Despite Fascinating Archival Footage, Spaceship Earth Flounders When Examining Whiteness and the Colonial Lens

Matt Wolf’s latest documentary provides stunningly captured 16mm footage regarding the Biosphere 2 project, but little meaningful conversation surrounding the deeper issues concerning colonization.

For the entirety of 1991 through 1993, eight individuals were sealed in what would be a completely self-sustaining vivarium in an attempt to make strong scientific headway in the prospect of space colonization. Director Matt Wolf’s Spaceship Earth is an ambitious blend of archival news coverage, 16mm footage spanning 25 years and talking head interviews centering around the oft-forgotten Biosphere 2 project.

Yet for a documentary so laser-focused on the intricacies of this dynamic group of “Biospherians” and the counterculture mentality of the ’60s that inspired them, there is little examination of space colonization as manifest destiny and who would be granted the opportunity to start anew if Earth—referred to in the film as Biosphere 1—is ultimately made uninhabitable by the very humans who populate it.

“What we’re upset [about] is that there’s no multiculturalism inside,” says an unnamed young Black man visiting Biosphere 2 in an archival interview. He stands among a group of other young Black people; a young woman by his side chimes in, playfully: “I would like to know what a young Black woman from Brooklyn would do in a biosphere, huh?”

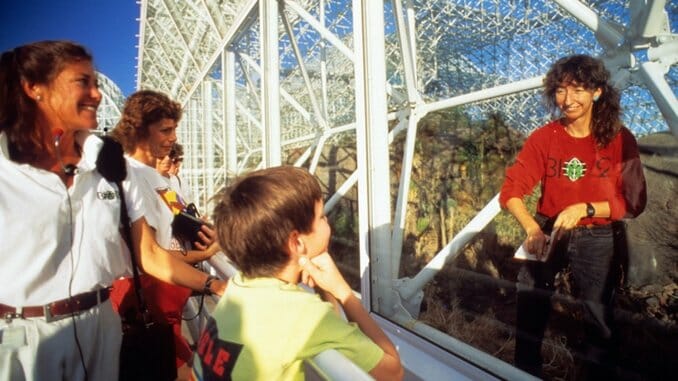

This short clip, enmeshed among other interviews with tourists visiting Biosphere 2 in the remote Arizona desert as the experiment percolates behind glass walls, is presented almost as a cut-away gag when, really, it serves as one of the boldest questions brought up during Spaceship Earth about the nature of colonizing. Where, exactly, do those whose ethnic and cultural roots have been irreparably altered by Western colonization fit in amid a new frontier of space exploration?

It’s true that inhabiting a desolate planet and creating a livable habitat from scratch does have different implications than displacing, enslaving or committing genocide against an area’s population in order to exploit their resources and plant a flag. But there would undoubtedly be a deep social inequality highlighted by who would be chosen to repopulate in space after the Earth is left barren.

Much of the history of the individual Biospherians, and their varied experiences at the Synergia Ranch commune in New Mexico before their involvement in the project, reflects a nomadic attitude and a desire to ravage what the world has to offer. It culminates in the building of a ship and traversing the world by sea, then eventually combing the Earth’s habitats in order to curate flora and fauna to replicate the many terrains of the globe for Biosphere 2. It’s this dual assumed identity of vagabond and world-builder that makes the Biospherian plight so interesting, as they both desire to have complete control over their own fate yet aspire to have a hand in the construction of the future of humanity.