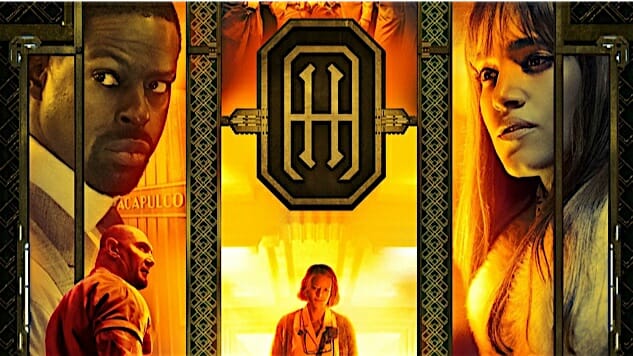

What Exactly Was Wrong with Hotel Artemis?

Dissecting the trend of candy-colored shooters

I have a confession to make: I have no use for guns, but I freaking love shootout movies, and the more transparently absurd the better.

It’s never difficult to figure out why a movie that’s merely a cheap rip-off of other successful movies is bad or had a tough time at the box office. Every now and then, though, you get a curiosity like Hotel Artemis, which has just enough original ideas and ambitious world-building to register as something memorable, yet whose failure so clearly illuminates the rules of the genre that spawned it.

It’s interesting to find the various sources of Artemis’ DNA—taut tales of assassins who are on their way out the door only to feel the sensation of a target on their backs—date to at least two 1967 classics: the Japanese pot-boiler Branded To Kill and Jean-Pierre Melville’s inimitable Le Samouraï. Movies as early as John Carpenter’s Assault On Precinct 13 place combatants in a discrete space before unleashing the squibs. (Call it a “gunfight cozy” maybe?) You can even see some Die Hard and its various lackluster imitators injecting the cinema landscape with recognizable and easily distinguishable baddies, in contrast to the poor faceless fools who fill out the ranks of thugs in most forgettable actioners. Tarantino, and his various precursors and inspirations, give us killers as nonchalant in a firefight as they are around the table with their fellow cutthroats. And of course, John Woo introduced the world to gravity and logic-defying gunfights in movies like Hard Boiled.

But what typifies Hotel Artemis’ particular genre for me right now is—and this may sound simplistic—the color. Action films of yesteryear tended to be grimy and low-contrast, and the disciples of the Jason Bourne movies of the early ’00s decided that frenetic and choppy camera movement and editing made for edge-of-your-seat action (rather than merely kinetosis). Contrast that with the current crop of avowedly saturated movies, in color, in clarity of photography, and in personality. Call it the candy-colored shooter—bright, quirky characters engaged in nothing more complex than a rip-roaring shootout, inaugurated in its entirety, perhaps, by 2006’s Smokin’ Aces. Sometimes that combination sticks the three-point landing. Other times, as with Hotel Artemis, it stumbles: The modest $15 million film has barely brought in half its budget.

So, what have been the hallmarks of its more successful fellows? And why did this curious specimen fail to catch that same lightning in a bottle?

A Little Less Conversation, a Little More Action

Speaking of Smokin’ Aces, I can’t think of a better analog to Artemis 11 years later, though it was by far a worse movie for a few key reasons, starting with its overly convoluted plot.

Generally, I find the better entries of this slim genre don’t mess around with complications: Baby Driver and Driver were both permutations on it and neither left you wondering at motivations, revelations or plot twists. Aces and one of the other movies I consider to be the forebear of these shooters, The Way of the Gun, were so in love with the sound of their own voices that they couldn’t shut up for a second and let us focus on the action. Aces in particular went the same route as Hotel Artemis in bringing an A-list team (Andy Garcia, Ben Affleck, Ray Liotta, and some guy who starred on some show called Entourage, I think?), and in trying to keep the stakes brutally simple—somebody must be protected from somebody else who wants them dead.

Then Smokin’ Aces gets into its supposedly clever backstory and you realize it is a garbled mess you aren’t interested in following, and which doesn’t add any compelling context to scenes like, for instance, two guys feeding each other a ten-course meal of lead in a cramped elevator.

Contrast this with a movie like John Wick, which might be this genre’s pinnacle so far and yet which sounds hilariously dumb on paper. You know by now that the plot revolves around the idea that Wick (Keanu Reeves) is on a roaring rampage of revenge because some thugs killed his dog in the midst of stealing his nice car. It’s precisely that simplicity that allows directors (and former stuntmen) Chad Stahelski and David Leitch to put all the focus on the few scenes of weighty emotion necessary to get to the heart of the characters, then go full steam ahead into dazzlingly shot action sequences.