Fat City at 50: John Huston’s Ode to the Down-and-Outers

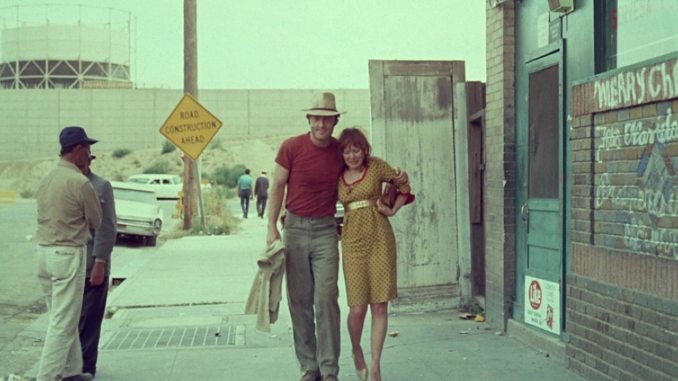

“When you say you want to go to Fat City, it means you want the good life…The title is ironic: Fat City is a crazy goal no one is ever going to reach,” Leonard Gardner said of his first novel in 1969. He’d soon adapt it into the screenplay for a film directed by John Huston. Look up any plot synopsis or logline for Huston’s 1972 Fat City and you’ll be pitched a Stockton, California-set rise and fall narrative about one boxer at the end of his career and the other at the start of his, who will eventually come to blows in some presumably stunning finale showdown.

This couldn’t be further from the truth of the story Gardner and Huston are here to tell. Fat City is about boxers as much as Citizen Kane is about selling newspapers. Opening and closing with the woesome tones of Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” it’s about our need for companionship in the face of life’s ongoing adversities.

For Billy Tully (Stacy Keach) and Ernie Munger (Jeff Bridges), stepping into the ring doesn’t come with promises of glory and making it to the big leagues. Sure, that’d be nice, but they’re here to earn a few bucks to pay the bills—to keep the lights on in Billy’s dingy, ramshackle one bedroom where you imagine a cockroach screaming past if you dare pick up the week-old newspaper crumbled up into a ball on top of the plate of old food in the corner. Hoping to get back into shape, Billy runs into Ernie at the gym in the film’s opening scene, seeing in him something he likely once saw in himself: A contender.

Fat City isn’t about a rivalry that forms between these two men. It’s about a bond that builds between two worn-out losers just trying to get by. Billy is about to hit 30, looks like he’s passing 40 and hasn’t had a fight in a year and a half. Ernie is a fresh-faced 18 and never had a fight in his life. Billy knows he’s well past his prime. When the two begin to spar in that first scene, he almost immediately pulls a muscle and has to stop. But he gives Ernie the details for his old manager Ruben (Nicholas Colasanto) and tells him that he could make it if he wants to give it a chance. Ernie follows the advice and starts booking some fights, but from the jump we know this isn’t going to be Rocky. Hell, this isn’t even going to be Cinderella Man.

Ernie loses his first fight pretty quickly and is brought back into the locker room where Ruben has all his other fighters on the card that night. You can smell the sweat permeating the wet air. As Ernie’s recovering from the bout, his team takes his shorts off and tosses them to another boxer to put on. “They’re all bloody,” the other fighter complains as he begrudgingly puts them on. This is Fat City’s boxing world, one far from the flash and pizzazz Hollywood loves to embrace in the arena of sport. The fights are scrappy, rough around the edges, with men striving simply for another day, not for fame and glory.

That mentality is reflected in how Huston and the great cinematographer Conrad Hall stage the fights. There’s no adrenaline-pumping music getting us up on our feet, no fast-whirling cameras to give us the thrill of being in the ring. Hall brings the camera up close with the actors, peeling the sweat off their bodies as they get knocked out in the first round; the kind of anticlimax these guys are used to. They’ve faced it all their lives.

A well-known figure in Hollywood at this point in his illustrious career, there wasn’t a better choice to direct Fat City than Huston, as odd as it may seem on the surface. A mammoth success in his early days with films like The Maltese Falcon (somehow a directing debut), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and The African Queen, Huston was on a brutal downswing of flops by the time Fat City hit his desk, coming off titles like Reflections in a Golden Eye and A Walk with Love and Death. He understood the trials and tribulations of someone who had the fame that’s not even in these men’s reach, and seeing that bloom fall off the rose, trying to pick it back up out of the dirt.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-