Happy 4th of July: The best horror movies of the year so far should accompany a good BBQ and the celebration of the grotesque spectacle of American imperialism. Don’t feel like partying much tonight? At least one of the films below is about a scary new illness; at least one is about the violent co-opting of Black bodies for pathetic white means. Crack open a cold one and rest assured no one can take away your right to watch, unblinking, as your dog seizures to the noise of colorful explosions in the street. God bless.

Here are our picks for the 10 best horror movies of 2020 so far:

After Midnight Release Date: February 14, 2020

Release Date: February 14, 2020

Directors: Jeremy Gardner, Christian Stella

Stars: Jeremy Gardner, Brea Grant, Henry Zebrowski, Justin Benson

Rating: NR

Runtime: 83 minutes

Hank (Jeremy Gardner) has a problem: Abby (Brea Grant), his longtime girlfriend and the weathervane of his existence, has up and left with only a vague note to explain her sudden disappearance. All Hank has to hang onto now is his family’s old home, which he and Abby had made their home together, plus a bottomless case of peanut wine. Oh, also, there’s that damn monster that batters Hank every night after the clock strikes 12. That’s a problem, too. After Midnight could be read as anything other than a horror film, but if there’s a worse horror to live with than the horror of knowing your short-term future is going to be defined by monster attacks, well, Gardner doesn’t care. Following his usual tack, he wrote this movie, co-directed this movie and put himself in front of the cameras while they rolled: There’s more budget to speak of than his other work (like The Battery), considering the involvement of effects studio MastersFX (see: Tales From the Crypt: Demon Knight), but most of the money goes toward…well, wait for the final 10 or so minutes to find out. Everything that’s left over goes toward creating a sadsack world for Hank to live in and pity himself in, his stunted emotional growth being the bugbear holding him back from going anywhere with his life and with Abby. “Manchildren but make it scary” sounds like a terrible elevator pitch, but Gardner’s been making low-budget, high-tension, higher-atmosphere movies in his sleep for his whole career, and After Midnight is the most refined example of his vision yet. —Andy Crump

Color Out of Space Release Date: January 24, 2020

Release Date: January 24, 2020

Director: Richard Stanley

Stars: Nicolas Cage, Joely Richardson, Madeleine Arthur, Brendan Meyer, Tommy Chong, Julian Hilliard, Elliot Knight

Rating: NR

Runtime: 110 minutes

Known first as a great author and second as an enthusiastic Hitler stan, Lovecraft imagined his personal fears—particularly of “the masses”—into wholly unimaginable entities, his work so tethered to his pants-wetting neuroses that adapting it for a visual medium feels like a masochist’s chore. That makes Richard Stanley perfect for translating Lovecraft’s short story “The Colour Out of Space” into a feature-length film: The last time he tried making a horror movie it was 1994, and the feature was The Island of Dr. Moreau. Turning Lovecraft’s words into coherent cinema is a comparative walk in the park, and in Color Out of Space, Stanley gaily strolls ahead with a palette sporting every shade of purple, adding splashes of phlox here and smears of thistle there before coating the screen entirely in heliotrope hues by the end. “Color” is the key word of the movie’s title and the most important tool in Stanley’s work belt: The longer the horror Lovecraft describes on the page endures and infects the world around it, the more vivid Stanley’s imagery becomes. The second most important tool, perhaps expectedly, is Nicolas Cage, starting off the 2020s on the right foot with another Cage-ian horror performance after his stellar work in 2018’s Mandy. If there’s an actor better-suited than Cage for conveying the experience of losing one’s sanity under Lovecraftian duress, the industry hasn’t found them yet. Cage, like Stanley, occupies an existential plane visited by no one else. Lovecraft’s words give Color Out of Space a foundation; Cage gives it character. He might exist in a vacuum, but he doesn’t act in one: The rest of the cast falls in the orbit of his unhinged eccentricity, much as the meteorite’s presence warps all nature around it. Cage, by being Cage, makes everyone around him better, or if not better, then stranger. —Andy Crump

The Deeper You Dig Release Date: June 5, 2020

Release Date: June 5, 2020

Directors: John Adams, Toby Poser

Stars: John Adams, Toby Poser, Zelda Adams

Rating: NR

Runtime: 95 minutes

Call it a family affair. Husband and wife team John Adams and Toby Poser wrote and directed The Deeper You Dig together. Adams stars in the movie as Kurt, Poser as Ivy and their daughter, Zelda Adams, as Echo. Going into business with loved ones is a bad idea in nine out of 10 cases. Here, that bond functions like cement holding their movie together, giving real weight to The Deeper You Dig’s unadorned spartan aesthetic. Kurt’s renovating a rickety old home on his own, which is for the better because he’s not the social butterfly type. One evening, he goes out for drinks, has one too many, and in a terrible split second of distraction on a snowy ride back, he runs Echo down by accident. Immediately after, not at all by accident, he hides her corpse in his tub, and eventually goes so far as to dismember her and bury her in the woods. Meanwhile, Ivy, her mother, a medium who long ago lost her gift for communicating with the other side, desperately begins searching for her missing child and regains her spiritual talents in the process as Echo’s ghost begins haunting and taunting and maybe also possessing Kurt.

The Deeper You Dig is uncomplicated in terms of craft. Adam and Poser find an angle and stick with it instead of mucking about with flashy nonsense. Theirs is a far more effective approach than any hyperkinetic and self-regarding form of filmmaking for a story like this, where the deliberately paced plotting reveals chills in their due time without vaulting ahead to force them on the audience well before it’s necessary. The Deeper You Dig’s austerity is only its second greatest strength, of course, the first being the Adams-Poser effect, but it’s still a strength worth celebrating. —Andy Crump

Extra Ordinary Release Date: March 6, 2020

Release Date: March 6, 2020

Directors: Enda Loughman, Mike Ahern

Stars: Maeve Higgins, Will Forte, Claudia O’Doherty, Barry Ward, Valerie O’Connor

Rating: R

Runtime: 93 minutes

It can be difficult to organically thread “romance” into horror-comedy, broadening a film to equally weigh a third major genre, but it’s the quirky relationship fodder where Extra Ordinary ultimately displays its greatest strength. This Irish indie never truly takes the frightening side of paranormal investigation seriously—it’s a true comedy all the way, and probably stronger for it—but it’s the unexpectedly quiet, thoroughly human lead performances that make it memorable. Those come from Irish actors Maeve Higgins and Barry Ward as two unassuming but uniquely talented people, imbued with abilities that allow them to touch the spirit plane rather more easily than they’re able to socialize with living, breathing humans. Higgins in particular really owns the character of Rose Dooley, imbuing her with a good-natured and immediately relatable soft-spokenness on top of an aura of melancholy that belies her ability to bring closure to spirits stuck in limbo. The scenes the two have together contain a certain warmth, a feeling that two people have been brought together who complete one another nicely—if only Ward’s ex-wife wasn’t still in the picture (in poltergeist form). Nevertheless, it’s Will Forte’s charismatic performance as washed-up prog rock star/demonic cultist Christian Winter that is likely to draw more U.S. viewers to Extra Ordinary, given that he’s the film’s most recognizable star. He makes the most of the opportunity to play another deeply eccentric character in a career that has been full of them, although his performance almost feels like something from a different movie when compared to the more grounded focus on the relationship between Higgins and Ward. That central duo, and their emerging rapport, make Extra Ordinary a heartfelt, breezy entry that gets a lot of mileage from very few moving pieces. —Jim Vorel

The Invisible Man Release Date: February 28, 2020

Release Date: February 28, 2020

Director: Leigh Whannell

Stars: Elisabeth Moss, Oliver Jackson-Cohen, Harriet Dyer, Aldis Hodge, Storm Reid, Michael Dorman

Rating: R

Runtime: 110 minutes

Aided by elemental forces, her exquisitely wealthy boyfriend’s Silicon Valley house blanketed by the deafening crash of ocean waves, Cecilia (Elisabeth Moss) softly pads her way out of bed, through the high-tech laboratory, escaping over the wall of his compound and into the car of her sister (Harriet Dyer). We wonder: Why would she run like this if she weren’t abused? Why would she have a secret compartment in their closet where she can stow an away bag? Then Cecilia’s boyfriend appears next to the car and punches in its window. His name is Adrian Griffin (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), and according to Cecilia, Adrian made a fortune as a leading figure in “optics” (OPTICS!) meeting the self-described “suburban girl” at a party a few years before. Never one to be subtle with his themes, Leigh Whannell has his villain be a genius in the technology of “seeing,” in how we see, to update James Whale’s 1933 Universal Monster film—and H.G. Wells’ story—to embrace digital technology as our primary mode of modern sight. Surveillance cameras limn every inch of Adrian’s home; later he’ll use a simple email to ruin Cecilia’s relationship with her sister. He has the money and resources to peer into any corner of Cecilia’s life. His gaze is unbroken. Cecilia knows that Adrian will always find her, and The Invisible Man is rife with the abject terror of such vulnerability. Whannell and cinematographer Stefan Duscio have a knack for letting their frames linger with space, drawing our attention to where we, and Cecilia, know an unseen danger lurks. Of course, we’re always betrayed: Corners of rooms and silhouette-less doorways aren’t empty, aren’t negative, but pregnant with assumption—until they aren’t, the invisible man never precisely where we expect him to be. We begin to doubt ourselves; we’re punished by tension, and we feel like we deserve it. It’s all pretty marvelous stuff, as much a well-oiled genre machine as it is yet another showcase for Elisabeth Moss’s herculean prowess. —Dom Sinacola

Sea Fever Release Date: April 10, 2020

Release Date: April 10, 2020

Director: Neasa Hardiman

Stars: Hermione Corfield, Dougray Scott, Connie Nielsen, Ardalan Esmaili

Rating: NR

Runtime: 89 minutes

Sea Fever, Irish director Neasa Hardiman’s feature film debut, begins with trademark horror calling cards: Siobhán (Hermione Corfield), an unpopular yet talented marine biology student, finds herself on a run-down fishing trawler as a research requirement. However, her Celtic-red locks immediately draw distrust from the rest of the tight-knit crew; lore warns having redheads aboard a ship brings bad luck. The voyage of the trowler, named the Niamh Cinn-Oir, quickly descends into chaos after the ship’s captain, Gerard (Dougray Scott), is explicitly instructed by the Coast Guard to maneuver around an “exclusion zone.” He, along with co-captain and wife Freya (Connie Nielson), shake their fists at the order due to the high density of fish in the now off-limits zone. Without telling any of the crew or Freya, of course, Gerard takes the Niamh Cinn-Oir through the exclusion zone anyway. The trowler is soon hit with a force that stops it in its tracks, and the wood walls of the hull begin to ooze blue slime, prompting Siobhán to dive and remove what the crew expect to be some sort of barnacle. Underwater she encounters a many-tendriled bioluminescent creature tethered to the ship, reaching out with a blue, glowing arm as she frantically swims away. Sea Fever quickly morphs into part creature feature, part parasitic contagion piece, part eco-fatalist cautionary tale. It does not promise clear resolution or put forth a hopeful sentiment toward humanity’s perseverance; Sea Fever demands the viewer grapple with their own ideas of self-importance and sacrifice, which just happen to have a compounded relevance right now. While Hardiman couldn’t have foreseen the elevated commentary her film would take on six months after its TIFF debut, it’s refreshing to have a film that takes itself so seriously by refusing to sacrifice its moral stance in order to satiate the anxieties of viewers—anxieties that have become more prescient than anyone could have imagined. —Natalia Keogan

We Summon the Darkness Release Date: April 10, 2020

Release Date: April 10, 2020

Director: Marc Meyers

Stars: Alexandra Daddario, Amy Forsyth, Maddie Hasson, Keean Johnson, Logan Miller, Austin Swift, Johnny Knoxville

Rating: R

Runtime: 91 minutes

Roughly 30 minutes into Marc Meyers’ We Summon the Darkness, the tables turn. The twist isn’t telegraphed. Paranoid viewers might catch the scent of something “off,” the way people with hyperosmia know the milk’s gone bad before opening up the carton, but noticing the clues that Meyers, screenwriter Alan Trezza and the film’s main cast—Alexandra Daddario, Maddie Hasson and Amy Forsyth—leave on the screen takes a little deductive reasoning and a lot of psychological study. No one gives anything away. Instead, Meyers carefully pulls the truth from the set-up, and in the process hints at not a small amount of relish on his part. He’s having fun. A good twist should be fun, and We Summon the Darkness does indeed have a good twist, but Meyers, Trezza and especially Daddario appear to realize that the pleasure of a twist isn’t the reveal, it’s figuring out how to hide the twist in plain sight. This is, at first, a horror story about teenagers uniting under the banner of heavy metal in 1980s America, a time when God-fearing Christian bedwetters saw proof of devil worship everywhere they gawked and blamed the rise of Satanism on objectively awesome things like Dungeons & Dragons and Dio. Half an hour in, We Summon the Darkness still is that story, but told from the perspective of religious vultures who happily exploit the fears of the flock to profit the church. It’s a ferocious joy to watch, particularly in light of how well We Summon the Darkness holds back on secrets. Tipping the hand too much would be easy; the tells only become clear after the fact, couched in a choice of words here, a moment of hesitation there, a dose of forced enthusiasm there. For as unrestrained as things get, it’s the initial restraint that’s most memorable. —Andy Crump

The Wolf House Release Date: May 1, 2020

Release Date: May 1, 2020

Directors: Joaquín Cociña, Cristóbal León

Stars: Amalia Kassai, Rainer Krause

Rating: NR

Runtime: 75 minutes

Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León’s Spanish-German language film The Wolf House is equal parts surreal, tragic and disturbing, due to both its uncanny stop-motion animation style and the real-world inspiration from which it draws. The film follows the perilous journey of María (Amalia Kassai), a young German woman who has narrowly escaped the jaws of a Nazi cult but must now outrun a hungry wolf hot on her trail. The cult María flees is based in Southern Chile, making it an evident parallel to Colonia Dignidad, a German sect established in Chile in the early ’60s by a man named Paul Schaefer, who was about to go on trial for child molestation in West Germany before he was granted sanction to enter Chile. As the wolf draws nearer, María stumbles upon a small house in the middle of the woods. She quickly makes herself at home. The house is ostensibly abandoned, save for two small pigs living in squalor in one of the bathrooms. María vows to raise the pigs as her own children, naming them Pedro and Ana. She clothes them, feeds them the little unspoiled food remaining in the house and excitedly tells them that she will teach them “everything that she knows.” But María finds it difficult to navigate what the cult has imparted on her, and complicated feelings surrounding pleasure, punishment and eugenic aesthetic ideals begin to find themselves seeping into her lectures to Pedro and Ana.

Accordingly, The Wolf House can feel sickening at points, mostly due to the ever-morphing vessels that serve as avatars for María, Pedro and Ana. Their corporeal forms emerge crudely shaped from clay, ooze onto the walls and windows as painted figures, grow bloated and disjointed as paper-mache, stitched together and dressed with felt and plush. The titular lycanthropic abode was a real house that the filmmakers utilized to create the film’s uncanny, human-scale dioramas, the diligent craftwork of the years-long undertaking captured in the finished product’s every frame. By confronting the state-sanctioned violence in Chile’s recent past, Cociña and León construct a physical space to reflect the emotional space one must inhabit to process these traumas and to confront the evil figures that may still live within them. —Natalia Keogan

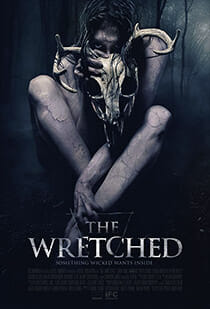

The Wretched Release Date: May 1, 2020

Release Date: May 1, 2020

DIrectors: Brett Pierce, Drew T. Pierce

Stars: John-Paul Howard, Piper Curda, Jamison Jones, Zarah Mahler, Azie Tesfai, Kevin Bigley, Blane Crockarell, Ja’layah Washington

Rating: NR

Runtime: 96 minutes

Ben’s (John-Paul Howard) summer has started out on the wrong foot: His parents are in the middle of a separation that’s calcifying into a divorce, and he’s been sent to live with his father, Liam (Jamison Jones), for the season, working at the local marina in lakeside Michigan and taking shit from hyper-privileged brats. He also has the attention and affections of cool girl Mallory (Piper Curda), and the couple renting the house next door to his dad’s leave the light on when they screw, so it’s not all bad, except for the ancient flesh-eating witch lurking in the woods. Save for minor details like smartphones and Google image searches, Brett and Drew T. Pierce’s The Wretched could be mistaken for an unseen 1990s flick dug up like a lost relic of its era. The film shares in common DNA with classics like The Faculty, in which wolves skulk among the herd and only the kids are open-minded enough to realize it, but The Wretched doesn’t fetishize its cultural touchstones, or function only as genre nostalgia. Practical FX work and creature design help, too, as essential to what distinguishes The Wretched from its influences as the Pierce brothers’ writing. They build tension and avoid playing coy: Something sinister is in the woods, they let their viewers know upfront, and they have a blast dropping clues and hints for Ben to decipher while Liam loses himself in a relationship with his new girlfriend, Sara (Azie Tesfai). The Wretched’s gore quotient likely will fall on the low side for splatter addicts, but the film understands when viscera is called for and when withholding is better. Its best scares tend to involve a glance into the darkness, where nothing should be but in which evil lurks, or through binoculars, which throws the malevolent presence lingering at The Wretched’s edges into sharp relief. The movie can go to gross places and brings appropriate sobriety to sequences of little kids being consumed by the slimy beldam posing as their mother, but the Pierce brothers’ prevailing tone is “haunted house ride”: Even at its most gruesome, The Wretched stays light on its toes. —Andy Crump

Zombi Child Release Date: January 24, 2020

Release Date: January 24, 2020

Director: Bertrand Bonello

Stars: Louise Lebeque, Katiana Milfort, Mackenson Bijou, Wislanda Louimat

Rating: R

Runtime: 103 minutes

What does and doesn’t constitute cultural appropriation? Tracking down your classmate’s mambo aunt and begging her, in between offering her wads of money, to cast a voodoo spell on your pretty boy ex? French filmmaker Bertrand Bonello’s latest picture, Zombi Child, is half historical account, half racial reckoning—entirely ambitious, and equally as ambiguous. Bonello is white, just like Fanny (Louise Labeque), his bratty, lovesick protagonist, a student at the Légion d’honneur boarding school, which Napoleon established for the purposes of educating the daughters of men awarded the, well, the Légion d’honneur, and where entry remains a hereditary right. To her, voodoo is a means to an end, that end being that Pablo (Sayyid El Alami), her beau, has his soul bound to hers. To Katy (Katiana Milfort), a Haitian voodoo priestess, and to Mélissa (Wislanda Louimat), Katy’s niece and Fanny’s literary sorority sister, it’s a spiritual discipline, an aesthetic and a way of life, rich with beauty but carefully marked by caution signs to keep practitioners from making decisions they’ll regret. Zombi Child treats voodoo as a character in its own right, a living organism to be revered and not screwed around with. Naturally, Fanny’s first instinct upon hearing of Mélissa’s ancestry and her connection to voodoo is to try and screw around with it, as if voodoo is a class of magic in D&D rather than a set of syncretic religions practiced in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Louisiana and Brazil. Mélissa tries educating Fanny and her friends on what voodoo means to her as the granddaughter of Clairvius Narcisse, on whose life Zombi Child is based: In 1962, Narcisse (played here by Mackenson Bijou), died, was buried, then returned to life as a zombie, meaning he was actually mickeyed with a melange that made him seem dead, buried alive, then dug up by plantation owners who forced him to harvest sugar cane as their stupefied thrall. Zombi Child isn’t a horror movie. It does, however, take notes from horror grammar, and the audacity of Bonello’s filmmaking is enough to inspire madness. But the heart that drives Zombi Child forward beats in the pursuit of cultural justice. The film wrestles with identity, and with whiteness especially, and with France’s reputation as an icon of revolution alongside its unflattering reputation as a colonial power guilty of inhuman atrocities. The conclusions Bonello draws are inevitably vague, but the most important message is obvious: That’s cultural appropriation. —Andy Crump