Long Live the Digital Flesh: Videodrome and Our Social Media Selves

Movies Features David Cronenberg

Social media allows us to create alternate versions of ourselves, idealized clones that exist solely in cyberspace. Log into, say, Facebook and go back eight or ten years. Peruse the tone and content of your posts from the era, then compare them to how you feel you really were at the time. You’ll likely come out with two distinct personalities. Two people: One made of flesh, the other of the new, the digital flesh.

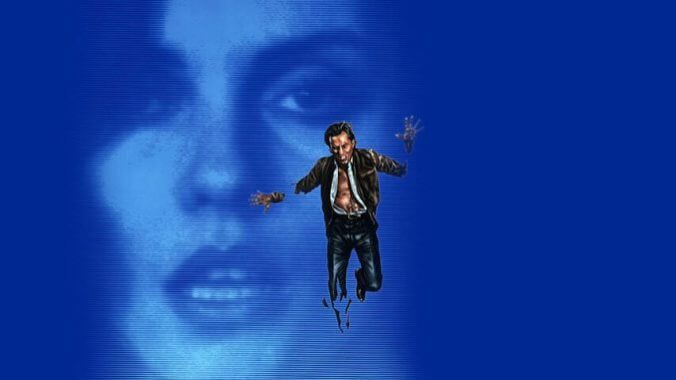

Videodrome, David Cronenberg’s 1983 body horror opus, was conceived long before the Internet—let alone social media and smartphones—was available for consumer use, but it remains prescient about the future of our digital identities. It follows the greed-driven exploits of Max Renn (James Woods), a programmer for a sleazy local Toronto channel that broadcasts graphically violent and erotic content in order to compete with mainstream networks. Max seems to have found his big hit with “Videodrome,” an obscure, pirated bit of content that shows ultra-realistic scenes of torture and murder without any attempt at plot to tie the sequences together.

As Max salivates after licensing Videodrome for public consumption, a hidden signal inside the transmission induces hallucinations that break the barrier between the objective reality of the video and Max’s deepest sexual and violent urges. Which leads to the most Cronenbergian image in all of Cronenberg-dom: Max develops a VCR/vagina in his stomach, which invites fleshy Betamax tapes that pulsate with orgasmic yearning. Blurring the line between the organic and the mechanical is certainly not a new subject for Cronenberg—one that reached its apex with 1996’s Crash—but Videodrome perfectly blends his uniquely surreal body horror with his prescient vision of a world that defines the next stage of human evolution via video communications.

A key character in that evolution is “media prophet” Professor Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), who serves as a mentor figure in Max’s hero’s journey. When the audience first meets O’Blivion, he appears on TV inside a TV show that’s meant to discuss the desensitization of violence and sex in mainstream media. The addition of a video screen within a TV program adds an extra layer of artificiality to O’Blivion’s presence, which is precisely his intent: “The television screen has become the retina of the mind’s eye,” he calmly explains to the host. “That’s why I refuse to appear on television, except on television.” He freely admits that O’Blivion is not his real name (which would have been a bit too on-the-nose if it was, even for ’80s Cronenberg standards): “Soon,” he clarifies, “we will all have special names. Names designed to cause the cathode ray tube to resonate.”

Of course, the technical tools available to Cronenberg at the time to convey a future communicated entirely through the artificiality of the screen were analog video and the CRT TV signal. Replace the cathode ray tube with the screen of a smartphone; imagine the alternate names and identities that people infuse into that tech. As Max further investigates O’Blivion’s connection to Videodrome, he comes across new age church The Cathode Ray Vision, where homeless people can watch hours of television in order to reintegrate themselves into what O’Blivion believes is our new reality. O’Blivion’s daughter, Bianca (Sonja Smits), explains the church’s mission: “Watching TV will patch them back into the world’s mixing board.” The alternative world emanating out of the screen is more real in their minds than their personal experiences, so more TV is the only solution for those who try to re-establish themselves into the new normal. Compare this premise with how odd it seems nowadays to see anyone in public who’s not glued to their screens, scrolling through their feed as their only tangible connection to society. When Max wants an audience with O’Blivion, Bianca explains to him that the professor hasn’t interacted with another person in 20 years. He records video responses and sends the tape to the subject.

Bianca adds, “Monologue is his preferred form of discourse,” which immediately brings to mind the status updates or the dead-end arguments we engage with on social media. The concept of monologue as discourse is a contradiction in terms, but it also aptly describes the way we mostly communicate. Even comments sections with heated discussions serve as a series of monologues instead of a naturally occurring conversation. The extended time between responses, the lack of a personal connection creates a new mode of human communication and interaction, one that drives us further away from the intimacy we crave as social animals.

On his video response to Max, O’Blivion explains that “whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore, television is reality, and reality is less than television.” O’Blivion’s new-age philosophy becomes widespread prophecy through Cronenberg’s almost serenely matter-of-fact depiction of the character. When Max becomes obsessed with meeting O’Blivion face-to-face, he comes across a tragicomic reality: O’Blivion’s been dead for 11 months, and has been communicating with the outside world through thousands of pre-recorded tapes.

Bianca has been operating as her father’s “screen,” essentially catfishing his followers. It turns out that O’Blivion created Videodrome as “the next phase in the evolution of man as a technological animal.” The hallucinations caused by the signal create what’s first assumed to be a tumor, but turns out to be a new organ that eases humanity’s next evolutionary transition into a society experienced through the TV—or phone—screen. Time will tell how much our addiction to the screen and to social media will actually affect our physiology, but the concept of neurological enhancements experienced by a life lived via the screen isn’t anything new.

O’Blivion’s preferred mode of discourse leads to a realization that “public life on television is more real than private life in the flesh.” Bianca adds a chilling reality to this exposition: “He wasn’t afraid to let his body die.” O’Blivion believed that in the modern world, the afterlife exists inside data. As Max’s hallucinations intensify to the point where he can’t distinguish between the video world and reality, he eventually declares his new consciousness to be the “Video Word made flesh.” Instead of his otherworldly experiences leading him to dispel the artificial reality he created for himself, he chooses the opposite fate, and decides to let his mind merge with video, “letting his body die.” Max precedes this final act in his evolution with the mantra “Death to Videodrome! Long live the new flesh!”

In 1983, Cronenberg conceived of Videodrome as a bizarre (but on-brand) conduit for expressing his anxieties regarding a future where life behind the screen would be more validated than the one in front of it. In 2020, where does the new flesh go from here? We may be primed to become like O’Blivion, our alternative digital self existing long after our old flesh is dead and buried, our loved ones continuing their relationships with us through skewed versions, through identities we’ve chosen rather than through representations of our true, messed-up selves. Then again, according to Cronenberg, we may not have a choice.