the “Attitude Era” returns for a curtain call—and if you meet every goal for a match you unlock the wrestlers, managers and arenas for regular play within the game. It’s a nostalgia simulator, letting you step into Randy Savage’s boots when he wins his first WWF World Championship at WrestleMania 4, or guide John Cena to victory over Batista at WrestleMania XXVI.

As history, “30 Years of WrestleMania” is a weird cartoon reflection of actual events. Matches are often introduced with exciting video packages detailing the backstory, before cutting to the videogame versions of wrestlers reenacting actual interviews with their real voices. Performing certain actions in-game will trigger cut-scenes that recreate memorable moments from the real matches (like Hogan body slamming Andre the Giant at WrestleMania III, or Hogan and the Ultimate Warrior almost knocking each other out for a dual ten count at WrestleMania VI). But legal realities prevent the game from ever using the name “WWF”. The original commentary is unusable, leading to Jim Ross and Jerry “The King” Lawler” anachronistically calling matches that happened a decade before they worked for McMahon. The first WrestleMania is represented by Andre the Giant’s body slam challenge with Big John Studd and not the actual main event—Mr. T’s likeness is apparently too expensive. It’s history with many of the major facts changed or ignored. This doesn’t detract from the game, but it is a distraction, and reminds us that history only matters to WWE as long as they can make a buck off it.

There’s a sidebar within “30 Years of WrestleMania” built around the Undertaker’s undefeated streak (he’s 21-0 at WrestleMania, dating back to 1991). There’s a mode where you control another wrestler trying to end the streak—the Undertaker is basically the ultimate game boss, countering almost every move and routinely pinning you within minutes. Conversely you can play as the Undertaker and wrestle a gauntlet match against the game’s entire roster—I pinned 41 wrestlers before Brock Lesnar finally made me submit to an abdominal stretch. This section includes a graphic that lists every one of the Undertaker’s WrestleMania matches and who he defeated. Certain years don’t list an opponent. Either the Undertaker beat some kind of unnamed entity at WrestleMania XIII instead of Sid Vicious, or else WWE couldn’t or didn’t want to reach a deal with Sid to use his name and likeness.

Wrestling fans are used to this cavalier attitude towards history, though. Almost every DVD set comes with a documentary about the subject in question, and often they’re more interested in relaying the official WWE viewpoint than legitimate impartial analysis. If we have to take canned Lawler jokes and WWE references during the videogame version of Randy Savage and Ricky Steamboat’s WrestleMania III match, well, at least we’re getting to recreate a match that’s considered one of the best and most important of all time.