This post is part of Paste’s Century of Terror project, a countdown of the 100 best horror films of the last 100 years, culminating on Halloween. You can see the full list in the master document, which will collect each year’s individual film entry as it is posted.

The Year

We’ve entered the late 1950s, and the total volume of horror films being produced has gone into overdrive. The sci-fi/horror crossover is still going strong, with wave after wave of (rather cookie-cutter) giant monster movies such as The Deadly Mantis, The Amazing Colossal Man (more MST3K alums) and The Giant Claw, but this year also sees one of the pinnacles of the genre in the form of The Incredible Shrinking Man. Indeed, this era represents one of the peaks for science fiction as a populist film genre in general, coinciding as it did with the launch of the Sputnik satellite and the start of the space race.

At the same time, though, a noticeable evolution is making its presence felt in the horror genre: The rebirth of classical gothic horror, after a period of dormancy. You can see it in the film titles this year, which feature (around the globe) multiple vampire films, multiple “Frankenstein” films and I Was a Teenage Werewolf, to boot. Something is in the water, and the archetypes established via the Universal monsters are starting to come back into vogue.

Chief among the revivalists is a company whose name will appear steadily in these entries for the next decade, and then some: Britain’s Hammer Film Productions. Beginning with this year’s Curse of Frankenstein, the company would launch a gloriously colorized series of classical, gothic monster movies, reawakening old terrors associated with characters such as Frankenstein’s Monster, Dracula, mummies and werewolves, now presented in the lurid new tones of Eastmancolor, where pulses of bright arterial blood became the gruesome new standard. Benefitting from atmospheric set pieces and stylish direction by the likes of Terence Fisher, the newly christened concept of “Hammer Horror” would launch a new wave of imitators throughout Europe (especially Italy) and the U.S.A., proving that the horror genre didn’t necessarily need to lean on science fiction in order to be successful.

It was The Curse of Frankenstein that led the way, a film that was very difficult to keep out of the top spot for 1957—but fear not, as Hammer will be well represented in subsequent years. Starring the duo of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, who would become the two faces most associated with Hammer Horror productions, the film reevaluates the legacy of Universal’s Frankenstein films by cleverly shifting its focus away from the monster and onto the doctor himself. Whereas the Universal Dr. Frankenstein portrayed by Colin Clive, or his sons portrayed by Basil Rathbone and Cedric Hardwicke are all characterized as well-intentioned scientists who get swept up in the heady thrill of discovery and don’t realize their faults until it’s too late, Cushing’s Frankenstein is an imperious cad, through and through. A brilliant but egotistical rake, this Frankenstein doesn’t hesitate to resort to dirty tactics or outright murder to get what he wants, believing that the importance of his prospective discoveries will mean that the ends will justify whatever means he chooses to employ. In order to bring his creation to life, he’ll put friends and family into danger time and time again, making it clear that although Lee’s monster is hideous to behold, it’s clearly Dr. Frankenstein who is the film’s villain—traits that would be inherited by other film characters such as Re-Animator’s Herbert West, some 30 years later. The film would go on to inspire a bevy of sequels, in which Dr. Frankenstein gradually becomes something of an anti-hero, descending ever deeper into his desperation to perfect his scientific breakthrough.

1957 Honorable Mentions: The Curse of Frankenstein, Night of the Demon, Quatermass 2, 20 Million Miles to Earth, The Deadly Mantis, Lust of the Vampire, The Amazing Colossal Man

The Film: The Incredible Shrinking Man

Director: Jack Arnold

A pinnacle achievement in 1950s special effects and the concept of the science fiction horror-thriller in general, The Incredible Shrinking Man was the magnum opus of director Jack Arnold, who largely produced workmanlike science fiction films throughout the decade, such as It Came From Outer Space or Tarantula, although he also directed Universal’s Creature From the Black Lagoon. It’s The Incredible Shrinking Man, though, that stands the test of time as the most pure (and still quite entertaining) expression of the era’s populist science fiction tropes.

Our protagonist is Scott Carey (Grant Williams), an average, red-blooded American male on vacation with his wife when a chance exposure to radioactive materials (curse you, decaying nuclei!) begins a barely perceptible shrinking process. At first, it’s almost as if Scott is being gaslighted by the whole world, being told repeatedly that he’s never been 6’1’’, and must always have been 5’11’’—his insistence that he knows what he’s talking about seems reflective of the governmental paranoia of the age, as the citizenry was repeatedly being instructed by their own leaders to look away from the very real, daily threat of thermonuclear obliteration. Of course, the scientists can only give Scott the runaround for so long, though—eventually it becomes clear that Scott is indeed slowly shrinking, making his case into national tabloid news, and fracturing his relationships in the process. There are some nice visual illustrations of the crumbling marriage; in particular the scene where Scott’s wedding ring slips off with a clang, his hand having grown too small to support it. Scott responds with manic swings between cruel bitterness, suicidal ideation and desperate, unrealistic hope for divine scientific intervention. But as time passes, the thought of rescue slips further and further into fantasy, and Scott’s daily challenges begin to become more and more dangerous.

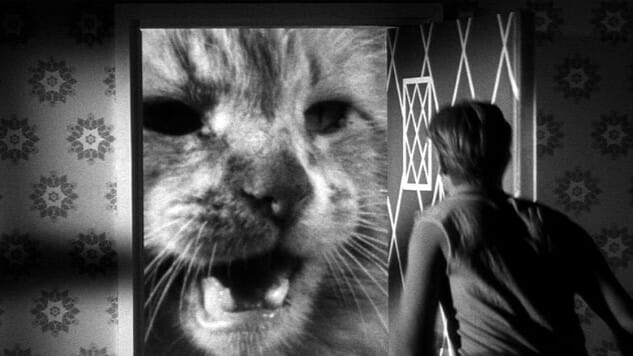

At a tidy 81 minutes, The Incredible Shrinking Man is an uncomplicated, high-concept story that cuts to the chase with immediacy. But for the nuclear-age flavoring, it’s a story that easily could have sprung from the pages of Lovecraft-era Weird Tales or Amazing Stories magazines, or the men’s magazines of the day, which so delighted in tales of man vs. beast in the remote wilderness of savage places. This film, on the other hand, simply transplants that story to the confines of an American household, subbing in a housecat for lions, or a monstrous, giant spider for some red-mawed beast faced in the depths of the jungle. It’s a simple but effective way of making the audience consider the nature of perspective, and how any given situation is often more subjective than we make it out to be—it just depends on your point of view. As a six foot man, a house cat is a loving little creature that depends on you for its every need. As a six inch man, it’s an alpha predator with every intention of first playing with you before it ends your suffering.

Many films had done “miniature person” FX before The Incredible Shrinking Man, but this one fully commits to the gimmick, and the results are quite impressive, if not always entirely consistent. You have to chuckle about some of the logistics—where are they getting these perfectly functional, doll-sized clothing, couches, beds and coffee tables? Why does a coffee cup look like a huge soup bowl in the hands of Scott, when he’s still supposed to be three feet tall? Once his shrinking has reduced him to the size of an insect, though, and he becomes trapped in the house’s cellar, that’s when Scott’s world becomes truly nightmarish—an alien landscape that he must thrillingly navigate through sheer ingenuity and derring-do. Simply watching him attempt to scale a shelf is a wonderfully suspenseful sequence, knowing that any slip-up could cost him his life.

Ultimately, The Incredible Shrinking Man makes for excellent populist entertainment, with some last-minute waxing philosophical, in the tradition of most sci-fi of the era. It’s mostly silliness, but the final lines are unexpectedly profound, ranking up there with The Thing From Another World’s “Keep watching the skies!” As Scott concludes, no longer afraid of the unknown as he continues to shrink into a new sub-atomic world: “Even smaller than the smallest; I meant something too. To God, there is no zero. I still exist!”

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident horror guru. You can follow him on Twitter for more film and TV writing.