This post is part of Paste’s Century of Terror project, a countdown of the 100 best horror films of the last 100 years, culminating on Halloween. You can see the full list in the master document, which will collect each year’s individual film entry as it is posted.

Unlike every other post I’ve written for this ongoing, 100-day Century of Terror project, this one isn’t dedicated to a specific year. Rather, this post is simply intended to offer a bit deeper exploration of the two weakest stretches in the history of the horror genre in the U.S. and abroad—the two periods when horror cinema almost seemed to have disappeared entirely. I’ll do my best to examine the root causes of why horror became so dormant in each time frame, and what ultimately led to its resurrection in each instance.

First up, the late 1930s.

1936-1938

It’s strange to think that horror ended up in such a trough, a mere five years after 1931 was likely the biggest and most influential year in the history of the genre. Dracula and Frankenstein had been box office smashes at Universal, and in the next few years they followed up with other foundational monster entries like The Mummy, The Invisible Man and Bride of Frankenstein. So too did other studios jump on board the horror bandwagon, enjoying the genre’s profitability in the early days of the sound era. But then, in between 1936 and 1937, things quickly dried up. In particular, 1937 and 1938 have almost no U.S. horror content at all, and international output is quite low as well.

Unlike the second trough, in the 1940s, it’s not too difficult to point to some causes here—although they’re sometimes misreported, the result of decades-old incorrect information that has apparently made its way into some texts and “common knowledge” of the era. Such are the difficulties of trying to understand the mindsets of Hollywood producers, more than 80 years ago.

The first factor that undeniably played a part in the dip, and can’t go without some degree of acknowledgement, was the sudden enforcement of the existing Motion Picture Production Code in 1934. The Code, also referred to as the “Hays Code” for Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), had existed as a self-policing measure for the industry since 1930, when it was established to mollify viewers who were angry about the perceived moral turpitude of the U.S. film industry and its stars, and prevent the federal government from stepping in with some form of official censorship. It was meant to provide an easily referenced list of actions, themes and depictions that were and were not deemed acceptable content, but actual enforcement of the Hays Code’s tenants had been practically nonexistent in its early years.

That all changed in 1934, as Joseph I. Breen became the head of the newly created Production Code Administration, an arm of the MPPDA that focused exclusively on enforcing the existing code. Practically overnight, the entire filmmaking landscape was thrown into disarray, as all films were now required to obtain a certificate of approval prior to release. It was the sudden establishment of a new normal that would persist for the better part of three decades, handing Breen an inordinate amount of power in the process. And as it will probably not shock you to learn—the guy didn’t exactly like horror movies.

1936’s Devil Doll was essentially rewritten from the ground up, thanks to the meddling of the PCA office.

1936’s Devil Doll was essentially rewritten from the ground up, thanks to the meddling of the PCA office.

As head of the PCA, the rigidly Catholic and serious-minded Breen seemed to see himself as not only the new sheriff of Hollywood content, but a primary force in influencing what kinds of films got made in the first place. Any genre whose content ran up against the rules of the Hays Code was likely to incur an arduous series of revisions and cuts, which immediately threatened the ease of production when it came to crime/gangster or horror films in particular. Given that the Code warned against such things as depictions of “brutality and possible gruesomeness,” the horror genre was being stripped of its bread and butter. Breen reportedly though that the horror genre itself was inherently immoral, and was thus willing to go far out of his way to discourage it.

And yet, horror films did continue to be produced, at least for a while, by studios that were willing to work within the boundaries of what they could get past the PCA. The Code started to be enforced seriously in 1934, but it’s not until 1935-1936 that the lack of horror cinema really becomes apparent. That’s when the so-called “British horror ban” went into effect, although the truth here is decidedly more complicated.

In reality, although you’re likely to see reference to a “ban on horror movies” existing in the U.K. at this time in various internet articles, the truth seems to be that the so-called “ban” was more of an elaborate campaign of misinformation, spread by Breen’s office. Although it is true that the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) professed to be hostile to foreign horror films, and instituted some tighter rating regulations in the early 1930s, their ratings were very inconsistent, and by no means did they ever institute a ban or a virtual ban, even for films rated “H” for “horrific,” which could still easily be viewed by almost all audiences. Breen’s office, on the other hand, played up the “ban” in the U.K. as much as it could, telling the American press and Hollywood studios not to bother producing horror films, as they’d be losing out on the important U.K. film market, where those films would be rejected or cut so badly that they’d become inevitable financial failures. At the same time, even when horror scripts were submitted for PCA approval, the notes and approval process was made so arduous that many never emerged from development hell. Ultimately, Breen’s campaign to dissuade horror production and conjure up the idea of a “ban” in the U.K. was so successful that it just became accepted fact for a period of time. You can see it in the following Associated Press headline from 1935: “Horror Films Taboo in Britain; The Raven Last.”

There were other aspects to the late 1930s decline, such as the change in ownership of Universal from Carl Laemmle to Charles Rogers and the Standard Capitol Corporation, but taken as a whole, they reduced the genre to practical nonexistence in the U.S., only a few years after it was the country’s most consistently profitable style of film.

The roots of salvation came in 1938, in a story that has also passed into legend at this point. As the story goes, in August of 1938, a theater owner in Hollywood named Emil Ullman was facing bankruptcy, and decided to pull out all the stops and go for broke to offer something different from his competitors. Acquiring some old prints of Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein, along with RKO’s Son of Kong, Ulmann programmed the horror genre’s first triple feature of all three films, advertising that “We dare you to see them together.” The promotion was incredibly successful—so successful, in fact, that Universal noticed all the attention its old monster movies were receiving in Hollywood and decided to embark on a nationwide double bill re-release of Dracula and Frankenstein in 1938. This release too was an incredible success, with some cities turning out higher box office figures for the films than they had in their initial release in 1931. The truth was made clear: Despite all the hand-wringing, the public hadn’t turned its back on horror cinema. Rather, they were ravenous for it.

That was all Universal needed to see in order to green-light production of 1939’s triumphant Son of Frankenstein, the film that would begin the genre’s Hollywood rebirth. Joseph Breen could protest all he wanted to specific bits of content, but Universal was intent on seeing the project through. It released everywhere to big box office and audience acclaim—including in Britain.

Horror was back, although it would face another lull in the late 1940s.

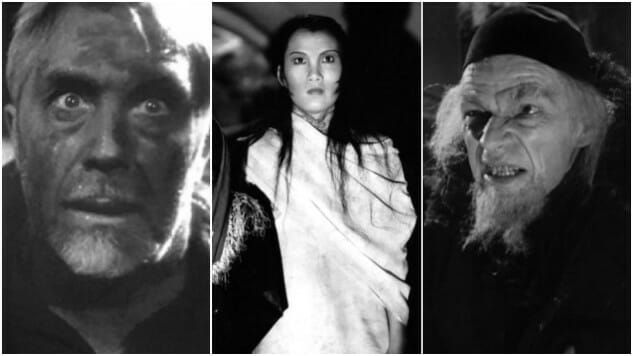

Karloff, Lugosi and Basil Rathbone revive the genre in Son of Frankenstein.

Karloff, Lugosi and Basil Rathbone revive the genre in Son of Frankenstein.

1947-1952

Whereas the horror trough of the late 1930s has some very concrete culprits you can single out, the more prolonged (but less total) dip of the late 1940s and early 1950s seems to have come about in a significantly more organic way. There isn’t a specific bogeyman to point to here, like Joseph Breen’s PCA at the height of its powers in the 1930s. Indeed, Breen was still at it in the 1940s, although the ability of the PCA to bully studios into drastic revisions had weakened somewhat, and would continue to weaken into relative obscurity by the 1950s. The reasons for the horror dip here seem a bit more subtle than they were a decade earlier.

One of the most commonly cited reasons is a general, vague notion that theater audiences, having lived through the horrors of observing World War II in film strips and splashed across the front pages of newspapers, had simply soured on the genre as a response to a world with too many horrors in it. This hardly seems to make a lot of sense, though, given that some of the genre’s biggest boom years of the 1940s were during the height of the American military’s involvement in Europe and the Pacific. Would audiences really have turned to horror films as a form of distraction during the war, but suddenly have found them distasteful after the war?

What seems more realistic, observing the landscape of horror releases, is that the genre simply became rather staid over time. Simply put, there was a whole lot of repetition in the horror genre in the 1940s, as monster movies, “old dark house” films and “mad doctor” premises ruled the day and were repeated ad nauseam, with very little variation, outside of innovators like Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur at RKO. At the same time, the film noir genre had coalesced into something recognizable, and may have been stealing some of horror’s thunder, transplanting the same dark, scary or moody energy into a new style of films that felt more adult, risque or sexy to audiences. At the same time, the career fortunes and visibility of the previous generation of horror stars, from Karloff and Lugosi to Peter Lorre, reached some of their lowest points. The lingering effects of post-war xenophobia may have played a part here, especially in the cases of Lugosi and Lorre—both Hungarian born, but associated with German cinema before they emigrated to the United States.

Films like Lewton/Tourneur’s Cat People were bright spots in a field that could often feel same-y in the early to mid-1940s.

Films like Lewton/Tourneur’s Cat People were bright spots in a field that could often feel same-y in the early to mid-1940s.

The effects, regardless, were a slow weaning and die-out of the style of horror film that was synonymous with the genre at the time. Beginning in 1946, and continuing into the end of the decade, Universal essentially closed shop on its classical monster movies, waving a fond goodbye in 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein to Dracula, the Wolf Man and Frankenstein’s Monster. Years like 1947, 1949 and 1950 have almost no U.S. output that can be properly labeled as horror, and are salvaged only by international films such as Britain’s The Queen of Spades in 1949. In the U.S., horror films have been replaced almost entirely with movies that are instead noir and noir-adjacent, and the horror films from earlier in the decade must have looked very old-fashioned indeed. 1950 feels like rock bottom for the genre: The least socially relevant that horror movies had ever been in the U.S. since the early 1920s.

It’s fitting, then, that this time around the genre is saved not by rediscovery of the old classics but by fusion with a new and upcoming genre that was fresh and sparkly in the public eye: science fiction. If there’s one thing I can believe about the changed tastes of post-war American theater-goers, it’s that they likely wanted to see stories that seemed more “modern” and relevant to the dawning of the nuclear age, and science fiction ably filled those requirements. Films such as The Thing From Another World and The Man From Planet X in 1951 were early entries in portraying alien invaders as a new cinematic villain du jour; a trend that would be fleshed out more fully in movies such as The Day the Earth Stood Still, Earth vs. The Flying Saucers, War of the Worlds and It Came from Outer Space. At the same time, Vince Price’s House of Wax in 1953 gave some new life to the more classical side of the horror genre by latching itself onto another modern presentation gimmick: 3D. All in all, the stage was set for the horror revival of the 1950s, which would first take the form of giant, irradiated monster movies (Them!, Tarantula, The Deadly Mantis, etc), before Britain’s Hammer Film Productions gave colorful new life to the Dracula and Frankenstein mythos’ at the decade’s end.

The horror genre eventually found its salvation in the waiting arms of science fiction like The Thing From Another World, before distinguishing itself once again by the end of the 1950s.

The horror genre eventually found its salvation in the waiting arms of science fiction like The Thing From Another World, before distinguishing itself once again by the end of the 1950s.

In the decades since, the horror genre has of course seen more ups and downs, but never has it experienced a true drought like it did in 1936-1938, or 1947-1952. These days, with the box office performance of the genre at roughly the strongest it’s ever been, the future still seems bright for cinematic chillers.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident horror guru. You can follow him on Twitter for more film and TV writing.