This post is part of Paste’s Century of Terror project, a countdown of the 100 best horror films of the last 100 years, culminating on Halloween. You can see the full list in the master document, which will collect each year’s individual film entry as it is posted.

The Year

Well, here we are: The bottom of the late ’30s horror trough. For all the reasons we discussed in yesterday’s post on 1937, the industry had completely bottomed out on the horror genre at this point. None of the major Hollywood studios felt like going up against Joseph Breen’s Production Code Administration in getting their horror stories certified without major revisions and constant nitpicking, and the consensus seemed to be that the finicky public had lost interest in the gothic monster movies that were all the rage at the beginning of the decade.

Suffice to say, everyone was wrong. The first indication came when an L.A. grindhouse theater put on a limited double-bill of 1931’s Dracula and Frankenstein, opening to unexpected sold-out crowds who were ravenous to see the films that had so frightened the populace seven years earlier. Universal, paying close attention to what was unfolding, began a national re-release of a Dracula/Frankenstein double bill, and the rest is history. The films did tremendous business, their pop cultural stature having only grown during the years when they were more or less unavailable—keep in mind that this is long before the era of freely available home film screening. Audiences turned out in droves to see the classic monsters, which in turn jump-started Universal’s plans for a triumphant return of Frankenstein’s monster in 1939.

Here in 1938, however, the pickings are extremely slim. There are a handful of crime films or thrillers that border on horror territory, but little that really qualifies in a literal way. The year can at least claim to be home to one of the most notorious of lost monster movies: The Japanese King Kong Appears in Edo, which appears to have been simply ripping off the “Kong” name in order to tell a strange story about a trained ape kidnapping a young girl. Decades later, the supposed content of King Kong Appears in Edo is still hotly debated among kaiju film aficionados, with a lack of agreement on almost everything, including whether the ape in the film was actually a giant. Conflicting reports and confusing, surviving production stills are all that seem to be left, which is par for the course when it comes to the lack of content in 1938.

1938 Honorable Mentions: The Terror, King Kong Appears in Edo, Kaibyô nazo no shamisen

The Film: J’accuse!

Director: Abel Gance

Anti-war films don’t get much more devastatingly, soul-baringly earnest than Abel Gance’s J’accuse!/I Accuse!, which commits with over-the-top intensity to its single-minded mission to turn the hearts and minds of the proletariat toward pacifism. Arriving in French theaters a year before the outbreak of World War II, it presages much of the coming conflict, even as it reflects with horror upon the still-fresh wounds of the first World War. For director Gance, it’s clear that the previous 20 years have done nothing to dull the outrage he feels toward those who allowed the war to happen at all.

This version of J’accuse! can alternatingly be referred to as either a remake or a reimagining of Gance’s own, better-known silent version of the same story from 1919, also titled J’accuse!. As in the original, it’s the story of two French men serving on the front in WWI, simultaneously embroiled in love affairs with the same woman. This makes the film sound more like a romantic melodrama in its first act, but it then transitions into a harrowing portrait of idealist mania in the 20 years following the war. The survivor, Jean Diaz, leaves the battlefield with a solemn vow: To prevent another such war from ever happening again, largely through sheer force of will. As he becomes increasingly unhinged in his castigation of society, delivering soliloquy after soliloquy on such topics as the need for love over victory, he comes to believe he is somehow spiritually empowered to save humanity from itself. As the mouthpiece of the director, Gance apparently thought much the same, seemingly naive though his hopes may have been.

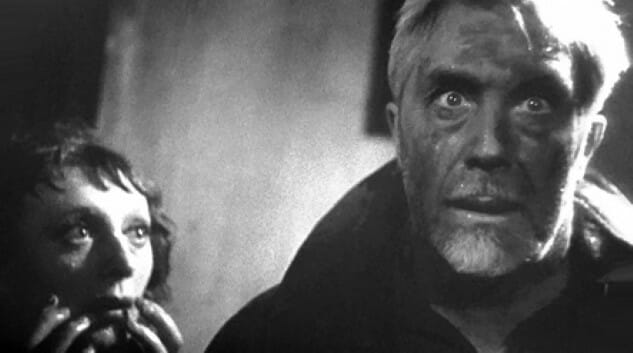

In terms of horror bonafides, this version of J’accuse! stands out in two areas. First is in its depiction of death and hopeless futility on the battlefield, seemingly taking inspiration from Universal’s All Quiet on the Western Front and laying some groundwork for Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. And then of course there’s the genuinely disturbing ending, in which the spirits of the dead slain in the first World War seem to rise from their graves, shambling back into service like Romero’s ghouls, 30 years before Night of the Living Dead. This sequence ends with the showcasing of actual, disfigured former soldiers of the Great War, which is difficult to look at even today. Naturally, it calls into question the nature of exploitation vs. unflinching responsibility to confront the horrors of the past, but it’s guaranteed to leave any audience feeling uneasy, regardless of their opinion on its ethics.

There are film fans who point to this J’accuse! as a lesser product than its silent, 1919 predecessor, but the presence of prolific French actor Victor Francen gives it an emotional identity that stands distinct from Gance’s earlier effort. His wild-eyed pontifications on the futility of war may strike a modern audience as somewhat self-aggrandizing, but it’s difficult not to be drawn under Jean Diaz’s spell, all the same. Just try not to feel a little guilt, when he points in your direction and says J’accuse!

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident horror guru. You can follow him on Twitter for more film and TV writing.