The 10 Best Animated Movies of 2024

The best animated movies of 2024 continued a trend we’ve seen in recent years in which the biggest titans of the art form ultimately fell a bit flat, in comparison with their more deft and nimble competitors. The likes of Disney landed with a bit of a thud, and you won’t see the overburdened likes of Moana 2 here even though it’s still making an absolute killing at the box office. Pixar at least snuck back into the rankings thanks to the relative strength of another box office juggernaut, Inside Out 2, but suffice to say there are no other billion dollar behemoths here. Rather, the best animated movies of 2024 are a far more creative and varied bunch, touching on modern anime classics such as Look Back or Maboroshi, or the unclassifiable beauty of Chicken for Linda or Flow. The beloved duo of Wallace & Gromit even graced us with their return to the realm of feature films for the first time since 2025! If that’s not a major animation event, then I don’t know what is.

So with that said, here are the 10 best animated movies of 2024:

10. Mars Express

Director: Jérémie Périn

Mars Express is an unabashed genre flic from director Jérémie Périn and French studio Everybody on Deck. The noir thriller takes us on a contemplative tour of a thoughtfully considered future, where traveling between Lunar and Martian colonies is as easy as flight today.

We follow Aline Ruby (Morla Gorrondona), some sort of cop investigating a mysterious disappearance and murder linked to unusual behavior among the humanoid robots of a patron corporation—and it’s filled with all the tropes of the setting and story you might expect. It’s a setting where humanoid robots (think Asimov) and transhumanist tech (think Oshii) are commonplace, prodding at the boundary between life and creation.

Mars Express’ art direction isn’t particularly moving, lacking striking visuals that could easily live alongside its inspirations. Its script (from Périn and Laurent Sarfati) is similarly just a bit too quiet for its own good—there’s no moment where the hooks sink in to you. Mars Express rides instead on moments like a cat’s skin zipping off to reveal a mechanical frame beneath, or in considering all the implications of artificial mind and body duplication (ranging from espionage to sex work). If you linger in its world long enough for a second viewing, there’s much to appreciate. —Autumn Wright

9. The Wild Robot

Director: Chris Sanders

The Wild Robot is the final animated film, at least for now, to be produced entirely in-house by DreamWorks Animation. It’s by no means the end of the House that Shrek Built; three DreamWorks cartoons (relying, reportedly, on outside studios) are scheduled for 2025, and Shrek himself will soon return, doubtless armed with a bunch of meme references and hacky music cues. In the meantime, though, here is a DreamWorks animated feature that doesn’t begin with the protagonist introducing themselves and their world via voiceover. Here, even, is a DreamWorks animated feature that doesn’t feature much upfront dialogue at all, surely a terrifying prospect for a studio whose creative signature has long been pure yammering. At times, The Wild Robot feels almost elegiac – or is that just what happens when DreamWorks drops their worst habits and dedicates themselves to serving as a genuine creative competitor to their old rivals at Disney.

Movies that attempt to convey the bittersweet experience of parenting to a younger audience are usually Pixar’s department, but Sanders has dabbled in this area with How to Train Your Dragon and The Croods. The Wild Robot is closer to those movies – in tenderness, in the energy and variety of its character designs, in fluidity of its animation, and in reference-light humor – than many other DreamWorks productions, and, for that matter, it’s better than some Pixar movies, too. Yet despite Sanders’ abiding interest in remaining an animator, rather than a calculating one-man board room, there is something – forgive me – programmatic about The Wild Robot, particularly in its attempts to tug at the heartstrings. —Jesse Hassenger

8. Inside Out 2

Director: Kelsey Mann

No one, and I mean absolutely no one, looks back on their time in middle school and thinks, “Wow those years were great. I would love to go back.” Fraught with changing bodies, overnight growth spurts and outsized emotions, the years are turbulent both for the children going through puberty and for their parents trying to understand the stranger living in their house. But, curiously, not many movies and TV shows are aimed directly at this demographic. They either skew too old (Euphoria, a show designed to give adults everywhere nightmares) or too young (Disney’s delightful Descendants trilogy). Pixar to the rescue! Inside Out 2, the sequel to the Oscar-winning film, revisits Riley (now voiced by Kensington Tallman) in the full-blown throes of adolescence.

Like Toy Story 3 or the more recent IF, Inside Out 2 is also a reflection about what childhood things get lost as you get older. “Maybe this is what happens when you grow up. You feel less joy,” Joy says. More poignant than an out-and-out tearjerker, the observations of Inside Out 2 may still get adults a little misty. Life does not get easier as you get older. —Amy Amatangelo

7. Maboroshi

Director: Mari Okada

We all have those memories that, for better or worse, we can’t seem to get rid of. Formative experiences that are coarse and awkward but end up continually shaping us, laying dormant until a sudden association jostles them to the forefront. While some may be definitively good or bad, many more inhabit a strange middle ground between the two, moments that can be looked back upon with a mixture of nostalgia, regret, longing and relief that they’re finally over with. Maboroshi, an animated film from prolific writer/director Mari Okada (Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, O Maidens in Your Savage Season, Toradora, Hanasaku Iroha) and the equally busy studio MAPPA (Jujutsu Kaisen, Attack on Titan, Vinland Saga), literalizes these types of inescapable recollections.

Through its deeply flawed cast and Peter Pan-esque world caught in stasis, Maboroshi communicates the suffocation and silver linings of being trapped within a particular point in time. Part elegy and part celebration of the past, it makes for an evocative, unusual ghost tale.

The story begins when Masamune (Junya Enoki), a 14-year-old living in Mifune, Japan, witnesses an explosion at the local factory. But this isn’t any normal accident. The boom seems to rip their town from the very fabric of time, trapping its denizens in an endless limbo where the seasons never change and no one grows older. Some believe this a punishment handed down by the god of a nearby mountain, which has been mined for generations, but definitive answers are difficult to come by. —Elijah Gonzalez

6. Orion and the Dark

Director: Sean Charmatz

A children’s movie written by Charlie Kaufman; that’s a sentence that reads like a wry joke in a movie written by Charlie Kaufman (I’m Thinking of Ending Things). But it’s actually a real thing. Kaufman has adapted Emma Yarlett’s preschool picture book, Orion and the Dark, into Netflix’s animated film of the same name. And let me tell you, Orion and the Dark is the most Kaufman-esque children’s movie you could possibly imagine, replete with oodles of existential anxiety, a metafiction narrative and a surprisingly emotional payoff.

If Kaufman were to ever admit that he basically conscripted Yarlett’s simple tale—of Dark hanging out with a kid who is afraid of him—as a conduit to write a semi-autobiographical expose of how neurotic little Charlie grew up to be the screenwriter we know and love today, I would not be surprised. Luckily, his script found the perfect animation collaborators in first-time director Sean Charmatz, production designer Tim Lamb and art director Christine Bian who have created a visual landscape that translates the writer’s weirdness into something charming and digestible for both kids and adults. —Tara Bennett

5. Chicken for Linda

Directors: Chiara Malta, Sébastien Laudenbach

Homecooked family meals are a classic kind of halcyon memory, as familiar smells and tastes bring back a time when things seemed a bit simpler (or at least, that’s how it worked in Ratatouille). However, what if instead of immersing you in an idyllic past, a particular familiar dish drudged up things you’d rather forget? Chicken for Linda! is a puckish film from directors Chiara Malta and Sébastien Laudenbach that gets at this question, using creative animation to portray a family coming to terms with an old meal and all the heartbreak that comes with it.

Following a parenting mishap, Paulette (Clotilde Hesme) promises her rambunctious eight-year-old daughter Linda (Melinée Leclerc) a favor as a make-good. Unfortunately for Paulette, what Linda wants most is chicken with peppers, the same dish that ended up as Paulette’s late husband’s final supper. And not only does this request come with the tremendous weight of unresolved grief, but it’s also damn inconvenient–they’re all out of poultry and the supermarkets are closed due to a general strike. Bound by her word, Paulette sets out to find chicken as the pair encounter chaos and camaraderie in the streets of France. —Elijah Gonzalez

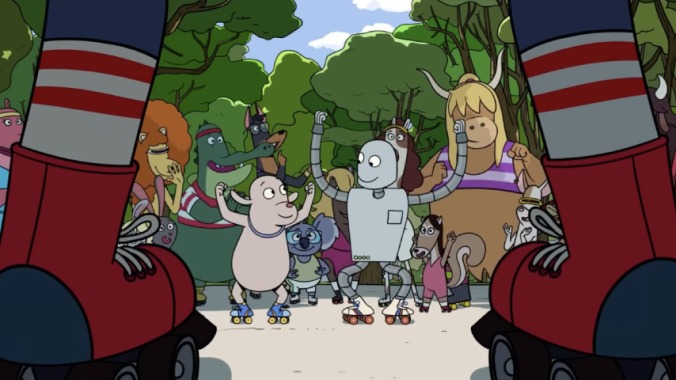

4. Robot Dreams

Director: Pablo Berger

Robot Dreams was at least to some extent lost in the hubbub of this past year’s Academy Awards for one primary reason: Pretty much no one in the U.S. had actually had a chance to see the film at the time. Nevermind the fact that it competed for the Oscar for Best Animated Feature back in March–all of the conversation at the time was revolving around choices either far more populist (Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse) or from creators so revered that they’ve achieved mythological status, as in Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron. It’s unsurprising that Spanish director Pablo Berger’s sweet but emotionally resonant Robot Dreams was more or less swept under the rug, but its eventual arrival in U.S. theaters and streaming services in 2024 has allowed American viewers to finally realize what they had been missing: One of the most charming and tear-inducing, wordless stories of friendship we’ve been gifted in recent memory.

Robot Dreams is a classic story of loneliness and friendship, as created in the relationship between Dog, a mute resident of a beautiful version of NYC occupied by anthropomorphic animals, and Robot, the sentient automaton who becomes his closest companion. On its own, that premise might provide enough material for a short film, but Robot Dreams ventures into unexpectedly poignant territory when a series of accidents forces the two apart. Again, one expects convention to step in, for Robot Dreams to coalesce into a story about finding your friend against all odds and refusing to give up. But instead, it eyes these events with both a pragmatism and emotional maturity that is refreshingly and distinctly realistic: Dog and Robot both find a next phase in their lives, without needing to let go of how much their time together meant to both. Few would-be comedies or dramedies of this sort are so adept at holding both POVs at once: The simultaneous sense of profound loss at having drifted away from a former close relationship, but also the acceptance, cherishment of the memory, and hope for a future of new, novel experiences. Robot Dreams recognizes that emotions don’t happen sequentially, but all at once, and captures it in beautifully fluid animation as it brings to life a lovingly rendered portrait of New York at the same time. —Jim Vorel

3. Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl

Directors: Nick Park, Merlin Crossingham

It’s a testament to the effectiveness of an animated story if it can immerse you in its setting and familiarize you with the essence of its characters in a matter of minutes, even if the setting and characters in question are beloved icons that are nevertheless almost totally unknown to the viewer. And that makes the instantly approachable nature of creator Nick Park’s work all the more apparent in the upcoming, Netflix-hosted feature film Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl–within minutes of sitting down to stream a press preview, it began to feel like I’d known the titular duo for decades already. That’s how winningly and simply effective the archetype of these characters remains to this day–it doesn’t matter if you don’t know a thing about them; they still win you over immediately.

This kind of joyful, cheerful excess is the through-line of Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl, from the duo’s massively overengineered home filled with gadgets to solve nonexistent problems, to the steadily mounting action sequences that make up the film’s third act, the highlight of which involves a slow-speed canal boat chase that somehow builds itself to life-or-death stakes. The light satire on technological dependency, meanwhile, is appreciated but almost unnecessary in comparison with the simple joys of the lovingly detailed stop-motion animated movements and expressiveness. The film’s entire arc, in fact, is more or less entirely predictable, but it just doesn’t matter–it’s an old-fashioned charmer that only registers as that much more refreshing for the lack of similarly animated fare in the modern industry. And yes, that includes Aardman Animations Limited’s own disappointing return to Chicken Run with last year’s Dawn of the Nugget. Unlike that would-be franchise, the central, wholesome allure of Wallace & Gromit remains undiminished. —Jim Vorel

2. Look Back

Director: Kiyotaka Oshiyama

Look Back, the 2021 manga by Chainsaw Man mangaka Tatsuki Fujimoto, follows the coming-of-age of fourth grader Fujino as she discovers and asserts her desire to draw manga. Her story is shaped by an unexpected rival-turned-accomplice Kyomoto, a truant who takes up the pencil after reading Fujino’s school newspaper comics, yet quickly outpaces the drawing skills of her hero.

But beyond the technical craft, what makes Look Back so appropriate as an animated film is its relationship to time. Time must pass for us too when Fujino draws at night, at school, at the park, when she runs in the rain, sobs in an empty bedroom; and Oshiyama lingers. Look Back guides our attention to something less romantic than the ideals of the craft. It’s work. And all the animation is itself more work. To make audiences sit with Fujino as she draws, how many hours did that take?

Look Back is a requiem for art lost to violence, to circumstance, to conformity. It is also an argument to create. It pleads with us to see the work–in the folds of clothes, reflected in eyes, in its own credits. Look Back is not the platonic animated form of The Boy and the Heron, which felt like inevitable creation. Look Back is the labor of the Tower of Babylon that reaches the heavens and, in Ted Chiang’s story, breaches the reservoir, revealing the shape of the world. Their toil could not reveal any more than they knew, but rather simply allow them to glimpse at how ingeniously the world had been constructed. Few climb the tower with empty hands. —Autumn Wright

1. Flow

Director: Gints Zilbalodis

It sounds sort of like a Disney movie, only without enough plot – so maybe like an early Illumination bid for huggable franchising, computer-animated in the painterly textures of a recent DreamWorks feature: a cat, a dog, a lemur, a bird, and a capybara must work together to navigate a grand adventure. Only these animals don’t talk, much less yammer or crack wise, and, beyond a few minor conveniences, they behave more or less as animals might be expected to. The adventure, too, is a bit less magical and a bit more menacing than your average kiddie fare: There has been some kind of massive, possibly global flood, with little evidence of contemporary human civilization in sight, and some fanciful-looking whales that suggest an alternate world. Whatever the situation, never specified in part because the movie has no dialogue at all, this Latvian animated feature takes the audience through it with immediacy, empathy, and artistry. And for all its separation from the dynamics of contemporary American studio animation, this is a pretty great family film, and one that might well expand a child’s cinematic vocabulary to boot. It’s a testament to the power and flexibility of its chosen medium. – Jesse Hassenger