The Queer Tragedy of The Children’s Hour Is More than a Trope

In recent years, the 1961 film The Children’s Hour has garnered a reputation for its “outdated” depiction of queer shame and its “bury your gays” ending. But a film is more than the sum of its parts, not bits and pieces to be plucked off and filed away into a folder of tropes, and what The Children’s Hour was trying to say with its characters back in the ‘60s is still fairly radical for a mainstream queer film.

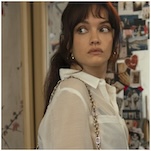

Adapted by director William Wyler and screenwriter John Michael Hayes from Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play of the same name, The Children’s Hour stars Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine as Karen and Martha, two young schoolteachers whose lives are destroyed when a cruel child tells her grandmother Mrs. Tilford (Fay Bainter) a tale about the teachers’ supposed lesbianism. Pupils are immediately pulled from the school, and when Karen and Martha lose a libel suit against Mrs. Tilford, they are left in social and financial ruin. Their only friend, Karen’s fiancé Joe (James Garner), loses his job for continuing his association with them, and later, Karen, overwhelmed by these troubles, dissolves her engagement with Joe.

Though it is true that The Children’s Hour ends tragically, with Martha struggling over her own very real feelings for Karen and then committing suicide, the suicide doesn’t take the form of the traditional “bury your gays” structure, which was originally used to appease moral codes and then often later used to narratively banish ambiguous or complex characters from the story so that the other more “normal” characters could have a conflict-free future.

In The Children’s Hour, Martha is a fully-realized central character, and her death affects those around her in a complicating way, not a simplifying one. She isn’t the strange, othered person who must be relegated to the graveyard for other characters to live more comfortably. Nor is she only there to serve as a lesson. Instead, she is a character the audience is meant to relate to, with the later reveal of her queerness likely meant to keep audiences from holding her at arms-length from the start.

The Children’s Hour makes a point not to judge Martha’s queerness, and the characters who do—like Martha’s dreadful aunt, Mrs. Tilford and the gawking townspeople—are all framed as antagonists. Martha’s love for Karen is treated as wholly human, jealous at times, but never any different from what one might expect from a heterosexual attachment. The film even includes a shot of Martha watching Karen lovingly, and it is framed as any other romantic shot might be. Though Martha is clearly suffering, she is not set up to deserve suffering—and she is not suffering alone. She is not the only victim.

We are meant to identify with all three victims (Martha, Karen and Joe) as a trio, and they are not much distinguished from each other, beyond Martha’s personal feelings for Karen. These are young people who are just getting on their feet, who have to deal with the headaches of starting a business, having little money and awful aunts. They’re designed to be sympathetic and relatable. When trouble comes, they’re all overwhelmed by it in varying ways.

Who we aren’t supposed to identify with are the “righteous” members of society, with whom many audiences then and now would likely relate if the film were structured differently. Though it is a cruel child who sets off this chain of events, it is a respectable older woman with power and influence who truly causes the irreparable harm, all in the name of “protecting the children.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-